Liberal arts colleges teach many valuable skills, but collaboration is not often among them.

This is curious, because virtually all human activities involve collective behavior. A conversation, or an Op-Ed such as this, takes at least two to tango (or tangle, as the case may be). On a much larger scale, the electric companies that power my computer in New Hampshire, where I work, arise from immense cooperative activity. As UCLA anthropologist Alan Fiske argues, "The most striking characteristic of Homo sapiens is our sociality."

A liberal arts education strives to teach students "critical thinking." And rather than narrow technical competencies, students in the liberal arts ideally develop "writing, researching, quantitative, and analytical skills."

However, in my view, our liberal arts curriculum doesn't foster collaboration.

At Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., I teach, among other courses, a number of small, interactive seminars in my Department of Film and Media Studies. In discussions with me and one another, students hone their thoughts and opinions. But beyond that, it's all about personal accomplishment.

I grade each student individually. This, needless to say, is the nationwide standard. As a result, liberal arts undergrads too often end up thinking of themselves as solo agents, obsessing about grade point averages, and pitting themselves against their classmates.

Instead, I believe, they should steal a page from Tina Fey's advice on improvisation: listen; agree and add something; make positive statements; and learn that there are no mistakes, only opportunities.

They need to think of classwork as collaborative improvisation, as a stage where they make up the scene on the spot. It is not for nothing that improv is being taught at graduate business schools.

My own learning on cooperation and communication deepened while directing and producing Still Moving: Pilobolus at Forty, a documentary about the Pilobolus Dance Theatre.

The Dartmouth-born troupe, established in the 1970s, has refined collaboration to a fine art. During its first decade, the company undertook an experiment in democratic artistic production. The six members improvised works together. There was no "decider."

Such true collaboration is still looking for a toehold in the liberal arts curriculum.

Meanwhile, scientific researchers have become phenomenally collaborative. Scholars are teaming up across international boundaries. The two-decade project to sequence the human genome involved researchers from more than 20 institutions in six nations.

However, despite their own practices, as a rule, professors of science do not teach collaboration. At Dartmouth, the exception proves the rule: Laboratory in Psychological Science, a course required for the psychology major, obliges students to "jointly design, conduct, analyze, and present their research projects" for group grades, as Psychology professor Jay Hull told me.

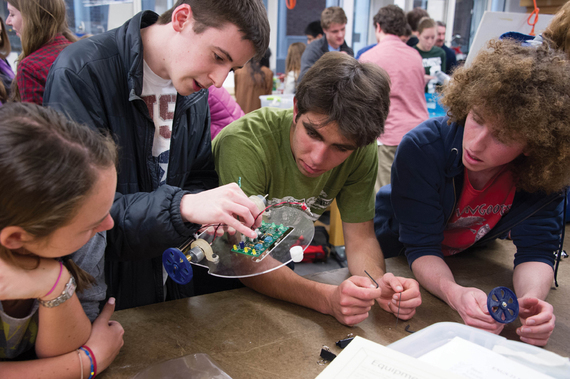

As elsewhere, such truly collaborative courses remain a tiny minority. The most renowned in Hanover may be Introduction to Engineering, a course the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth has offered for more than 45 years. In this hands-on class, undergrads work in teams of four to design original inventions that address real-world problems. Projects are graded collectively.

Yet, very few undergraduate courses demand such collaborative engagement.

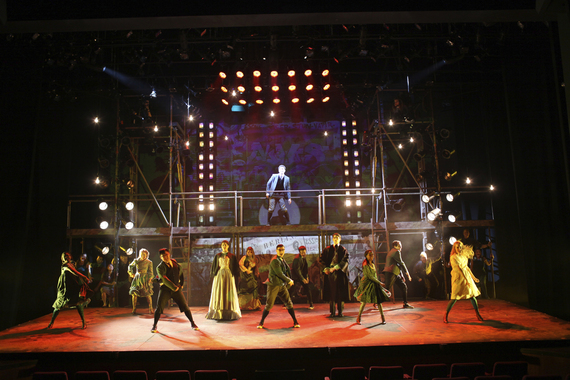

On the Dartmouth campus, the most collaborative curricular endeavor may be MainStage, a production by the Department of Theater.

Four to six faculty members, numerous staffers, and hundreds of undergrads annually bring intellectual and creative muscle to stage a professional play or musical. Individual students take pride in participating, in ways large and small, in something greater than the sum of its parts.

Similarly, the Department of Theater offers a course in Creativity and Collaboration, topics that its website tellingly notes are "rarely taught."

Anyone who watches the never-ending credits of a Hollywood movie knows filmmaking is an intensely collaborative activity. Inspired by the MainStage theater enterprise, I recently created a Group Documentary production course. Students, several staff members, and I work together to make a professional documentary in a 10-week term.

The class gives students hands-on experiential learning in filmmaking, which includes constructing narrative and character, mastering the techniques and aesthetics of image and sound design, and making effective arguments through editing, all abilities culled from the liberal arts.

Fundamentally, however, Group Documentary is a course in collaboration. In an evaluation, one junior wrote: "FILM39 is unlike any class I've taken. It's a nice change from the atmosphere of an exam-based course. Instead of competing with one another for the highest score, FILM39 requires us to coordinate together to achieve the best possible final product."

In the past three years, students have directed documentaries about a bear cub rescuer, a feminist comedian, and a gay, African-American choir director.

But this is not to say that collaboration is easy. Students have to find constructive ways to disagree; criticism doesn't always move the project forward. Plus, some team members slack off and others do more than their share. It's uncannily like the real world.

Outside these rare exceptions, where, during their college years, do undergraduates learn how to collaborate intensely? In my experience, only through "extracurricular activities."

These would include orchestra, singing groups, and, especially, team sports. Such activities encourage students to develop interpersonal abilities, emotional intelligence, empathy, trust, and working with others (whether they like each other or not) on behalf of a greater goal. "Sports teach workplace values like teamwork, shared commitment, decision-making under pressure, and leadership," says Jennifer Crispen, a professor at Sweet Briar College.

However, at liberal arts colleges, unfortunately, these activities remain "extra" instead of "curricular." We need to teach collaboration, because, as science writer Steven Johnson argues, good ideas and major inventions come from connectivity, borrowing, collaborating, and networking.

I attended Cornell as an undergrad, in part thanks to my soccer skills. I did graduate studies at Temple and the University of Iowa, important public institutions. Afterward, I taught at Vassar and Middlebury, well-regarded private colleges.

But little that I saw at these institutions over the past 35 years suggests they educate undergraduates -- inside the classroom -- to collaborate successfully on group projects. I'd love to be proven wrong about this, because, as psychologist Daniel Goleman concludes, "emotional intelligence" helps make for the most successful careers.

In Norwich, VT, my daughter's public elementary school offers day-long team-building exercises, which required her to cooperate with, among others, "a bunch of rambunctious and unruly kids" (her words). But collaborating doesn't stop after K-12 education; it should continue in college courses.

So, how can we encourage team-building through our teaching? In addition to critical thinking, could we agree that collaboration, in the strong sense of the term, ought to play a greater role in the liberal arts curricula of our colleges and universities?

As Pilobolus co-founder Michael Tracy told me about studying in Hanover in the early 1970s: "I discovered that dance had all the physicality of sports, without the broken knees and the killer instinct. Dance was about creating imagery cooperatively. We were being physical, but it was not to destroy the other team, it was to create something together in a collaborative way."

A liberal arts education still best provides the skills in thinking critically that our rapidly changing society demands. Ideally, it also instills in undergraduates a lifelong love of learning.

But in addition to critical thinking, liberal arts students need to learn how to act in the world, to improvise, to play together, to collaborate and, in the process, to make each other better.

(This article was originally published in The Conversation.)