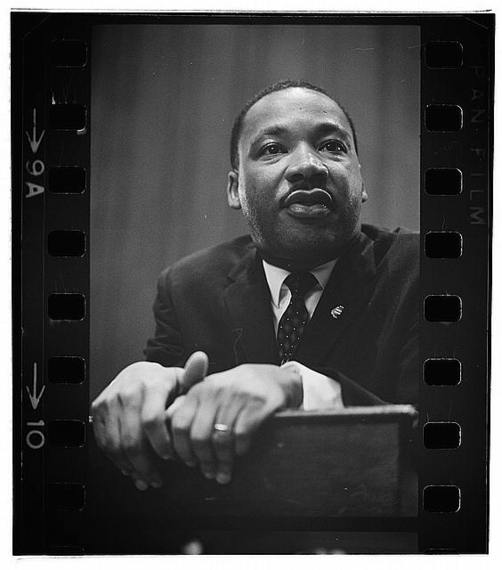

Many of Martin Luther King Jr.'s best-remembered quotes deal in poetic generalities or abstract universal ideas: love driving out hatred, or a long moral arc bending towards justice.

King's poetic imagery was a powerful tool for reaching people, but he found sentimentality hollow when not paired with honest speech and direct action.

When he recognized hatred in racist politicians or businesses, he would publicly call them out, descend on their town with demonstrations, stage boycotts or sit-ins at their establishments. He often reminded us that though the moral arc of the universe bends towards justice, social progress comes "through the tireless efforts and the persistent work of dedicated individuals," and never "on the wheels of inevitability."

King believed in loving his enemies, but he wasn't afraid to make them.

It can be difficult to remember that a man who has been so universally celebrated in death was seen in life as a radical. When Martin Luther King Jr. gave his iconic "I Have A Dream" speech at the March on Washington in 1962, twice as many Americans had an unfavorable view of him as a favorable one.

Today there isn't a more fondly remembered and respected public figure than King, but did our opinion of him change because we embraced his ideas of radical justice, or did we simply forget them?

Islands of Poverty

To King, racism was inseparable from poverty. Genuine equality, he believed, meant much more than eliminating overt segregation, it meant addressing cycles of inequality. King referred to majority black ghettos as "island[s] of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity," and considered this economic segregation an even greater challenge than legal segregation:

"It's much easier to integrate a lunch counter than it is to guarantee a livable income and a good solid job. It's much easier to guarantee the right to vote than it is to guarantee the right to live in sanitary, decent housing conditions."

His hope for ending this economic segregation lay in questioning larger systems. "True compassion" he said, "is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring."

The Greatest Purveyor of Violence

When discouraging the violence of those angered by racism and poverty, King was regularly asked how the United States' use of violence to solve problems was any different. The question "What about Vietnam?" affected King, eventually leading him to denounce the war, and refer to the United States government as "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today." To King, war, poverty, and racism, were interrelated symptoms of a larger societal illness:

"We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered."

In a series of speeches toward the end of his life, King repeatedly warned that none of these triplets could be eliminated while the others remained.

A Single Garment of Destiny

King's understanding of deep interconnectivity didn't stop at our borders. He firmly believed that racism and colonialism were two chapters of the same story, a "common cause of minority and colonial peoples in America, Africa, and Asia struggling to throw off racialism and imperialism."

King's famed admiration for Ghandi's leadership in nonviolent rebellion was not isolated. He drew inspiration from Kwame Nkrumah, who led Ghana to peaceful independence, he spoke of a brotherhood with those under South African apartheid, and encouraged America to support any people seeking its independence. As with the triple evils, he felt that if only colonialism or only racism were brought to an end, the other would persist. Still, he was certain that powerful changes were brewing:

"A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth. With righteous indignation, it will look across the seas and see individual capitalists of the West investing huge sums of money in Asia, Africa, and South America, only to take the profits out with no concern for the social betterment of the countries, and say, "This is not just." ...The Western arrogance of feeling that it has everything to teach others and nothing to learn from them is not just."

When king spoke about justice for all, he meant all of humanity: "a universal brotherhood" united in a "garment of destiny."

A Common Cause

King feared that though the United States had the potential to lead a global revolution of values, it would find itself on the wrong side of history.

In recent months, the nation has been sharply divided along racial lines in its interpretations of the Michael Brown and Eric Garner cases. It has been a powerful reminder that true racial harmony remains a dream. From those who lost nothing we have seen too few attempts to bridge racial divides by simply trying to understand the pain of communities that lost lives. But as perspectives clash, we should remember that King didn't fear tension. He believed in the power of tension to move us forward if we're only willing to face it.

When we avoid the uncomfortable in favor of our singular "cause," when we find ourselves outspoken in international politics but quiet on domestic injustice, we can learn a lot from King's message of unity. Nonprofits which often must struggle against one another for funding and attention, can accomplish so much more with direct, collective actions that reflect a shared understanding of justice.

If you care about poverty abroad, advocate for equality at home. If you care about equality at home, protest military spending that depletes public resources and promotes violence abroad. If you care about violence abroad, boycott domestic companies that support exploitation and a global imbalance of wealth along racial lines. If we view humanity as a family, as MLK dreamed, then we cannot justify treating social justice as a buffet or advocacy as a pastime.

Throughout his career, from his first speech addressing the organizers of the Montgomery bus boycott to his final speech addressing union organizers the night before he was assassinated, King called on those who would listen to "work and fight until justice runs down like water, and righteousness like a mighty stream."

In honoring the memory of Martin Luther King Jr., we should never dream of anything less.

Nathan Albright is the Community Discourse Coordinator at Nourish International

Martin Luther King Jr. Speeches and Letters