This morning, I awoke to find that I had been copied on dozens of Twitter message exchanges among several people who were discussing the pathology of Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease, among human beings and mice.

My first thought was "Seriously?! It's too early for this!"

My second thought was "well, David, your Twitter sure has evolved from your pre-Lyme days when you used it mostly to promote vapid celebrity interviews."

As I began my morning caffeine ritual and read through each of the messages, I gained a new appreciation for some of the real complexities of "invisible" illnesses.

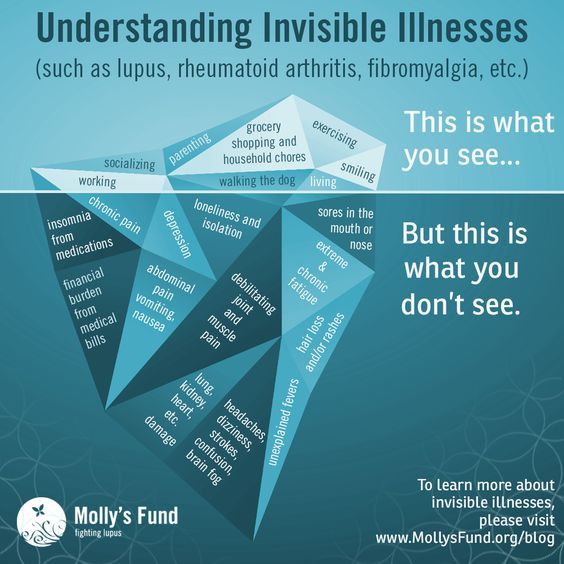

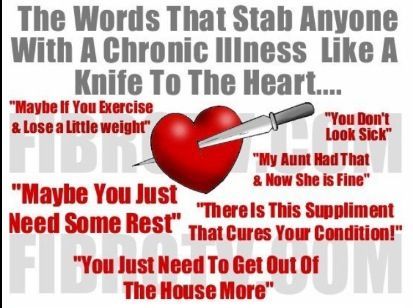

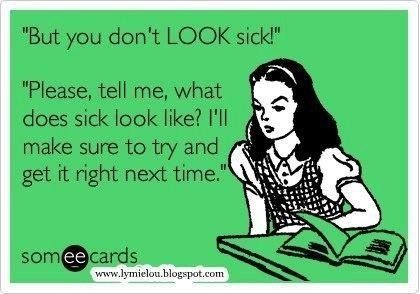

If you are connected with anyone on social media who lives with a chronic ailment, you've probably seen memes such as the ones peppered throughout this post. People who suffer with so-called invisible diseases use these to communicate the realities that they come to understand other people can't observe and, therefore, often can't sympathize with. As one of these people, even I sometimes get annoyed by the platitudes expressed in these "I'm an invisible illness warrior!!!" memes--yet I understand why people perpetuate them. If you don't, I hope you will keep reading.

Lyme is one of these invisible diseases, and the one with which I am most familiar; however, as it took many years of neurologists suspecting and testing for multiple sclerosis and other neurodegenerative disorders, I also understand that MS, early stage ALS, lupus, and countless other chronic illnesses very often leave a patient looking objectively well to both casual observers and to medical practitioners who invade and probe every possible aspect of their bodies.

People who have chronic illnesses frequently end up suffering alone in silence. Today, with the omnipresence of social media, many of us "scream" into the empty void of the world by posting these "invisible illness" or "silent epidemic" memes hoping that other people will see them and understand the unobservable suffering that we experience. At least as often as these memes effectively communicate such messages, they become an annoyance for the types of people who want their Facebook universes to be hubs of happy family photos, self-celebrating selfies and inconsequential spats about my team versus your team. Whether it's a football team, a basketball team, or a political team, social media unquestionably has made these tribal affiliations even more polarizing. Everyone belongs to an affinity group. One of those affinity groups nowadays, for better or worse, is comprised of people who live with chronic illnesses.

I'm not sure whether popular chronic illness memes are effective in conveying the suffering that so many people experience. They certainly may convey that the person who posts them is in some kind of duress, but do they trigger a truly empathetic reaction from the people who view them? Probably not all that often. Why not? Possibly because of human conditioning, if not human nature.

I write a lot about Lyme disease, and as a result, my Twitter account has become a hub of all manner of information related to Lyme and associated tickborne illnesses. Most (all?) of the people who tweet with or to me about Lyme have a personal connection with the persisting form of the disease--in most cases, they live with it, and in some cases it's their children or spouse who lives with it. Either way, they've gone through the mill that the great majority of chronic illness patients go through. For the uninitiated, I will summarize this all-too-common experience:

- A previously well person realizes (often gradually, over years) that she does not feel well.

- This person goes to a doctor, as people do when they don't feel well.

- Her doctor is compassionate and concerned, suspects one or several possible causes of the ailment, and orders blood tests.

- The blood tests come back normal, and the doctor asks the patient whether she has a stressful life. The patient says yes, and the doctor suggests "trying" an antidepressant or anti-anxiety medication. The patient says OK.

- The patient's health continues to decline, although she feels a reduction in overall anxiety. She reports back to her doctor, and her doctor refers her to one or several specialists for further investigation.

- In the case of patients who have Lyme disease--as one example--a neurologist performs a physical examination and observes no abnormalities, or one or two anomalies that warrant further investigation. The neurologist orders brain and spine MRIs and perhaps electromyography, electroencephalograms, and auditory and visual evoked potentials. All the tests come back normal, or one or two anomalies are observed that do not, when taken together, come together as a complete puzzle.

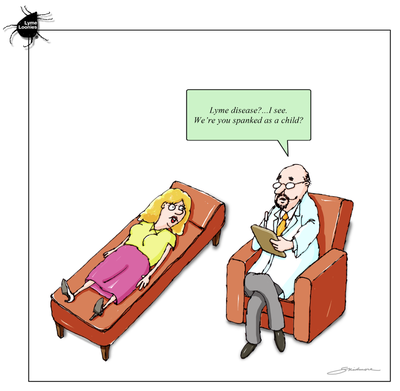

- The neurologist concludes that the patient probably does not have a neurodegenerative disorder, with the following qualifications: 1) it is possible that the patient may be in the early stages of multiple sclerosis and that the causes are simply not yet observable via MRIs, and so if the symptoms become severe (e.g., paralysis, blindness, or loss of bowel control), then the patient should have another MRI; 2) it is possible that the patient may have a non-neurological disease that is causing some neurological symptoms; however, if this is the case, then the neurologist is not qualified to determine this and the patient therefore may want to see, for example, a rheumatologist; or 3) it is probable--according to this hypothetical neurologist who represents many general and specialty physicians--that the patient is experiencing a psychological disorder and requires psychological interventions and medication.

- The doctor bids the patient farewell and wishes her luck, suggesting one last time that she seek professional counseling.

This is a common scenario. In many cases, the patient's health problems become limiting or even partially or fully disabling while at the same time presenting no outwardly observable symptoms and few or no symptoms that are detected by existing laboratory tests.

This scenario represents the experiences of the majority of Lyme disease patients who have contacted me over the past year and told me their stories. It also represents, I was told recently by a former member of a national Lupus foundation board of directors, the experiences of most lupus patients a couple of decades ago. Likewise patients who have chronic fatigue syndrome (now graced with the more legitimate-sounding name of myalgic encephalomyelitis), fibromyalgia, and various other illnesses that aren't obvious to the naked eye or to the average blood screening or MRI. So it goes.

Which brings me to the tweets I woke up to find from last night.

A couple of those who were tweeting have personally experienced the maddening effects of living with an invisible illness that the medical community dismisses, in part due to a pervasive closed-minded dogmatic attitude that every medical condition that exists is already fully understood and written in a medical textbook, and in part due simply to an inability to diagnose (much less treat) an illness that can't be observed. (This is the point at which the Hippocratic oath should kick in and practitioners should carefully listen to their patients' complaints and not default, as far too many do, to an assumption that what isn't observable must be a psychiatric disorder.)

The Twitter discussion in which I had been tagged last night was rather complex, discussing the pathology of the infectious agent that causes Lyme disease in mice.

One person said that mice are immune to Lyme disease.

Another person said that only wild mice are immune to Lyme disease, but certain laboratory mice are not immune to it.

Another person, a medical doctor who contributed to a 2008 review of the Infectious Diseases Society of America's (IDSA) Lyme disease treatment guidelines (*which are outdated and currently being reviewed after having been unlisted from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's federal National Guidelines Clearinghouse in early 2016), said that no mouse species is "immune" to Lyme disease; however, some species of mice can become infected with Borrelia burgdorferi but live asymptomatically, just as some human beings have tested positive for Lyme disease despite experiencing no Lyme disease symptoms.

This discussion caught my attention for two unrelated reasons. The first is tangential to this overall essay, but I will mention it briefly: The federal government and the medical community overall recommend that all sexually active adults should be screened regularly for HIV and for other sexually transmitted infections. After all, if a person possibly could have contracted any acquired infection, then as a matter of both public and personal health, that person should seek medical care, and the diagnosis ideally should be reported to authorities to gauge infection rates. Many patients who have STIs observe no symptoms, yet no doctor would tell a patient, "well, as long as you feel fine, there's no reason to screen you for HIV or syphilis."

And yet, this is the CDC's recommendation for Lyme disease: "Laboratory tests are not recommended for patients who do not have symptoms typical of Lyme disease."

If no laboratory test is ordered for Lyme, then no diagnosis will be made. If a patient has Lyme disease--even if he or she has no present symptoms--that disease will live on in the body. Is that something we really want? I'll leave that question for those in the medical community to answer.

The second reason the discussion of Lyme in mice caught my attention is because--as much as this will make a lot of people's eyes roll--my personal outlook is that non-human animals are also sentient, conscious beings that have their own personal worlds just as every single human being has his or her own personal experiences, sometimes shared with others and sometimes not.

In the case of Lyme disease, as discussed above, in many cases one individual's personal world has been absolutely devastated, with excruciating nerve pain, paralysis, mental confusion, memory lapses, panic attacks, and countless other life-affecting and sometimes disabling symptoms that often escape either direct or indirect observation by medical practitioners. In these cases, there is a great divide: some doctors will admit that a patient may have a severe physical condition that is difficult or impossible to objectively observe. Other doctors will deny absolutely that a patient may have any physical condition that can't be diagnosed with a blood test or body scan--period.

Patients with a great number of chronic diseases know that these diseasescan be "silent" or "invisible" in this way. Some Lyme patients have visibly swollen joints that cause severe joint pain. Some Lyme patients have severe joint pain with no visibly swollen joints.

Is one patient imagining symptoms and the other experiencing a legitimate health problem? The answer to this question depends to whom you pose it. From my experience, both of these patients' complaints should be taken seriously, and physicians should at least consider that medical science is always evolving and that everything that may one day be understood is not already understood at this moment.

As for the lab and wild mice alike--many are said to host Lyme disease but remain entirely asymptomatic. Those that are considered symptomatic display obviously swollen joints; those that don't have swollen joints are said to live with Lyme disease totally unaffected.

The problem with this assumption is that it is, in my estimation, a pretty bold and arrogant assumption. Mice don't have any way to voice their complaints. They don't have a vocabulary with which to process their thoughts or with which to convey their experiences to other individuals, and particularly to any individual of an entirely different species. And even if they were able to do this, it is an absolute given the way many Lyme disease and other chronic disease patients are treated, that any non-observable complaints they may have would be entirely dismissed by researchers and doctors.

I'm not suggesting that some mice (or human beings) may not be infected with Borrelia burgdorferi and never experience the illness of Lyme disease as a result. There are many known cases of "carriers" of infection who don't fall ill--they harbor infectious diseases but don't suffer from them.

What I am suggesting is that just as we often use laboratory animals as living metaphors for human health, we should be more thoughtful about what we consider to be "asymptomatic" in non-speaking animals as a result of what we know about invisible illnesses in human patients. When so many people are limited and disabled by illnesses that are not observable--no swollen joints, no visible scarring on brain scans--then we should consider the real possibility that an "asymptomatic" non-human animal may be a diseased individual with no outwardly observable symptoms.

This more empathetic view could have profound implications on the investigation of diseases among animals or within non-human laboratory subjects. If we adhere strictly to the if-we-can't-see-it-it-doesn't-exist paradigm, then we may be arrogantly self-limiting our medical investigations, both in the laboratory and in the doctor's office.

We should never forget that there was a time at which we thought everything we could see with the naked eye was all there is to the human body. With the advent of microscopes, we discovered cells and pathogens. With the advent of X-rays, we discovered the ability to see through flesh. With the advent of magnetic-resonance imaging, we discovered the ability to map the brain, and then with fMRIs, to map brain activity. These technologies have led to the discovery of countless causes of illness that we never would have understood--and some of which we would have arrogantly denied exist--had they not been invented.

The "invisible illness" meme is so prevalent on the Internet because the phenomenon of invisible chronic illnesses is a real one, and it's so traumatic that people resort to passive-aggressive, desperate interpersonal communications in the form of Internet memes.

We primarily use our eyes to diagnose illnesses and to interpret findings of laboratory reports. Mice can't tell us how they feel, but people can. If a mouse has a sore throat, we will never know it because we would never look inside a mouse's oral cavity for no good reason, and a mouse can't say "ugh, it hurts to swallow." If a person has a sore throat, we can recognize the signs of discomfort on his face because we can read the emotions of our own species, and because he almost certainly will tell us that his throat hurts. His words, then, are a reliable diagnostic tool that helps us to determine what we could never even suspect might also be occurring in the world of a mouse. This doesn't mean that the mouse cannot have a sore throat; it means that that sore throat is imperceptible to us, and that the mouse's sore throat could in this hypothetical scenario be an unperceived indicator of an zoonotic illness that could jump from a mouse species to homo sapiens. Maybe we should consider alternative means of observation that aren't already common practice.

We need to start using our ears as much as we use our eyes, and we need to understand that patients' desperate pleas for help and persistent reports of illness are diagnostic indicators as valid as pictures of broken bones and laboratory write-ups of complete blood counts.

Despite the arrogant confidence our species places in the technologies of its own creation, in some cases our organic bodies are equipped with sensors far more sensitive than man-made laboratory equipment and third-party reviews of photos of brain tissue.

To dismiss patients' words is akin to throwing away a report from the most sensitive diagnostic technology that has yet to be invented. A little respect and a lot more empathy would go a long way in advancing medical research and practice.

This has been my version of an invisible illness Internet meme. It all boils down to the same thing: believe me, this is real and it is serious, and I need you to know that because I never expected to be in this position--and I know you don't either. Just in case it does happen to you, wouldn't you want to be taken seriously?