"The man who kills the animals today is the man who kills the people who get in his way tomorrow. He recognizes the fact that there is a law that says he must not do this or that, but without the reinforcement of this law, he is free to do as he chooses." (Dian Fossey to Louis Leakey)

I can't wait to read Margaret Atwood's new book, The Year of the Flood. My motives are somewhat narcissistic. Over the weekend I noticed a huge spike in hits on my mostly dormant web page. At the same time, a forgotten article written two years ago about Dian Fossey and a spate of gorilla killings in Congo was enjoying a resurgence over at OEN News. Why the sudden interest in an ancient article? I hardly remembered writing it. This is why I love the internet. A few trackbacks later, I learned that Atwood's new book had bestowed sainthood on Fossey and her foremost biographer, Farley Mowat. Google searches on Fossey and Mowat had led people to my forgotten article.

International Primate Protection League Marker On Fossey Grave © G. Nienaber

Five years ago, Farley Mowat's biographer, Dr. James King, encouraged me in my somewhat crazy idea to write a first person biography of Fossey, set in heaven with her beloved gorillas as a kind of tragic Greek Chorus. The rationale was that the conceit honored the African tradition that the dead live on to protect their beloved on earth. Research in Canada led me to a treasure trove of materials on Fossey that Mowat had archived at McMaster University. It includes many of her letters. That is all I will say about my book and research, lest I fall into the trap the Fossey herself wished to avoid after she wrote Gorillas in the Mist. Fossey was on a book tour in the United States and bemoaned the fact that she was being forced to publicize her book. "People don't need the author shoving it down their throats," Fossey wrote.

Atwood's book, which sounds great according the reviews, is set in the future and after a "waterless flood" has killed most of the human race and a large portion of the animal kingdom as well. "God's Gardeners" revere Saint Dian Fossey, Mowat, and Al Gore among others.

The role of The Gardeners is described in the Wall Street Journal's more mixed review but here is a section that sums up their philosophy.

In this not-so-peaceable kingdom, many animals have become extinct. The Gardeners mourn their loss and revere such figures as Saint Jacques Cousteau and the "martyred" Saint Dian Fossey, "who gave her life while defending the Gorillas from ruthless exploitation." In a sermon toward the end of the book, Adam One, the theological leader of God's Gardeners, intones: "Let us forgive the killers of the Elephant, and the exterminators of the Tiger; and those who slaughtered the Bear for its gall bladder, and the Shark for its cartilage, and the Rhinoceros for its horn."

Mountain Gorilla © G. Nienaber

Personally, I think Atwood got it right by bestowing sainthood on Dian Fossey. Fossey wrote often to friends and family that she believed her African staff to be "the backbone" of her research station at Karisoke, located deep in the saddle region between Mounts Karisimbi and Visoke in tiny Rwanda. She would have been outraged at the 2007 headlines from Congo that detailed the senseless killing of eleven endangered mountain gorillas. But, more importantly, Fossey presciently predicted the current atrocities perpetrated against innocent men, women and children in Congo.

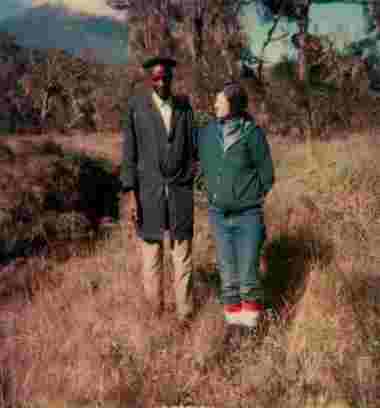

Dian Fossey and Tutsi Cattle Herder (McMaster Collection)

Dian and her ex-pat friend, Alyette DeMunck, were on an afternoon's stroll when the sight of a poacher's camp interrupted their idyll. Dian tells the story in her own words in a letter she wrote to Louis Leakey in 1968.

We were walking along a beautiful, isolated river, which flowed deep within the jungle's grasp of wild orchids, liana and senie. Alyette was a Belgian woman who had known Africa since her birth. She lost her husband, and had her son and nephew brutalized and murdered by rebel soldiers, yet she still managed to love the land. In fact, "love" is a trite word to describe her affinity with the continent. As I stood there, breaking bamboo snares one by one, our previously harmonious association was punctuated with a heated argument. My friend stood apart from me and very firmly asked what right I had, as an American living in Africa for only fourteen months, to invade the hunting rights of the Africans, since by birth, they owned the country. I kept on breaking traps, but at the same time I could not agree with her more. Africa did belong to the Africans, but I felt that written orders, whether they pertained to man or animals, should still prevail. If I could enforce the written rules of a supposedly protected park and prevent the slaughter of animals, then I should do so. As I continued breaking the bamboo, the reliable and flexible death trap of the last wild game of Africa, Alyette continued to plead her argument.

"These men have their right to hunt! It's their country! You have no right to destroy their efforts!"

Perhaps she was right that a destitute African living on the fringes of the Parc had no alternative but to turn to poaching for a living. At the same time, why should we condone a man who openly breaks the law; why shouldn't we take whatever actions we can against him? The man who kills the animals today is the man who kills the people who get in his way tomorrow. He recognizes the fact that there is a law that says he must not do this or that, but without the reinforcement of this law, he is free to do as he chooses.

Fossey struggled with this conundrum until the day she died, but at least she faced it.

By the time of her murder, one day after Christmas in 1985, poaching had been all but eliminated from the Virungas. Fossey learned to make peace with the inhabitants of the forest and even delivered a Batwa baby at her annual Christmas bash for the Africans in 1984.

It is most likely that it was Fossey's knowledge of gold and mineral smuggling rotes through the Virungas which led to her murder. It is doubtful that the myth of vengeful "poachers" led to her death.

Fossey Buried in the Gorilla Graveyard © G. Nienaber

Dian's true battles were with the minions of USAID, the conservation organizations which misappropriated the Digit Fund, corrupt local officials, and mis-guided "tourism" interests.

It seems we are fighting the same battles once more as history repeats itself in the killing fields of DRC. Perhaps we should all reflect upon her legacy and revel in her strength. It will not be an easy battle in the war against greed and corruption--from whatever the source.

Thanks, Margaret Atwood, for bestowing sainthood on a spiritual mentor.

++++++

This author is working on a narcissistic memoir about how Fossey led her to Congo. It will probably never be completed.