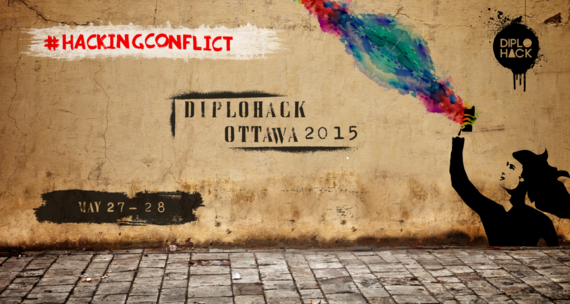

What kinds of people could be more different than diplomats and tech-developers? The first wear midnight-blue suits in the corridors of power; the latter wear sweat pants in Californian cafés. And yet it is these two groups that an organisation called DiploHack has thrown together to solve real problems - like corrupt government, sexual violence or the use of internationally prohibited weapons.

In events generally lasting only a weekend, the diplomats and techies, as well as entrepreneurs, journalists and NGO workers, are effectively locked in a room until they make something that can ameliorate one of these problems. The thinking is that by smashing together very different kinds of expertise under high pressure, you create a reaction. And the results can be impressive.

It's like Iron Man for programmers

A DiploHack in Ottawa created a crowd-sourced means of tracking the production and use of barrel bombs - crude, untargeted weapons that often kill civilians - in Syria. The team made a website where anyone can upload pictures or information about any part of the supply chain - whether production, delivery or use. Their concept is that because the Syrian war is 'the most socially mediated conflict in history', they can crowd-source scrutiny of the bombs - and so bring international pressure to bear.

Another project investigated whether politicians had a conflict of interest in relation to businesses. Simply by combining political affiliations with databases of work histories and social networks, they were able to get striking results about people controlling huge sums of public money.

Creating something like that in a weekend is intense, to say the least. One programmer described as 'like Iron Man for programmers. A real test of your character'.

Apolitical spoke to Daan Eijwoudt, a young diplomat with the Dutch diplomatic service, which is where DiploHack began. One of its champions, both spreading and developing the concept, he spoke to us about why this isn't just a gimmick, why the Dutch are so innovative and what he caught the diplomats doing while the techies were hard at work.

Your first DiploHack was run by the Dutch Embassy in Tallinn, Estonia, and focussed on internet freedom. How did the public servants take to working like techies?

It was interesting to see. These kinds of hackathon-type events tend to be for the start of a company, non-profit or profit, but this was kind of different. Especially for people in diplomacy and working in the public service - we were partners with the Estonian government - it was new.

What can these two groups bring to each other?

It's a combination of the world of diplomacy, which is rather serious, where people are more formal and look in very broad terms and always find a certain balance with the entrepreneurial spirit - working under a lot of pressure in a way which is more binary and way more 'OK, we have to solve it now', and there's only one solution we'll go to. It's combining two different worlds that are really very clashing.

And what did the culture clash look like?

I had to laugh because what I noticed on the first day was that the developers were sitting together and already looking for potential solutions. The diplomats were doing something completely different, and very typical - they were networking. They were drinking coffee and talking to each other.

DiploHack has now spread across the continents, but didn't it come from very humble beginnings?

I was working as an intern back then at the Embassy in Estonia, in Tallinn, and we were asked to organise something for Human Rights Day. Estonia is not a country very much threatened by human rights abuses, so I was looking to do something different from the standard lecture by an ambassador or a movie screening. We wanted to develop something that people would actually remember.

I called around other embassies and asked them what they did in the last couple of years. Because of course we don't have to develop the wheel ourselves - you can just copy-paste great initiatives. And I got a phone call from this Dutch guy in London, who'd just done the first trial of DiploHack.

What was the most interesting project to come out of that first one you worked on?

One of the challenges we chose was public spending and the connection between politicians and their backgrounds in business. How can you find out what the clashes of interest are, and how their background might affect their sense of, well, neutrality? How neutral are they? They might have shares in a certain company; they might be the brother of a certain person. So the challenge was how to find out whether there are potential - because it's of course not a clash of interest legally - but potential clashes of interest.

And what did the team come up with?

They developed a website based on open data, combining a lot of databases. They took the people on the board of the Estonia Investment Agency, people in charge of a lot of public money. And they combined the information about these people with their LinkedIn profiles, their networks, but also with their party memberships. And what came out was that the vast majority were members of the two main right-wing parties in Estonia, which were in government at the time. In itself, it doesn't mean anything, because that's just a link, which might be very well explainable, it might be that they are more entrepreneurial people and so more willing to be in this party.

Yet, at the same time, it gives research journalists looking at this sort of thing a platform to start from. The information was all out there, but you would have had to do really a lot of work to connect all the dots.

What do you think of the barrel bomb crowd-sourcing done in Ottawa (see introduction)?

That was a very good example, a very concrete outcome, where you could see what could happen in such a little group in just a weekend. Just putting people with the right background together, locking them in a room and saying: you can only leave when you've found a solution.

It sounds like a great approach; what are the downsides?

One of the weaknesses is that people are put on the project for a certain amount of time, so the projects don't always carry on properly afterwards. It's not the same people who are super-enthusiastic about the event - and who are often interns or junior employees - who will be the ones to implement it afterwards. We've had the King of the Netherlands, we've had two Foreign Ministers, we've had a Director General at the events, so people are aware of them, but so far it's more to show how innovative the Netherlands is, look at these cool things we're doing, and not something people higher up the organisation see as a means of solving problems. [Indeed, there has been little recent activity on, for example, the barrel bomb crowd-sourcing project.]

Why did this way of doing things resonate with you; do you have a tech background?

Not at all, I just see that we live in a time where things like Big Data and Open Data and these ways of looking at problems, they're bypassing big Ministries like the one I work in, which could hugely benefit from them. Especially when you look at conflict, development policy. But people with a background in law or politics are not always as interested and as open to these kinds of developments. They might see that it has huge gains for the economy or start-ups, but they think, 'well, that's them, it's not us. We do things differently.' And I disagree. I think we can do something with it. We just have to find out how.

At Apolitical we keep hearing about new, bottom-up ideas coming out of the Netherlands. Are the Dutch just more innovative?

We're not very hierarchical, so it's very easy to come up with new ideas and to persuade your superior of the benefits. When we hear about initiatives like this, a lot of us think: why not just give it a shot? We try a lot, we do a lot, but I think that's also the major weakness with innovation in general in our field. Every month someone has a new idea and then in the end no one feels responsible for developing it, because there's always another idea coming along behind.

- You can find Daan Eijwoudt and DiploHack on Twitter. At the time of writing, DiploHacks are being held this month in Athens, Bratislava, Prague and Brussels