The governor of New Jersey has one secret that is not easily discoverable by pollsters, but more so by political scientists who study coalitions. It is no secret that Chris Christie is a Republican in a Democratic state, or that Republicans are a distinct minority in both the state's senate and assembly. But it is not well-known that New Jersey's office of governor is much-better endowed with executive powers than most of the other 49, allowing him a line-item veto as well as broad powers of patronage, making hundreds of appointments to offices and boards, from the Port Authority of New York to the Delaware River and Bay Authority, and from the Passaic County Sewerage Commission to the Supreme Court. Such appointments are the milk and honey of state politics, after which the professional class of donors, party faithful, lobbyists, staff, pensioners, expectant pensioners, defeated office-holders and broken-down administrators all hunger. An effective governor uses this extensive system of rewards to build and maintain support for his agenda -- not merely to gratify the fawning class for their faux affection.

One prominent example is the coalition Christie built on the issue of charter schools. For a decade, Democrats paid only lip service to urban demands for dramatic reform of public schools which, despite tens of billions of dollars infused, continued to be de facto segregated, rough and miserably performing.

But Democrats cherished the support of the teachers' union in particular and the public-employee unions in general and thus could not at the same time sincerely push for charter schools -- a position only tenable as long as Republicans in their leafy 'burbs were too stupid, or too white, to exploit it. But Christie as U.S. Attorney was not only smart, he was headquartered in the middle of New Jersey's largest city for seven years, and familiar with the ills of the city and with its lay-leadership who begged for reform.

Before 2009, no candidate for governor had wanted to challenge the well-organized and wealthy teachers' union, the NJEA, and all had gone meekly before the union leadership seeking its endorsement -- until Christie who, knowing he would never get it, announced loudly that he didn't want it. And while many gasped at this confrontation and proclaimed it folly, the math turned out to be in Christie's favor.

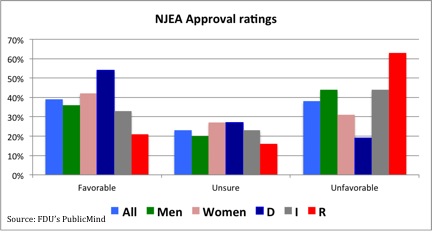

Christie's stance in support of charter schools for urban areas was unequivocal and voter turn-out in those dense Democratic hubs was curiously way down in that 2009 election when Christie beat the mealy-mouthed Democratic incumbent. Since then the state has moved ahead swiftly with charter schools, and Christie himself does not get the automatically-chilly reception from black leaders typically reserved for Republicans. Instead, he and the energetic, reforming mayor of Newark, Cory Booker, have made common cause. Meanwhile, even after buying millions of dollars of advertising against Chris Christie, the teachers' union finds itself with no more traction than when it started. New Jersey voters love their suburban schools, hate their urban ones, and split pretty evenly on the NJEA, leaving Christie with room to maneuver.

A second coalition case-in-point is Christie's sensitivity to the north-south split in political interests and culture. By some lights the state is really two entities, one a spreading suburb of New York City, the other the refuge for discouraged Philadelphians looking for bigger houses and cheaper real estate. More than a few disputes in the state trace their fault line to a place equidistant from the two great metropolises which are the first and fourth largest TV markets in the nation. To wit, there is one forlorn Atlantic City, decrepit and decaying like all of Jersey's cities but granted a remission in 1978 by a change in state's constitution, allowing Las Vegas to attempt to clone itself in the slums of the Jersey Shore.

The clone was a golden goose, providing billions in revenue for new state spending -- until other states got wise or discovered Indians, and Atlantic City revenues began their long and continuing decline. The remedy for the malady is much disputed. Some interests want to squash Atlantic City's monopoly on gambling to let the "industry" expand to compete statewide with other states by, for example, opening up for business the Meadowlands just outside of New York City so that, when fans aren't watching the Jets and Giants football teams play, they can hit the table games and the state can collect its tax on the mathematically challenged.

But these interests are opposed by those anchored in the south Jersey economy who fear that an expansion of gambling in the state will be the death knell of their ailing would-be resort town. Christie has so far sided with these south Jersey interests, many of them Democrats, calling for the state to do what it can to nurse the gaming patient: preserving its monopoly, giving multi-million dollar tax abatements to new projects, starting charter schools, and taking over many functions from the incompetent and corrupt local government. This has thus far endeared him to those with much to lose should Atlantic City be un-crowned as the east coast's gambling capital, just as it was unceremoniously dumped after many years as the site of the Miss America Pageant.

Christie's talent for coalition-building also won him serious changes in public union business. It was unlikely, for example, that Democrats would agree to any restriction on collective bargaining for public employees, but Christie was able to get assembly leader Sheila Oliver to go along with a legislatively-mandated reduction in benefits, partly by promising that assembly Republicans would vote for her to keep her job if her own caucus revolted. (At least, this is the governor's version of what happened. Oliver disputes the details.)

In short, Christie usually knows when to hold 'em and when to fold 'em. Schooled in the U.S. Attorney's Office, he has proven skillful at putting the deal on the table, letting everyone bitch about it, and then pressing his case and prosecuting detractors in public.

Thus, Christie has made a dramatic contrast to his several predecessors: Christine Todd Whitman who was considered Republican-lite, Jim McGreevey who was savvy and charming but frequently without an agenda or sincerity; and the hapless Jon Corzine who sought to be loved and admired by Jersey voters but spent every weekend in New York apparently with the people whose love and admiration he really wanted. By contrast, Christie pursues a popular agenda, reaches into the cities, builds coalitions, and gives as good as he gets from detractors. Just as important, he's a good tactician, adept at exploiting existing divides to build ad hoc coalitions that serve to pass his bills and keep the opposition fractured.

Whether these traits travel well into a second term or into a national campaign is not the point. The point is that those traits explain why a Jersey guy is of interest to people not lucky enough to live between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers.

Dan Cassino and Peter J. Woolley are professors of political science at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Madison, New Jersey. Cassino is Director of Experimental Research for the University's research group, PublicMind: Woolley is its founding Executive Director. This was the third in a series on Chris Christie.