There's a thrill to each step taken in Turkey. It's the knowledge that underfoot, not more than a few feet, treasure waits. All one needs is the right swing of a pick, and Byzantine gold, Roman marble, and Ottoman jewels will spew from the ground like oil. The fact that each new construction project, especially in Istanbul, unearths some ancient ruin adds conviction to the belief. In Anatolia, a flash of marble in the ground is often tied to something much larger, as the remains of Ephesus, Troy, and Pergamum show.

Sixty miles east of Bodrum, in the upper Marsyas valley, yet another ancient metropolis is shedding more than a millennium of earth and sparkling in the sun again -- Stratonikeia.

My own discovery of the city was entirely accidental. After mentioning my love of archeology to the owners of 4reasons Hotel in Yalikavak, where I was spending a few nights, the proprietors alerted me to the nearby excavations. Better yet, they put in a call to the site's head archeologist, Prof. Dr. Bilal Söğüt, who invited me for a tour.

Although only mid-May, the land was hot and dusty as the car turned off the Yatağan -- Milas highway. Not yet an established tourist destination, there are no gates, no parking lots, no souvenir hawkers and no ticket booths -- just a pre-fab hut and a line of shaded picnic tables, where the perspiring, sun-leathered diggers chowed down a mid-morning meal. Being summer, work commences at sunrise and goes as long as the heat is bearable.

Although only mid-May, the land was hot and dusty as the car turned off the Yatağan -- Milas highway. Not yet an established tourist destination, there are no gates, no parking lots, no souvenir hawkers and no ticket booths -- just a pre-fab hut and a line of shaded picnic tables, where the perspiring, sun-leathered diggers chowed down a mid-morning meal. Being summer, work commences at sunrise and goes as long as the heat is bearable.

Dr. Söğüt, from the Department of Archaeology at Pamukkale University, welcomes me (and my translator, Ali Erulgen) to a shaded table for introductions and tea. An energetic man, he shifted and fidgeted in his seat as he spoke about the excavation process, the challenges, and of course, the story of Stratonikeia itself.

Stratonice was a princess, the daughter of Demetrius Poliorcetes, king of Macedonia in the third century BC. After marrying the king of Syria, Seleucus, she became a queen in her own right, ruling a portion of the Seleucid Empire. Being exceptionally beautiful and still young, her stepson Antiochus fell madly in love with her to such a degree, that he nearly died from depression. Fearful of losing him, the king, according to Plutarch, declared Antiochus king and gave him Stratonice. In her honor, Antiochus founded Stratonikeia.

He's clearly proud of his team. "Within the crew," he points out, "you can find archeologists, architects, art historians, restaurateurs, biologists, geologists, chemists, Byzantologists, computer technicians and painters."

Flopping on a dog-eared cap to protect his already heavily-tanned head, Dr. Söğüt leads us north to the to the village square of Eskihisar, the later Ottoman settlement which anchors the western end of the excavations and marks the beginning and end of tour. Ghostly even in sunlight, the weather-beaten stone buildings seem older than their age. The Şaban Ağa Mosque gets the most attention. Dating back to 1876, it's still a whelp by Turkish standards. But, its charm is timeless, mostly due to the graceful wood portico and conical balcony above the entrance. The sight will become even prettier once Dr. Söğüt and his team succeed in coaxing back the stream that ran alongside before mining sucked it dry.

Turning east, we head along Ağa Sokakları, the main boulevard of Eskihisar. Apart from five remaining families and handfuls of stray dogs and cats, the village is totally abandoned. What remains today is a line of impressive stone houses of the formerly well-to-do in various states of collapse. A few wooden sharia-style Ottoman doors still hang from the hinges, with one half for men, the other for women, and different doorbells indicating the sex of the guest. Despite their sorry state, Dr. Söğüt is not allowed to touch most of them. "Some of the private land owners allow us to clean and restore (as well as it can be done whilst still in the ground)," he explains. "But we can only excavate once the land has changed ownership." this is a problem throughout Stratonikeia. Despite clear indications of substantial archeology, several areas are off-limits.

Towards the end of the street, the Greek, Roman and Byzantine history becomes more apparent, often in the building blocks of the Ottoman buildings themselves. "Only in Stratonikeia," Dr. Söğüt points out, "will you be able to find antique and Ottoman structures next to each other on such a scale." Turning south, however, the remains became far more Hellenistic. The road we're walking down is itself is a miracle, Dr. Söğüt explains as he scuttles ahead, scooping up stray stones and placing them on a growing wall running alongside. Just a year earlier, he explains, passing here was nearly impossible. Calling a halt halfway down, he suddenly leaps off the side, down into a pitted, poppy-dappled excavation area, where a line of ancient Roman shops butt the road.

The pits gleam with newly exposed marble and reflect the intensifying afternoon sun, illuminating perhaps the greatest contrast between Stratonikeia and the other ancient sites in Turkey. Here, the shovels are throwing up dirt all around you, letting visitors share in the thrill of discovery. It takes some effort to restrain yourself from hopping in and lending a hand. At long-established sites like Ephesus and Hierapolis, the excavations are completed, off-limits, or occurring off-stage.

The pits gleam with newly exposed marble and reflect the intensifying afternoon sun, illuminating perhaps the greatest contrast between Stratonikeia and the other ancient sites in Turkey. Here, the shovels are throwing up dirt all around you, letting visitors share in the thrill of discovery. It takes some effort to restrain yourself from hopping in and lending a hand. At long-established sites like Ephesus and Hierapolis, the excavations are completed, off-limits, or occurring off-stage.

At the end of the road lies one of Stratonikeia most impressive structures -- a 2,400-year old Greco-Roman theater cut into a natural hillside. In its heyday, it held up to 15,000 people. It's in the orchestra that Dr. Söğüt uncovered some of his most publicized fines -- fifteen marble blocks engraved with 2,300-year-old reliefs of mythological gods.

Desperate for some shady relief, we retreated back north, passing greener pastures, where trees, shrubs, and tall grass wrap their tendrils and roots around any unattended remains. It continues as such past the odeion and bouleuterion until we reach the city's north gate, which Dr. Söğüt intends to eventually make the main entrance to the site.

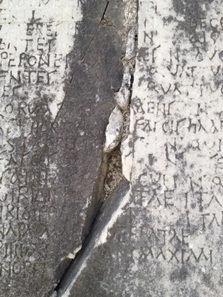

Stepping into the broad colonnaded street leading to it, it's easy to see why. This must have buzzed with activity back in the day, enough to leave cartwheel impressions in the huge marble blocks forming the road. Alongside, a vast agora reveals shops, mosaics, inscriptions, and even a comprehensive drainage system. At the end, a nearly complete 46-foot high and 140-foot wide arch bends over an elegant fountain pool still scarred with rope imprints from users. The pipes that fed the nymphaeum are still visible, as are the ancient symbols laid into the pool floor. Through the gate, the road once continued to a sacred precinct dedicated to Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft, magic, and necromancy.

It's also through the north gate that Stratonikeia earns the "gladiator" part of its current moniker. "We were able to excavate well-protected graves that belonged to gladiators," Dr. Söğüt explains. "All of the gladiators we were able to identify are from Stratonikeia and competed within this city and were treated as heroes." The inscriptions reveal much about the warriors. The garlands, for example, show the number of victories, while epitaphs often describe the gladiator himself. "Vitalius, a brave man at boxing, lies here," one reads, "whom mighty Polydeukes, good at boxing and worthy of his name, killed by his own hands in the arena."

It's also through the north gate that Stratonikeia earns the "gladiator" part of its current moniker. "We were able to excavate well-protected graves that belonged to gladiators," Dr. Söğüt explains. "All of the gladiators we were able to identify are from Stratonikeia and competed within this city and were treated as heroes." The inscriptions reveal much about the warriors. The garlands, for example, show the number of victories, while epitaphs often describe the gladiator himself. "Vitalius, a brave man at boxing, lies here," one reads, "whom mighty Polydeukes, good at boxing and worthy of his name, killed by his own hands in the arena."

Sport was clearly important to Stratonikeans, who built what might be the largest gymnasium in antiquity in the 2nd century B.C. just west of the north gate. "The 105-meter (344 feet) wide and 267-meter (875 feet) long complex served both as a sports center and a classroom, where history and philosophy classes were given in the past." Part of Dr. Söğüt's plans for the site includes recreating the complex digitally, but until then, there's plenty left to project it easily in your mind.

The future looks bright for Stratonikeia, at least brighter than its recent past. As Dr. Söğüt points out, "Helping the city to flourish financially, we can find a way to excavate and discover many new structures and restore them." So for the love of Stratonikeia, add it to your next Turkey itinerary. The sooner you go, the more you'll have it to yourself.

All photos by Mike Dunphy, except door photo, by Ali Erulgen (with permission)