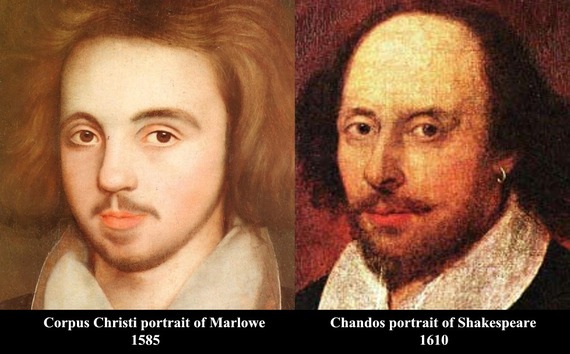

William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe were born 450 years ago, just two months apart. Marlowe's plays and poems, all written in his twenties, have been overshadowed by Shakespeare's. But the Shakespeare name only came to prominence after Marlowe's apparent demise, and he writes like a continuation of Marlowe, the two bodies of work blending so seamlessly at their join that some people wonder whether Marlowe wrote Shakespeare's too.

That the theory hinges on a faked death has led many to dismiss it. But is it so implausible?

At the time of his supposed death, Marlowe was out on bail, facing charges that would have almost certainly ended in his execution. Early that month Marlowe's former roommate, Thomas Kyd, had been arrested and tortured for his connection with Marlowe; within a year, Kyd was dead. Ask yourself this: Faced with the same circumstances, would you consider faking your death to escape?

To this day, people fake their own deaths to avoid criminal prosecution. Fame is no bar, as is clear from the temporary mortal departures of both John Stonehouse MP, and author Ken Kesey. Stonehouse was tracked down, Kesey broke his own cover, and both did time.

Former State Senator David J. Friedland staged a scuba diving death in the Bahamas in 1985 while awaiting sentencing for defrauding a pension fund. In the absence of a body, suspicions remained; Friedland was later arrested in the Maldives.

Lack of a body was also the undoing of Thomas Osmond, due to stand trial for sex offenses. Osmond committed pseudocide in March 1995. He left a note, and witnesses placed him at a bridge 80ft above Wales's River Usk, but a police detective tracked him down in Bristol three years later.

Marine Staff Sergeant Arthur Bennett's death in February 1994 was more convincing. Facing court martial for child molestation, he set light to his trailer in an apparent suicide. The charred body found inside was buried with full military honors in a veteran's cemetery, but it wasn't Bennett's. Three years later, when a man named Joe Benson was arrested in Utah on sex offenses, he was discovered to be the "dead" Arthur Bennett.

Clearly, a successful faked death requires that you avoid attracting attention. This principle was ignored by "canoe man" John Darwin. Declared dead after vanishing at sea in March 2002, he moved back to live in a room connected to his family home by a false-backed closet. In 2006, property hunting in Panama, Darwin and his wife posed for a photograph that was posted online by the estate agent. In September 2007 the "dead" man rang his wife at work, leading a suspicious colleague to go to the police. His claim of amnesia, when he walked into a police station that December, was easily unraveled through his trail of indiscretions.

Philip Sessarego demonstrated it is perfectly possible for a dead man to become a successful author. His family grieved him when his belongings were found beside unidentifiable remains after a Bosnian bomb blast in 1993. But Sessarego was still alive, and went on to write a novel under the pseudonym Tom Carew that became a best-seller. Temptations not available to Elizabethan authors were his undoing, and eight years after grieving the death of her dad, his daughter was shocked to see him interviewed on national television.

Faking death is an entirely plausible action for a person in a serious fix. Though we only hear about failed attempts, it is statistically reasonable to assume that some are successful. Even people who are actively being sought have successfully disappeared. How much easier to disappear when, as in Marlowe's case, no-one comes looking: a substitute body, convincing witnesses, an official inquest. How much easier to vanish four hundred years ago, before the advent of photographs, modern passports, finger-printing, DNA testing and traceable bank accounts.

No matter how much fame Marlowe had achieved as a poet and blank verse dramatist, few outside Cambridge, Canterbury and London would know what he looked like, including the Deptford-based jury. His alleged murder occurred not in a tavern as is commonly believed, but in a house identified by the author of The Reckoning, Charles Nicholl, as a government "safe house." Marlowe worked for the Elizabethan intelligence service, and all three men present that day in Deptford were either secret service colleagues or servants of Marlowe's patron Thomas Walsingham--himself a former intelligencer. Marlowe's "killer" was pardoned by the Queen with unusual rapidity and returned immediately to Walsingham's service.

There are other irregularities. The Queen's coroner, William Danby, conducted the inquest alone when it should have been jointly conducted with the county coroner. The chief witness, intelligence agent Robert Poley, was described by his well-respected contemporary William Camden as an "expert dissembler." The records paying him for the period covering both Marlowe's inquest and apparent demise reveal--uniquely--that he was "in the Queen's service all the aforesaid time."

Two weeks after Marlowe's inquest, the first piece of writing to appear under the name William Shakespeare was published. Shakespeare's early works are very similar to Marlowe's. They are also understandably a long way from the later heights of Macbeth, Othello and Hamlet -- the young writer having not yet developed the skills and style of a more mature one. Scholars acknowledge Marlowe as Shakespeare's chief influence, but it is perfectly possible to read their combined canon as the work of one man.

In questions of human behavior, one observer is quoted above all others. So for the final word on the plausibility or otherwise of faked deaths, let us turn to Shakespeare himself. The author was obsessed with characters being wrongly thought dead. 33 of Shakespeare's characters -- in eighteen plays -- are mistakenly believed to be dead for some part of the story. These include no fewer than seven deliberately staged deaths, three of which are faked to avoid a fatality. Taking into account Marlowe's parlous position in 1593, the ingenuity of human beings faced with their own destruction, and Shakespeare's obsession with false death, Christopher Marlowe's apparent demise is not the bar to authorship that many assume.

Ros Barber is the author of The Marlowe Papers, now available in paperback from St Martin's Griffin. She can be found at rosbarber.com or on Twitter @rosbarber.