Bostonians in the aftermath of the Marathon bombing like to remind themselves that Boston is strong. A similar sentiment was echoed hundreds of miles to the south in New Orleans on the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. Its slogan is "Resilient New Orleans". Yet, beneath the slogans, Boston and New Orleans still suffer pessimism reflecting deep racial and economic divides.

Painting by Dwayne D. Conrad. "it's good to wake up in the morning and say 'hey man, how you doing'? You don't get that everywhere. This is one of the few places where somebody will actually say 'man, how you doing this morning.' Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH New

Painting by Dwayne D. Conrad. "it's good to wake up in the morning and say 'hey man, how you doing'? You don't get that everywhere. This is one of the few places where somebody will actually say 'man, how you doing this morning.' Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH New

On the surface, puritan Boston and rollicking New Orleans would seem to have little in common other than rich maritime histories. But the old colonial capitals of New England and New France are also wedded by trauma. Boston's wrought by terrorism; New Orleans's by natural disaster. And both cities have had to answer a hard question: After a city unites in the face of trauma, how do you keep it united?

New Orleans' artist Dwayne D. Conrad says residents are united in their love for their city.

"My brothers tease me all the time. Why do you like New Orleans so much? Man, I'm like 'I fell in love with it. And, this is home. There's no place like this place."

Conrad standing outside a gallery in the French Quarter exemplifies this city's come-from-behind spirit. He was among thousands whose lives were greatly altered by Katrina 10 years ago.

New Orleans' artist Dwayne D. Conrad says residents are united in their love for this city but he laments growing gentrification. Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH New

New Orleans' artist Dwayne D. Conrad says residents are united in their love for this city but he laments growing gentrification. Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH New

"Oh yeah. I lived in the Lower Ninth Ward all my life. Loved that area. Loved the people. Loved my families there. But yes, we had to vacate. "

He lost his home, but Conrad is back in business. The French Quarter -- barely touched during the storm but impacted nevertheless -- is also back. And the infamous Louisiana Superdome not far from here, where so-called refugees in their own city survived hellish conditions -- has long been restored to what it was meant to be -- a stadium.

"The people of New Orleans have done something really miraculous."

Mayor Mitch Landrieu says Katrina offered a rare opportunity to rethink a battered city.

Mayor Mitch Landrieu puts a different spin on the demographic changes in New Orleans. Mayor Mitch Landrieu puts a different spin on the demographic changes in New Orleans. Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH News

"We realized that it took a lot of years for the city to deteriorate and we chose not to build the city back the way it was. We chose to build it the way it should have been."

But if built, "The way it should have been," says Dwayne D. Conrad, it would be inclusive of all its residents. And that he argues, despite his love for this city, is not New Orleans today.

"You know you have those that have and have-nots and those who have a lot. So we still got a lot to learn. We have to learn to pull together more. And these past few years I haven't seen it. And that's what hurts."

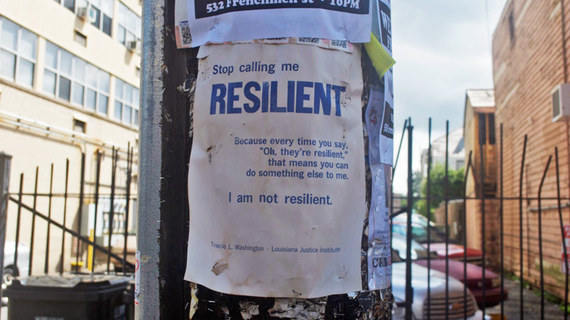

The slogans that have bolstered spirits in the aftermath of tragedy -- Resilient New Orleans and Boston Strong -- suggest unity, but some like Bostonian Alex Ponte Capellan are pushing back against the very notion.

"These messages kind of distract people from what's really going on. And it's just like a marketing campaign to like get everyone thinking that everything's fine and dandy when there's real issues happening like gentrification."

And that says Ponte Capellan, a 21-year-old housing activist, is the crisis facing both New Orleans and Boston: Poor and working class residents pushed out by rising rents and gentrification:

"Things that are happening in New Orleans is just a way for people to come in and take over, he says. "People are stranded and a lot of homes were destroyed and it just gives people room to come in and swoop in."

Alex Ponte Capellan is one of several activists who set up a "tent city" recently to protest a planned housing development in a working class section of Boston's affluent Jamaica Plain neighborhood known as Egleston Square. Capellan complains that the "affordable housing" aspect of the planned community provides little in the way of relief for poor people in the area, who survive on less than $25,000 a year for a family of four. He says New Orleans and Boston have much in common that way:

"I see similarities to in Boston when people were displaced for the highway they were trying to build through communities of color. A lot of people were displaced and a lot of vacant land was left and now that vacant land is being redeveloped today."

Egleston Square affordable housing activists, Yohana Beyene, Alex Ponte Capellan (seated in middle) and Josmar Torres

Egleston Square affordable housing activists, Yohana Beyene, Alex Ponte Capellan (seated in middle) and Josmar Torres

It's a concern echoed by artist Dwayne Conrad 1400 miles away in New Orleans: "Since Katrina you see the gentrification that's going on in this city and it's rampant."

Before the levees broke, New Orleans was 66 percent African American. Today, it's less than 60 percent, a loss of about 100,000 black residents. They have been replaced by thousands of young white artists and professionals pouring into the city.

Luther Gray was among those who left the city. "We had eight feet of water in our house. I have two sons. My wife, myself, we loaded everything we had. You know my wife's family lives about 60 miles between here and Baton Rouge in Gonzales, Louisiana. So we went there and we realized after the third or fourth day after Hurricane Katrina, 'wow, we're going to have to enroll our children in school out here."

Luther Gray is the curator at the Ashe Cultural Center -- a noted African American landmark near the Industrial Canal. His family found its way back but he laments those who never returned or are being pushed out by high rents. He says the wealth moving in leaves New Orleans poorer for it.

"Oppression has been long lasting here. And there has not been much economic equity, but this is where our rich culture comes out of -the poor neighborhoods."

Mayor Mitch Landrieu puts a different spin on the demographic changes.

"It's still a majority-minority city. That's never changed. We have about ninety percent of our people back -- either physically in New Orleans or in the surrounding counties, what we call parishes. It's about 1.4 million people are back."

And what some residents of the city see as gentrification, Mayor Landrieu sees as restoration and the resilience reflected in New Orleans's optimistic slogan.

"What Katrina did was it really held up a mirror and it forced us to look at ourselves and it forced us to acknowledge that for forty years we have been treating each other poorly," says Mayor Landrieu. "We haven't been creating the jobs that everybody needs, that political leaders and business leaders had made bad decisions. Although we still have significant problems in the city -- of crime, of violence, of racism -- the city has made tremendous strides in preparing itself to be a twenty first century city. It's been a pretty amazing story of resurrection and redemption."

In Boston and New Orleans, black, Latino and whites are of two different minds about the strength of a city to bounce back from trauma and the actual meaning of resilience. In Boston, Mildred Parilla, a low income tenant in the city's Roxbury section, whose landlords is threatening to double her rent, says Boston would only be strong if its poorest residents -- black, latino, white and asian -- were to unite. In Spanish she told me:

"A more relevant slogan when you think about strong you think about the unity is strength and especially the unity of people who are being taken advantage of; who are being oppressed, who don't have economic power."

Mildred Parrilla, a low income tenant in Roxbury whose landlord is threatening to double her rent, says Boston would only be strong if its poorest residents -- black, white, Asian and Latino -- were to unite

Mildred Parrilla, a low income tenant in Roxbury whose landlord is threatening to double her rent, says Boston would only be strong if its poorest residents -- black, white, Asian and Latino -- were to unite

Egleston Square affordable housing activist Yohana Beyene agrees.

"Boston Strong was a very reactionary slogan. There is an attack and the idea then is to get people to come together. But we want to sort of build a fight that's more sustainable and consistent. That doesn't wait for something to happen in Egleston or JP or Boston in general, but try to prepare for decisions being made about our community without our consent".

Boston Strong banner posted during Mayor Thomas Menino's last year in office at a construction site in Boston's Roxbury Section. Credit Phillip Martin

Boston Strong banner posted during Mayor Thomas Menino's last year in office at a construction site in Boston's Roxbury Section. Credit Phillip Martin

In New Orleans, a CNN Poll-USA Today poll found that a majority of whites believed the city had bounced back, while a majority of blacks did not. A resilient New Orleans to Luther Grey at the Ashe Cultural Center could only mean one thing:

"Where we are now is working toward equity in New Orleans where no longer will whites control everything and blacks are just subservient. We really want to be equal partners since of course we create most of the culture, including a lot of the food. Katrina was a turning point and we're trying to recreate the city in a better way. In a way that we can all see the future."

Mayor Mitch Landrieu -- the popular twice elected white mayor of this city agrees -- and says, albeit the divisions here, residents are united by their affection for the Big Easy:

"If you go see people in New Orleans they will complain like anybody else in the world complain about what it is that we tend to complain about everyday. But if you ask them whether they love New Orleans they'll tell you it's 'the greatest city in the world.'" Landrieu smiled and then laughed. "They'll say it's better than Boston."

And in the French Quarter, artist Dwayne D. Conrad, while lamenting the city's inequities, says "it is indeed the greatest city in the world."

"And you come here and you feel good. And it's good to wake up in the morning and say 'hey man, how you doing'? You don't get that everywhere. This is one of the few places where somebody will actually say, 'man, how you doing this morning.'

Dwayne D. Conrad says that is the New Orleans he's always known, and hopes a place where people say 'how you doing this morning' will not be replaced by the silence of strangers arriving to this rapidly gentrifying urban landscape.