"People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them." -- James Baldwin

I remember reading "Sonny's Blues" in high school. Baldwin's prose had aching immediacy that made me question if I was being haunted by ghosts of the past, or if I had stumbled upon an alternate universe in present-day New York, where Sonny and his brother grappled with questions intrinsic to the human condition. My throat caught as I devoured each paragraph of the text, reading myself between the lines. The work was written in the '50s with Harlem as its backdrop -- both environments foreign to my Generation Y, South Texan context. And yet I related. I related because the work had an intense sense of universality when it explored themes of self-discovery, ambition, and loss.

Amazing Grace tries to be another "Sonny's Blues," not through narrative, but through subtext. It appeals to morality and faith and aims to somehow prove the existence of a uniting connection among all demographics, regardless of race or gender.

It fails.

History is a conundrum. It's the subjective chronicle of how we arrived at our current state, and it misleads as well as informs. For millennia, human beings have harbored an unhealthy desire to preserve their own stories for posterity -- through cave paintings, papyrus, oral tradition, vellum books, paperbacks. We want to be documented the way we see ourselves. We want to be heroes.

We also want to find heroes, and villains, and protagonists/antagonists. We like to study history because we believe Edmund Burke's cliché: "Those who don't know history are destined to repeat it." And so we focus on characters like John Newton and decide that they can stand for some expansive vision of an era. This is our folly: as a society, we're too attached to the individual, and our own hope to uncover an extraordinary man clouds our judgment of the bigger picture.

Set primarily in 1744 and 1745, Amazing Grace depicts Newton's story, its timeline revised ever so slightly for the sake of tidiness. Newton, a slave trader and member of the British Royal Navy, undergoes a fantastical journey to find God and denounce his facilitation of the Middle Passage. Meanwhile, his crush on childhood friend Mary Catlett blossoms as he matures, and a romantic triangle between them and a Major puts their love to the test. Of course, everything resolves itself seamlessly at the musical's conclusion, when audience members chant along to Newton's iconic hymn from New Year's Eve, 1773, "Amazing Grace."

As one can imagine, the plot is dotted with an impressive array of truisms and the consistent idea that everything will be all right as long as Newton accepts the Christian God as his savior (one should expect nothing else from writer Christopher Smith, who in his bio thanks the Lord "above all" for "mak[ing] this whole impossible dream a reality"). The religious bent contrasts nicely with Newton's bad boy persona in the first act but grows tiresome once he converts. Is there no way to invoke ethics without using overbearing Christian rhetoric? Even if the work requires Protestant allusions to respect the historical timeframe, must they be so stark and omnipresent?

Then, there's the issue of slavery. In my estimation, Amazing Grace does a great disservice to those who suffered under the lash, and those who still suffer today. A program note from authors Smith and Arthur Giron and director Gabriel Barre claims: "We have endeavored, not only to tell the real life story of John Newton, but also to illuminate the struggles of ordinary men and women who were prey to the evils of slavery and those who risked everything to end the hideous practice in Britain." I'm sure they did "endeavor" to convey such difficult, complex subjects in two and a half hours, but any sociopolitical message tucked inside their musical was lost beneath ardent displays of faith and dramatic (if often frivolous) depictions of love.

If it were not for Amazing Grace's shortcomings in depth and scope, the musical would be fine, albeit forgettable. Much like The Pirate Queen of 2007, the score is pretty, though heavy at times. No tunes are particularly catchy, and few audience members leave the theater humming anything but the titular song. Smith gets by with his music, but he doesn't border on genius.

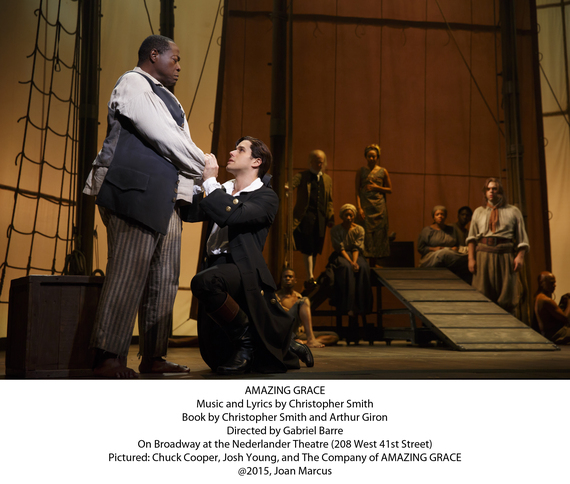

It's a shame that Amazing Grace disappoints because the cast is really talented. Josh Young plays a convincing John Newton, his voice billowing through the orchestra. Erin Mackey is a lovely Mary Catlett, though her abilities would be better showcased as a leading lady like Christine Daaé. Chris Hoch adds humor to an otherwise dry book, adroitly depicting the lovelorn Major Gray. And Laiona Michelle, who makes her Broadway debut as Nanna, has a gripping presence that could leave a huge impression if given the right role.

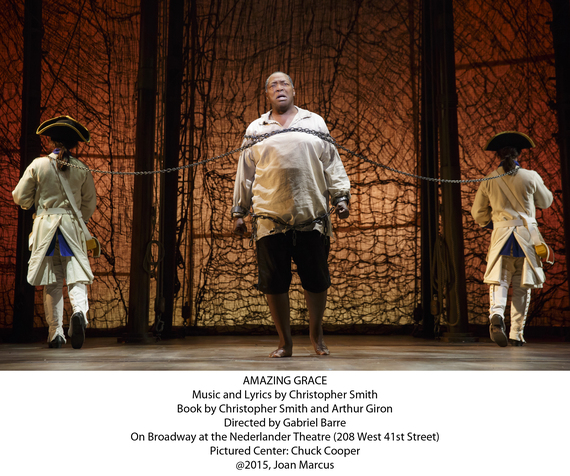

Tony winner Chuck Cooper is especially noteworthy as Pakuteh/Thomas, John's slave who is more like a father. As he admonishes John for his betrayal in "Nowhere Left to Run," his harrowing words send shivers down spines. This is not a testament to the brilliance of the song, but instead a result of the vocalist's talent. If Cooper recited the phonebook with the same kind of stern emotionalism, there would be nary a dry eye among his viewers.

But despite worthy performances from Cooper and his peers, Amazing Grace still feels... empty. It holds none of the potential for empathy in "Sonny's Blues;" instead, it attempts to reinvent history by denying the lasting presence of racism. Smith and Giron criticize slave traders for their cruelty and pat abolitionists on the head for recognizing the humanity of their black brethren. With the passing of Britain's Slave Trade Act of 1807, racism seems magically eradicated, and everyone holds hands and sings "Cumbaya" (or in this case, "I once was lost, but now am found;

Was blind, but now I see"). That's the history we want to believe, where heroes saved the day and lived happily ever after. Unfortunately, it's not the history that has led to systemic prejudice and racial discrimination for centuries since the events from Amazing Grace took place.

So why aren't we talking about our history, the one that keeps us up at night? If we're going to take period pieces to the Great White Way, they must have some resonance with a 21st-century audience. Or better yet, why not make a 21st-century musical for a 21st-century audience? Why not look at modern slavery, or racism that results in the shooting of nine innocent people at a church in South Carolina? As a symbol of solidarity for civil rights, why did financiers choose to throw their funds at a tale about a white Englishman who barely contributed to the abolitionist movement after almost a decade of fueling the slave trade?

As the curtain closes, Amazing Grace gets a standing ovation, with shouts and tears to boot. Maybe, I missed something. Maybe, I don't understand. It's okay that I don't like it because someone else did. But for me, it is not enough. It's too trapped in "history" to acknowledge the history that resides inside us.

Amazing Grace opened at the Nederlander Theatre on Thursday, July 16, 2015.