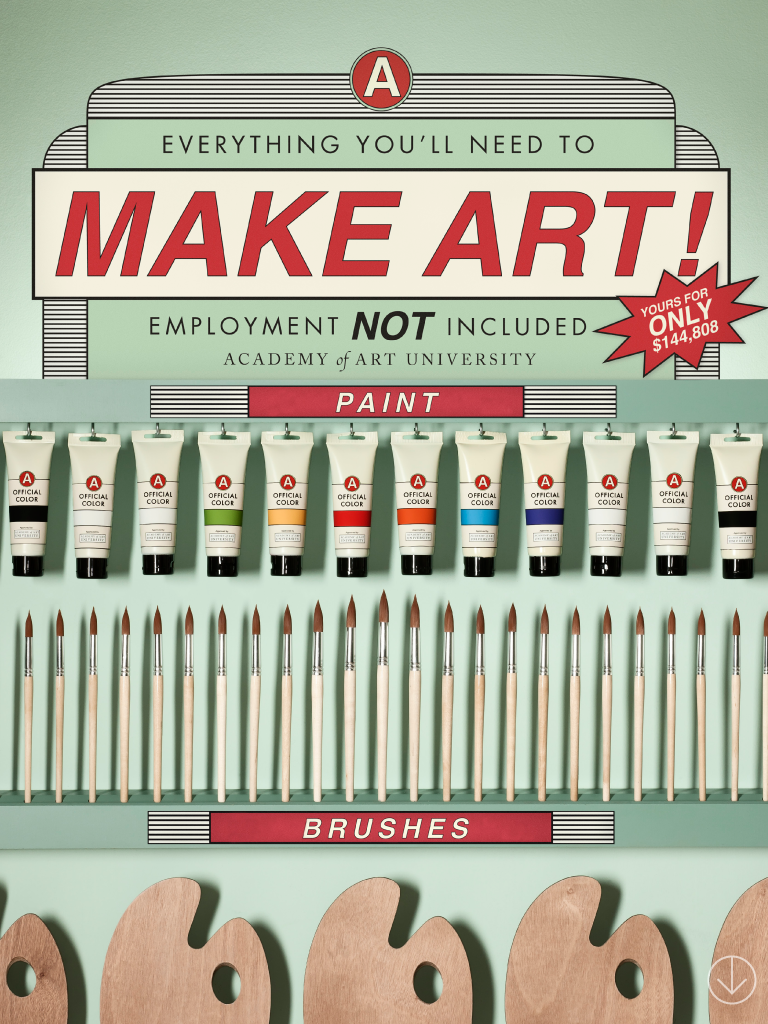

(Photo Illustration by Dan Winters)

A half-empty shuttle bus rolls down a crowded street in San Francisco. A tattooed 20-something art student steps off and lights a cigarette. She walks past a bus station, under a flag affixed to a streetlight and into an unremarkable downtown building.

Everything in this picture -- from the side of the bus, to the emblem stitched onto her backpack, to the advertisement on the back of the bus stop, to the flag flying above her head, to the awning above the building she just stepped into -- bears the same logo.

A crisp, stylized double "A" surrounded by a bright red circle, visible from almost every downtown corner, marks the ever-expanding footprint of the Academy of Art University. The private, for-profit college has become, over the past century, the largest arts school in the country and one of the biggest landholders in San Francisco -- only the Catholic Church owns more buildings.

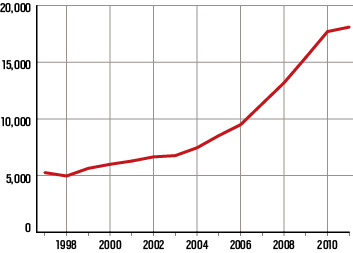

In the past two decades, the Academy of Art has grown 10 times in size to nearly 20,000 students. And administrators are pushing for more: a recent school master plan projects a student population of nearly 25,000 within five years, roughly the same number of undergraduates who attend the University of California at Berkeley. It is the only arts school in the nation with both NCAA basketball and baseball teams.

The university has opened recruiting offices in Taiwan, South Korea and Thailand. It's created a massive online division, aimed at beaming courses on classical sculpture and video game animation taught by teachers located as far away as Scotland to thousands of virtual students across the world.

As the Academy of Art has expanded, so has the local prestige of its owner, Elisa Stephens. The 52-year-old lawyer has become a fixture in San Francisco high society, and is a regular attendee at fundraisers thrown by the city's political and social elite. Her mansion sits atop Nob Hill, one of the city's most exclusive zip codes.

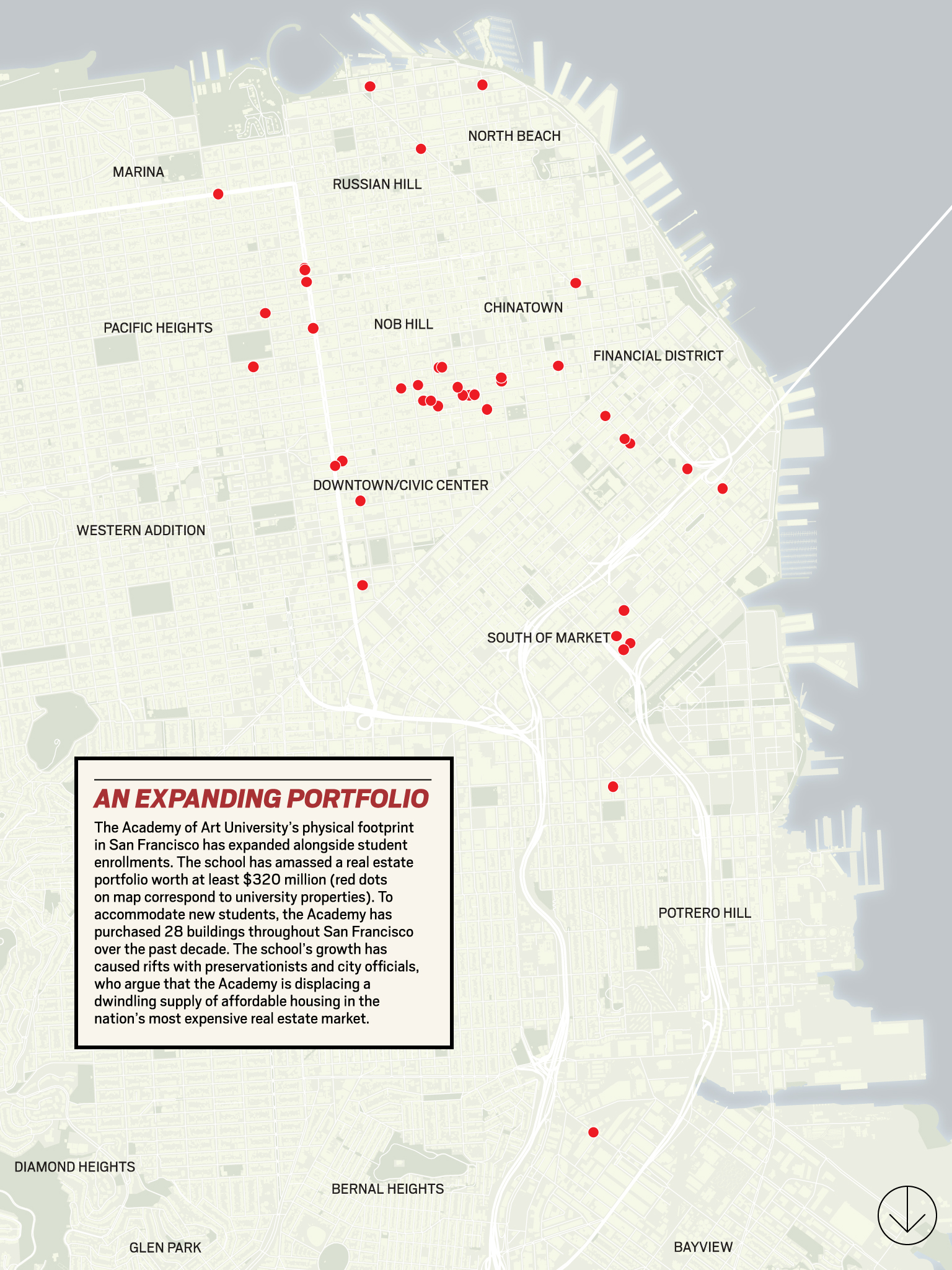

Under Stephens' leadership, the school has purchased dozens of properties across the city, amassing a real estate portfolio worth at least $320 million. Annual revenues in 2009-10 were more than $247 million, up from $59 million a decade before, according to the most recent federal data.

University officials did not make Stephens available for an interview after multiple requests, citing a busy schedule, but she responded to questions by e-mail. The university referred other questions to a spokeswoman, Susan Toland.

President of the Academy of Art, Elisa Stephens, addresses an audience at The Cannery in San Francisco. (Photo courtesy of Randy Brooke/WireImage)

"Academy of Art students are being hired by some of the most innovative companies in the world -- many of which are located right here in the Bay Area," Stephens notes. "We are preparing students for the jobs of the innovation economy and if they come in here committed to being successful, our program is the best in the world when it comes to art and design fields."

Stephens says the school's emphasis on technology in arts training gives the school opportunities to tailor curriculum to the demands of the workforce.

"With the endless possibilities technology brings, in 10 or 20 years we could have a handful of new majors that don't exist anywhere today," she says. "That is one of the things we are most proud of -- our ability to quickly adapt our offerings based on the latest industry trends -- and that will be true for as long as I am running the Academy."

Spokeswoman Susan Toland calls Stephens a "maverick" who has expanded the university to meet the desires of students looking for practical education.

"She wants to change the way we think about art education," Toland says of Stephens. "She wants the Academy of Art to be a top-tier school and realized there's so much demand out there for art education that wasn't being met."

Toland says the university's fast growth reflects a willingness to teach art to anyone who is interested, not just a privileged few.

"Most people haven't had the chance to develop a portfolio, especially if they don't have parents that can pay for art classes and can afford to take summers off to make art," she says. "The school is their opportunity to prove themselves."

Enrollment at the Academy of Art University has grown swiftly in recent years, more than doubling since 2005.

Still, the Academy's expansion has sparked bitter confrontations with city planners and slow-growth activists, who argue the school's real estate appetite is helping to exacerbate a citywide housing crunch, making San Francisco increasingly unaffordable for all but its wealthiest inhabitants.

"When you're growing with no end in sight, that's like a cancer, like a virus," former San Francisco Deputy Mayor Brad Paul says of the school's real estate empire.

The school's academic reputation is also at risk. California higher education officials recently blocked it from receiving state tuition grants, arguing that its recent graduation rate of less than 30 percent doesn't justify further public investment.

In addition, a group of former recruiters has filed suit against the school, claiming some of its student enrollment growth was the result of bonuses, raises and other enticements offered to recruiters if they met sales targets. Compensation schemes rewarding recruiters based on the number of students enrolled violate federal law. The Academy declined to comment on the matter.

"It seems to me that money is their number one priority," says Natalie Wilkey, who got a BA from the school's fashion merchandising program in 2010. "They're not about the community, it's more like they're a corporation."

For-profit colleges such as the Academy of Art have proliferated over the past decade, growing the number of student enrollments more than fivefold nationwide since 1999. They advertise heavily on subway cars, highway billboards and late-night television, often promoting degrees as a path to career advancement.

Such schools have increasingly caught the eye of federal regulators and state attorneys general, who have moved to crack down on institutions that promise more than they deliver, leaving students stuck in debt and without improved job prospects. Some of the largest players in the industry, including the University of Phoenix, have experienced enrollment declines over the past year as government regulations have tightened.

Unlike the for-profit system's many problem children, the Academy hasn't been charged by authorities with violating any laws, and many art and design professionals and students consider its curriculum top-drawer. Also, unlike many for-profit institutions that have sprung up almost overnight in recent years, the Academy of Art has a long tradition in San Francisco, with a history stretching back to the late 1920s.

The school's student loan default rate -- often an indicator of poor student performance after college -- is well below the national average, and far below the average default rates of other for-profit schools. Administrators cite statistics from last year showing an 80 percent job placement rate for graduates, though school officials say the measurement is preliminary because the U.S. Department of Education has not finalized the formula.

"Because we make sure every student learns the fundamentals, employers tell us they love hiring our grads," says Sue Rowley, the university's executive vice president of educational services. "They don't have to retrain our grads on basic skills."

In many ways, the Academy's profile and problems are more akin to the woes facing law schools, which also have been criticized for over-enrolling students who are then burdened with heavy loan debts and graduate into an intensely competitive and unforgiving job market.

As the Academy aims for continued expansion on the ground and online, former students and faculty have questioned how a university rooted in the creative arts will be able to follow through on promises of practical career training. Research has found that students graduating with degrees in the arts face some of the highest rates of unemployment among all recent college graduates.

This has created divided opinions about the Academy among its graduates. Some remain fans.

"There's people that rave about the school; and there's people who are really sharp critics of the place, the ones who think that it's this money-hungry art school," says Tommy Stracke, a recent 3D modeling graduate who is working for a startup gaming company in the Bay Area. "I think you make of it what you put in, really. There are people who have a passion for art but maybe aren't the most skilled. A lot of times they can get in, but then they just kind of find themselves in a stagnant state."

Others have walked away from their experience at the Academy with a harsher view.

"I think their ambition and their greed has fueled the rapid pace of growth," says Ryan Ballard, a New Orleans artist who recently graduated with a master's degree in sculpture from the Academy's online division. He says he regrets enrolling because he is no better off than before he entered and is saddled with more than $100,000 in debt. "They have quite possibly lost their soul in a lot of ways in the drive to make money."

FROM A LOFT TO AN EMPIRE

The massive university that now dominates downtown San Francisco got its start in a humble two-room loft in 1929. Richard S. Stephens had just returned to the West Coast with his young family after a stint in Paris trying to make it as a painter after World War I.

He took a job as art director for Sunset magazine, which had chronicled the natural splendor and gradual development of the American West, and in the evenings he decided to teach illustration on the side. He named his school the Academy of Advertising Art, starting with a class of five students.

At the time, there was a huge demand for professionally trained illustrators for the burgeoning publishing industry. As photographs began to supplant illustrations on magazine covers and on advertisements, the school launched a photography major in the 1940s.

When Richard S. Stephens gave control over the university to his son, Richard A. Stephens, in 1951, a scant 250 students attended. Over the next four decades, the second Stephens to hold the reins of the Academy gradually increased enrollment up to 2,300, adding courses for fashion design and film and music production.

As the school grew, so did the family's affluence. During his tenure, Richard A. built what became one of his most high-profile legacies: the Academy of Art's Automobile Museum.

Perched like a glass trophy case on one of the busiest corners of the city's main thoroughfare, the museum houses the Stephens family's collection of nearly 200 classic cars, including a 1954 Corvette and a 1930 Cadillac V16 Roadster. The structure is a testament to the family's vast private wealth, and almost everyone in San Francisco has stopped for at least a moment to ogle the automobiles.

By the time Richard A. handed the reins to his daughter, Elisa, in the early 1990s, the university was regarded as a sort of blue-collar training school for the arts, a class apart from highly regarded and highly selective programs such as the San Francisco Art Institute.

In a 1998 interview in the San Francisco Chronicle, Richard A., then Chairman of the Board, lamented the school's underdog status. "It's always confounded me that the Academy isn't more respected," he said at the time. "We are the best art school, probably in the world ... [But] there's a social prestige with the Art Institute. We don't have the prestige."

Much of that lack of respect in the local art world came from the school's policy of accepting virtually everyone who applied. Elisa found a way to turn that liability into an asset. Not requiring a portfolio as a prerequisite opened up enrollment to a much broader group of students than at other schools with rigorous admissions criteria.

"We've always had this very democratic philosophy, from when Richard Stephens was teaching ten students in a loft," explains Toland, the spokeswoman. "The Stephenses have always believed art skills are something you learn, not something you're born with."

Many students have been attracted to that model. "The main reason I decided to go was because they accept everyone," explains Wilkey, the Academy graduate. "I didn't want to jump through any hoops to get into college."

Under Elisa Stephens, the school's growth catapulted. Enrollment kicked into high gear, expanding at a much faster rate than before, according to federal data.

The growth has helped boost Stephens' local profile. Her guests of honor at the school's spring fashion show this year included Saudi Princess Her Royal Highness Reema Bandar Al-Saud, noted fashion director Sarah Burton, San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee and former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown.

"Nothing at the university happens without Elisa Stephens; no one there has authority other than her," says former Planning Commissioner Ron Miguel. "She and the institution are one and the same."

A BRANDED CITY

As the school's growth surged in the mid-1990s, so did its need for real estate. Administrators decided to start guaranteeing housing to all incoming students, which kicked off an ongoing buying spree.

Over the past decade, the Academy of Art has purchased 28 buildings throughout San Francisco, including landmarks such as St. Brigid's Church, one of the oldest structures in the city. University officials even tried to purchase the city's historic Flower Mart in 2007, a sale that would have displaced more than 30 businesses. Strong public outcry eventually squelched the deal.

The rapid pace at which the university gobbles up buildings and converts them for its own use has drawn the ire of many city officials, who point to a litany of planning code violations by the Academy, including a history of consistent failures to file master expansion plans and illegal conversions of residential buildings into student housing.

"If you or I committed these types of violations on this scale, we'd be dragged in front of a judge," said former Board of Supervisors President Aaron Peskin, who noted he received hundreds of complaints about the school from neighborhood groups concerned about evictions to displaced businesses to traffic congestion around university properties. "That's how it works for normal people, but not how it works for Elisa Stephens."

The Academy disagrees with these critiques. "The university has a healthy relationship with the city," says Rebecca Delgado, the school's vice president of community and government relations. "The city has a fundamental responsibility to make sure that the students remain in San Francisco because they contribute to the city both economically and culturally."

But others say that the Academy's wealth and influence allow it to simply plow ahead.

"They have a culture of do whatever you want first, and then ask questions later," adds Paul, the former deputy mayor. "They don't tell the city what they're going to do until after they do it, figuring they can just ignore the planning code...[The school] doesn't behave like a real estate developer, but that's really what it is."

Toland, the spokeswoman, disagrees with the assertion that the school has had carte blanche in the city. "We've been under scrutiny for a long time now," she says. "The city pays a lot of attention to what we're doing...In a lot of ways we're always the poster child."

In early 2010, the city's Board of Supervisors held a hearing on the university's myriad code violations, with supervisors and outside housing advocates decrying its real estate practices. "I've been here for ten years, and you've been a problem since I've been here," then-Supervisor Sophie Maxwell told Academy officials at the meeting, explaining that the school's flagrant skirting of city regulations reflected poorly on both the institution and the city itself.

In an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle at the time of the hearing, Elisa Stephens defended the school's real estate practices.

"We did not intentionally violate any laws," Stephens said. "We care about San Francisco -- the city and the community -- but there is lot of red tape. This is the city's reputation."

Stephens, in an e-mail, notes that the school is working to improve its relationship with the city.

"We are addressing these issues with the city because at the end of the day we think we share the same goals for this city -- to be the global innovation economy leader," she notes. "We truly believe that the relationship between (the university) and the city should be a win-win."

A report commissioned by the school in 2010 found that it directly and indirectly supports 4,600 jobs in the city and contributes $140 million annually to the regional economy.

The Academy also has an impact on San Francisco's fast-dwindling supply of affordable housing -- especially when it purchases rent-controlled apartments and converts them into dormitories.

Not only does San Francisco have both the highest average rent ($1,905 for a two-bedroom apartment) and highest median home price ($705,000) of any major city in the country, but those prices are increasing faster than anywhere else. San Francisco only covers about 49 square miles (less than the total acreage of Walt Disney World), making the city tiny and dense and also making construction of new, affordable housing difficult.

Tenants' rights advocates shake their heads at the Academy of Art's conversion of rent-controlled units. "Taking affordable housing off the market really bothers me because we need it for our own citizens," said Miguel, the former city planning commissioner. "It shows a blatant disregard for the city."

Earlier this year, San Francisco Supervisor Scott Wiener proposed legislation that would enact a city-wide prohibition on converting regular apartments to student housing and create a financial incentive for schools to build new facilities as opposed to taking over old ones. The Board of Supervisors passed his measure.

According to Delgado, the Academy executive, the city's famously onerous and bureaucratic development process makes it difficult to construct new properties as needed. She also says there's "no evidence that the school is displacing tenants."

The school does, however, appear open to the proposition of creating new facilities. "Anything is possible," Delgado says. "Once everything settles with this new law, we will take a look at building new housing."

DIALING FOR DOLLARS

The Academy of Art's real estate boom was a direct result of student demand. Thousands of budding artists were flooding into San Francisco each year, and everyone needed a place to live.

One possible factor for the Academy's rapid enrollment growth was suggested in a 2009 lawsuit filed by three former Academy of Art enrollment advisors. The suit alleged that Academy officials enticed its sales force to enroll legions of students by doling out Hawaiian vacations to top recruiters -- a practice prohibited by federal law.

Rewarding people for sales success makes sense in most industries, but it can lead to conflicts of interest in higher education. "It creates an incentive to enroll as many students as possible, without any thought to their ability to do the coursework," says attorney Stephen Jaffe, who is representing the plaintiffs in the suit.

Academy officials won't comment on the suit since it's still pending in court.

Earlier this year, California's infamously cash-strapped government looked to winnow down the cost of its Cal Grants program, which provides tuition assistance for college-bound Golden State residents. To better focus resources, the state raised the benchmarks for what a school needs to qualify for the money: a 30 percent graduation rate and a 15.5 percent loan default rate. Academy of Art was one of 154 schools that slipped below this threshold.

While the vast majority of schools disqualified from the program were cut for having unacceptably high student loan default rates, Academy of Art was one of a small handful that missed out because its graduation rate was too low. The university has sued the state, asking to be readmitted to the program because it has since upped its graduation rate from 29 percent to 34 percent.

"The Academy of Art does a good job of providing financial literacy for its students and keeping the number of defaults to a minimum," said Ed Emerson of the California Student Aid Commission. "But even a 34 percent graduation rate isn't something to really be proud of."

Toland says one reason the school's graduation rate may be low is that some students leave midway because they get job offers. "We grade ourselves on how many of our students get jobs," she says, "not how many get diplomas."

Academy of Art has long been concerned about its high dropout rate. About a decade ago, the school created the Student Advocate Advisor program to help incoming students navigate their first year-and-a-half at the school. "We were the new students' best buddies," said Emily Esch, who worked as one of those advisors from 2004 to 2006. "Our job was really about retention -- making sure the people who dropped out were doing it for the right reasons."

Many of the problems Esch encountered stemmed from a combination of the university's open admissions policy and a strong recruiting surge. "Sales team's goals were really, really aggressive," she said. "They were being pushed to get more and more students."

A former Academy of Art academic employee said the focus on retention was a business decision by the school, one that encouraged its faculty to lower academic standards so underperforming students would return for a second year.

"It wasn't about the quality of the portfolio packages. That was what you said in front of the cameras," says the former employee, who declined to be identified to avoid difficulties with his current employer. "Behind closed doors, when everybody is sweating and there are stains in everyone's armpits, it's all about the numbers. It was about keeping attrition down: How do we keep underperformers in the program, and how do we lower our standards to include more?"

One way the school includes more students is through heavy international recruitment practices. Academy of Art has offices in Taipei, Taiwan; Bangkok, Thailand; Seoul, South Korea; and a representative in India. University Facebook pages and the school's website advertise in at least four different languages, listing dates for meetups and information sessions.

According to the same former employee, international students serve as a huge source of revenue for the school. "The thing that's great about international students is not only are they full ride, but they have to take ESL classes, which are in addition to whatever their unit loads are," the employee said. "So not only do they nail them for the unit loads, but they take an additional three or five classes of ESL, which are full tuition price courses."

International students tend to represent a significantly more affluent segment of the population than the overall student body. "Money wasn't an issue for a lot of the international kids," recalls Esch, the former student advisor. "They had to pay cash up front and didn't get government loans."

Academy of Art has also managed to rapidly expand enrollments in recent years through its introduction of online-only degree programs. Almost all the university's majors, from painting to graphic design to visual effects, are available through fully online coursework -- a development that has raised concerns among both students and faculty about an erosion of quality in its programs.

"The push for that, to me, is 100 percent entirely due to the economic benefits of online education," says a second former employee, who also declined to be identified in order to preserve relationships with faculty members. "You create a class once, and you're done, and anybody can just teach it. The only beneficiary of that is the school itself, because of the profit potential."

Several former academic employees described the difference in quality between the work of online and on-campus students as vast. Artwork from online students very rarely makes it into the Academy of Art's annual spring show, which features the best student work of the year and is often a jumping-off point for job opportunities, the employees said.

Rowley, the university vice president, claims that online students participate in both the spring and fall shows. "We've gotten rave reviews from everyone who has seen our online programs -- teachers, accreditors, everybody. They've all given it five stars," she says. "With the explosion of remote working career opportunities, the online classes really prepare students how to collaborate and work from a distance."

Ryan Ballard had been a working artist in New Orleans for nearly 10 years when he decided to enroll in the Academy's online master's program for sculpture in 2009. He had already designed several public art installations in the city and was in the midst of creating a science fiction-themed Mardi Gras parade club.

He figured he could knock out the online master's degree while still working in New Orleans, given the flexibility the school was advertising. But almost from the start, he felt frustrated with the coursework.

Some of the classes were very basic, like figure drawing, while others required complicated and expensive equipment that he had to purchase, he says. For a small-scale bronze casting and jewelry-making class, for example, he said he had to buy nearly $15,000 worth of supplies, including a crucible and a vacuum chamber for pouring and heating bronze. Often, he'd only find out about the supply lists a few weeks before the beginning of class.

"It had no application to my work, and I felt as a graduate student that I should be choosing the type of work I want to do," Ballard says.

Toland, the spokeswoman, called Ballard's situation "an anomaly."

"I've never heard of someone spending that much money on a single class," she says. "The choices a student makes for materials and how much to use is up to them. Teachers usually don't dictate that to the class."

Ballard says there were a handful of professors he admired, but most were unremarkable. And the online format created problems. Professors often did not respond to emails or other questions for days, he said, and the work was never graded on time.

He often thought about dropping out, but with tens of thousands of dollars already paid, Ballard decided to stick it out. He graduated earlier this year and said he is resigned to the fact that he'll be working the rest of his life to pay back the more than $100,000 he borrowed for classes and supplies.

Ryan Ballard took online graduate courses at the Academy. He was not satisfied with the quality of his education and is now in debt. (Photo courtesy of Ryan Ballard)

"That's a big sword hanging over my head," he says. "It's like you get yourself so far into debt that you can't afford to lose. You just have to kick ass all day long. I'm taking on crazy production jobs left and right, and a lot of it is specifically for the purpose of just trying to kill this debt."

‘'HE MYTH OF THE STARVING ARTIST’'

As for-profit higher education has grown rapidly in recent years, arts-related majors have proven a popular way for companies to expand enrollment and enter new markets.

Education Management Corp., a publicly traded corporation that is the nation's second-largest owner of for-profit colleges, grew its Art Institutes chain from 22 schools in 2001 to 50 by last year, operating in 24 states, according to the company's securities filings.

The Academy of Art's enrollment has grown from fewer than 6,000 students in 2000 to more than 18,000 students last year. The school generated revenues of more than $247 million in 2009-10, when the student population was about 17,600, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Department of Education.

By comparison, Ashford University -- another for-profit school -- posted $444 million in revenues with a student enrollment of 63,000 in the same year; the University of Phoenix's online campus generated more than $3.5 billion in revenues, with more than 307,000 students.

A trade school at its core, the Academy of Art is rooted in the assumption that illustrators, painters and photographers can be trained from the ground up, regardless of past experience or talent.

"When students begin here, we start off giving everyone a basic foundation. We show them how to sharpen their pencils, how to set up their easels and then go on from there," says Rowley, the Academy executive. "Other schools don't all offer that same fundamental level of training and that, I think, is the reason behind the myth of the starving artist."

Up until the late 1990s, the expansion of arts schools nationwide had been relatively modest, held in check by selective admissions policies and a general assumption that the arts field did not have a well-worn career path.

"Historically, you really couldn't peddle art as the ticket to fame and fortune," says Barmak Nassirian, a higher education consultant and former associate executive director of the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers. "What the for-profit business did was to turn it on its head. It's really the story of over-the-top marketing of unthinkable paths to wealth. It's like advertising low-income social work as a way to become a millionaire."

Spend any time perusing The Daily Show or other late-night television, and you're bound to see advertisements for arts programs that claim to specialize in getting students jobs in video game design and animation. The Academy of Art's advertisements feature the slogan "Jobs for the 21st Century" and urge those watching to "bring your dreams to life." A commercial for film production majors includes an instructor saying, "Our students are working everywhere in the industry." In a video game design advertisement, the narrator says: "Our graduates hit the ground running, and can work at the best gaming companies in the world."

The onset of more sophisticated advertising campaigns, combined with an economic recession that has sent millions into the ranks of the unemployed, has led to a boom in the arts school field -- particularly at institutions with open admissions policies and a desire for revenue growth.

Although Academy of Art has a longer history than some of the newcomers to the business, the school's fastest period of growth has come only in the past decade, following the trends of other for-profit colleges that have rapidly expanded.

Arts schools rank among the most expensive in the nation, according to Department of Education statistics, but research has shown that fine arts degree holders have some of the highest unemployment rates of recent college graduates.

A study released earlier this year by Georgetown University's Center on Education and the Workforce found that college graduates with arts degrees face an average unemployment rate of 11.1 percent. That compares to a 9.4 percent unemployment rate for humanities and liberal arts graduates, and a 5.4 percent unemployment rate for recent graduates in healthcare-related fields.

Because of the way the Department of Education collects statistics, it is difficult to know how many students at any institution get jobs after graduation. Not all schools are required to provide job placement rates, and some college accrediting agencies that collect such data have found inflated statistics at some for-profit schools in recent years.

The Obama administration has tried to get a handle on the issue by requiring career training schools -- including for-profit colleges and some non-profit vocational schools -- to provide statistics on how students are able to manage their debts after college.

The Academy of Art performed fairly well on tests of students' debt when compared to other for-profit arts schools. But on average, only a little more than 50 percent of its students were repaying at least a portion of their debt within a year, according to the data, and less than a third of students in the school's undergraduate cinematography program were repaying loans.

By comparison, at the Art Institute of Philadelphia and the International Academy of Design and Technology in Tampa, Fla., only about 20 percent of students in some arts programs were able to repay at least a portion of their student loan debt after graduating or dropping out.

"The issue is: Where is the tipping point?" says Stephen Rose, a research professor and senior economist at Georgetown's education and the workforce center. "People are going to school somewhere that they might enjoy, and there are some successes. So what has to be the balance between success and failure that you say is a good investment? What number is the right number?"

Academy of Art is not the most expensive of the nation's arts schools, but, at $18,050 in tuition and fees per year, it is among the top ten percent of the priciest four-year, for-profit college programs, according to Department of Education data. The cost of living in San Francisco drives up the total price tag to more than $36,000 per year, according to the government figures.

Opinions of past and present students vary widely on the cost of the programs, and the motivations of those running the school.

The university's sink-or-swim mentality stirs complex emotions among its students: an open enrollment policy offers a foot in the door for those without formal training, but it also boosts the risk of failure and a life of debt for those who don't succeed.

Molly Maloney worked three jobs while attending the University of Wisconsin for her undergraduate degree, feverishly saving money and avoiding any scrap of student loan debt. The decision to attend Academy of Art came as a tough choice: she knew she wanted to do game design, but she knew the decision would immediately plunge her $30,000 into the hole.

"I knew there was going to be debt hanging over my head," she recalls. "I knew that there was a good chance I'd graduate and not be able to pay it back, because when you're an artist you never assume anything. Trouble is, if that's your passion in life, unfortunately you can't really turn that off, and you're never going to be really, truly happy doing anything else. So I just said I'm going to do this thing."

Molly Maloney was offered a job as a concept artist for a video game design company during her last year at the Academy of Art. (Photo Courtesy Molly Maloney)

The decision paid off for Maloney. A year before graduating the master's program, she already has a job as a concept artist for a video game design company; an industry recruiter saw her work featured in this year's spring show, which led to an internship and a job.

Yet for many others, the gamble wasn't worth it.

Raya Golden came to the Academy of Art in 2002, drawn to its animation and illustration programs. Promises of a more than 90 percent job placement rate kept her going, but by year three she realized from talking to other graduates that the definition of a "job placement" was malleable. Many other illustration graduates were finding only part-time, unsteady work in a highly competitive field.

After graduating in 2008, she bounced around the Los Angeles area, looking for work drawing storyboards for the movie industry. The steadiest gig she found was managing an arts supply store in Santa Monica. By early this year, her $80,000 in loan debt had ballooned to more than $130,000 after interest. Her mother, who co-signed the private student loans, faced the prospect of losing her home.

Raya Golden studied illustration and animation at the Academy of Art. (Photo courtesy Raya Golden)

"I come from poor people, and all I wanted to do was take something that people had been telling me my entire life I was good at, and make a business out of it," she says. "That's all I wanted to do, that whole American dream thing. And I felt really tricked when I got out."

In a stroke of luck and benevolence, Golden had an uncle who recently scored a major contract in the entertainment industry. He offered to pay off her loan balance entirely if she would agree to work for him in New Mexico.

Nonetheless, Golden has watched her alma mater continue its expansion as friends who have graduated struggle to find jobs and maintain debts. She takes a dim view of the Academy of Art's future.

"The bigger it gets, and the less teachers care -- because their classes are overrun and not organized well -- the worse the art is going to be. Anything that has to do with the quality of the trade is going to disappear," she said. "It's going to destroy itself."

This story originally appeared in Huffington, in the iTunes App store.