Our nation faces real, serious, long-term challenges to its future. Two of the biggest are restoring our global economic competitiveness and reining in the skyrocketing costs of medical care that have become, perhaps, the biggest obstacle to our long-term economic strength. Obesity, and the illnesses and lost productivity to which it leads, lies right at the center of both of these challenges.

The medical cost of adult obesity in the United States is difficult to calculate, but estimates range from $147 billion to nearly $210 billion per year. Lost productivity could cost many billions more. But a recent report shows us we don't have to bear such high costs.

When Congress proposes new legislation, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) generally estimates the costs of that legislation over a 10-year period. Most of the time, this is a useful guide to our leaders. But when legislation is designed to address long-term challenges and provide a long-term return on investment, that 10-year timeframe not only isn't enough, it actually puts blinders on our policymakers.

Families everywhere, even those with limited means, make sacrifices for their children. They buy healthier food even if it's a bit more expensive, look for good day care, or pay more for a house because it has good schools nearby. When parents do things like this, they're doing it because they know there's a long-term benefit for their children, even if it makes balancing the check book a bit harder now.

Economists tell us investments in our children pay off the most when made at the earliest ages. And isn't that what real investments are? Paying now in the expectation of greater long-term value. Our leaders in Washington need to heed families' examples, and invest in programs that will help ensure a healthy future for our children.

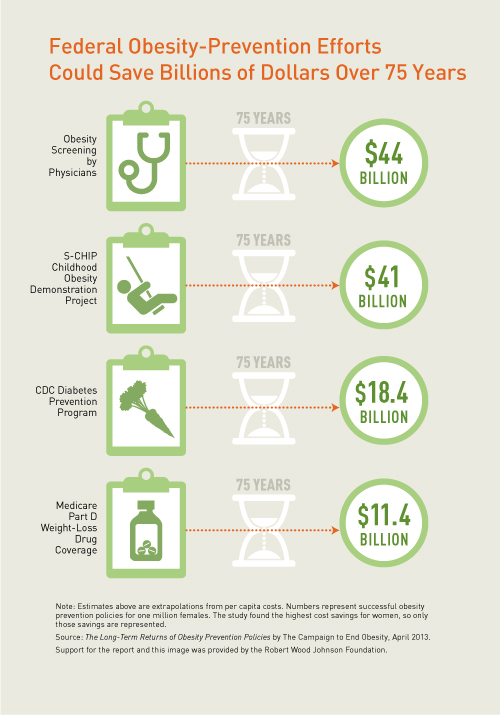

The new report by the Campaign to End Obesity shows that, for policies designed to prevent or reduce obesity, a 75-year window better captures the full extent of a policy's value. This is because efforts to prevent chronic health problems like obesity provide good value in the short term, but even more value when we look decades down the road.

The report identified billions in federal cost savings that programs aimed at any age -- even up to age 65 -- could provide, but noted that most of the savings occurred beyond 10 years. The savings materialize because, when people live longer at a healthy weight instead of being overweight or obese, they have lower health-care costs and earn more money in wages.

We know CBO can do these long-term estimates because they've done them in the past to examine the budget costs and savings from a proposed increase in the federal cigarette tax. And Social Security uses a 75-year window when examining its solvency. It's clear that, in many cases, the longer view is the more accurate one for balancing costs and savings. It helps clarify the difference between short-term costs and long-term investments.

That's the key problem with our current budget scoring process -- it creates a systemic bias against helping our children be healthy and successful. The costs of programs designed to help kids will be clear in a 10-year window, but the value can take longer to materialize, even though it can last a lifetime. Unless CBO and our leaders look toward the long term, we will continue to under-invest in our children -- in keeping them healthy and getting them educated and ready to succeed in a very competitive future. For children to do well as their parents want, and for our nation to do as well as we all want, that must change.