CHICAGO -- Nayeli Manzano, a 16-year-old undocumented immigrant, woke at midnight Wednesday after about an hour of sleep. A friend had called, saying a large crowd was gathering on Chicago's Navy Pier.

Manzano wanted to be among the first in line for an event that would help thousands of young undocumented immigrants apply for work authorization and reprieve from deportation under a new Obama administration policy. Wednesday was the first day to apply. The event at Navy Pier, and others like it, ensured thousands would.

"This is my chance, I'm not going to let it go," said Manzano, who wears black-rimmed glasses and sounds older than she is. "I'm the right age, I haven't done anything wrong, I don't have a criminal record. I am a good student. So I told my parents, [Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights] is going to have an event, and I want to be one of the first ones to be there."

Manzano had planned to take the El train with her parents to the pier around 4:30 a.m. The line would have been hours longer by then. At 6 a.m., organizers at the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights blasted out an email saying more than a thousand people were in line. By 7 a.m, there were more than 2,200 in a line snaking through hallways in the Navy Pier event center and down the pier, past a charter yacht and a Ferris wheel and south along Lake Michigan.

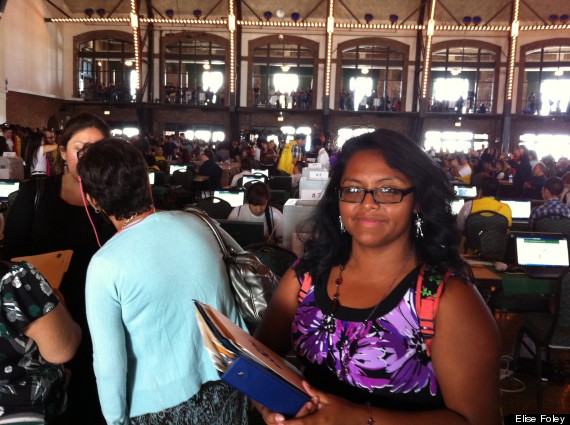

Nayeli Manzano, 16, waits in line to submit her application for deferred action at Navy Pier in Chicago.

By 1 p.m., organizers estimated that 13,000 people had come to Navy Pier for the event, making it the biggest deferred action gathering in the U.S. on Wednesday. The earliest applicants arrived at 6 p.m. Tuesday and slept there, some carrying sleeping bags with them on Wednesday. Others brought board games, laptop computers or knitting projects. But most passed the time by talking to those around them about plans, once they're approved -- they hope -- and able to work, attend school and drive without fear of deportation.

Manzano and her parents arrived at Navy Pier in the middle of the night, around 2:30 a.m. Manzano, one of 800 event volunteers, got to work immediately, donning a yellow Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights vest over her purple dress and walking the halls, helping fellow attendees organize their application documents. Her father, who immigrated from Mexico a few years before the rest of the family, held her place in line. Her mother, who crossed the border illegally with Manzano when her daughter was 4, rested in the car.

The Obama administration announced June 15 it would stop deporting many young undocumented immigrants, mostly following the lines of the Dream Act, a decade-old bill that came within five votes of passage in the Senate in 2010. The bill has gone nowhere since, and Obama, frustrated with the lack of progress and facing a Latino electorate increasingly frustrated with him for a record number of deportations, took the matter into his own hands with a directive to give deferred action and work authorization to some undocumented young people. It may have been a political move, but among all of the chatter about who's up and who's down, it shows how a policy can matter beyond an election: from the 13,000 people at Navy Pier on Wednesday to the 1.7 million estimated to be eligible nationwide.

The administration has promised it will hire enough staff to handle the influx of applications. Still, long wait times are expected, especially with high turnout at events around the country like this one. Groups held similar events in New York, the District of Columbia, Los Angeles and Detroit, among other cities.

The hundreds of volunteers at the half-dome-shaped grand ballroom at Navy Pier included 60 lawyers, but the process moved slowly. Manzano made it into the ballroom around 9 a.m. and went through a series of tables, where she showed documents and answered questions about whether she has a criminal record and whether she meets other requirements. She finally made it through the process around 2 p.m. Many others were still waiting. Closer to the end of the line, volunteers gave mini-sessions to those who wouldn't make it to the front by the end of the event, giving them information about future events. Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and Rep. Luis Gutierrez (D-Ill.), the biggest champions of the Dream Act in Congress, walked through the crowd to offer support.

Attendees were instructed to bring documents showing their age and identity, proving they came to the U.S. more than five years ago and before they turned 16. They also need to show that they are either in high school, graduated, or obtained a GED, or that they were honorably discharged from the military. Immigrants were also told to bring $465 to pay for the application to the government, meant to cover the cost of processing. The administration has said applications will not lead to detention or deportation except in rare cases, and most seemed to trust that they were not putting themselves in the hands of a government that would then use the information to deport them.

Still, the policy is a temporary one, and could be ended at any time. It's a tricky issue for presumptive GOP nominee Mitt Romney, who admitted at a National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials the week after Obama's announcement that he would have preferred not to talk about immigration. Romney said during the Republican primary that he would veto the Dream Act, and has said he opposes Obama's action. He hasn't gone so far to condemn it as amnesty, though, and has refused to say whether he would end it if he's elected.

Many advocates of the directive said they don't think Romney would do something so unpopular as reverse it, although they don't want to give him the chance. Most Republicans stayed clear of the issue on Wednesday. Only one prominent Republican, immigrant hawk Rep. Steve King (R-Iowa), put out a statement criticizing the policy. Luis Tellez, a 19-year-old would-be Marine with a buzzed haircut and a camo-print backpack, said he thinks the Dream Act will eventually pass. "Politicians are looking at the political aspect of it, and it's not only good for them but it's good for the country," he said.

Polling indicates that hard opposition to deferred action may be a bad idea for politicians. Like the Dream Act, deferred action is popular, and aid for young undocumented people is less polarizing than helping older immigrants who came on their own accord.

Undocumented young people at Wednesday's event said they mostly want to work legally or obtain a driver's license so they can get around. Many hope to use that work authorization to pay their way through college or to begin saving. For Ilian Claudio, 19, deferred action would mean going to college. She came to Navy Pier around 4:30 a.m. with her friend Jahayra Martinez, 20, and Martinez's father and sister. She and Martinez have been friends since high school and have similar stories: both were born in Mexico, both came to the U.S. illegally to join their parents as children -- Claudio was 13, Martinez was 12 -- and both are now working. "It's a historic day, I want to be part of it," Claudio said.

That's why she and others said they came on Day One of the application process, braving the long lines and early wake-up calls.

"It's a new beginning," Claudio said. "It's like that gate opens."