If you ever want a good laugh, I highly suggest looking through the Google Analytics of yourself, to see what advertisers think of you. For example, mine says that I'm an 18-24 year-old-woman interested in politics and pop culture. The ads I usually get are to buy new seasons of House on DVD, to volunteer for Obama for America, and for some reason, to sign up for Christian Mingle (the Internet is now my mother).

The Analytics determine this based on the material you view online. It tracks what websites your IP address visits most often and a quick description of what those websites cater to. This tracking allows advertisers to find you where you live online and tailor their advertising campaign to their target audience.

A potential wrench in this plan, however, is an emerging "Do Not Track" option on web browsers and websites.

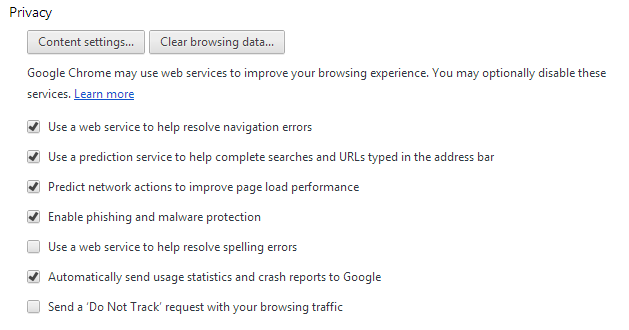

According to the World Wide Web Consortium, The Do Not Track option has been on some, but not all, web browsers for a few years now as a default, an "opt out" rather than an "opt in," and a quiet option that most web users ignored. But now to comply with White House requests for more Internet privacy and consumer protection, major web browsers like Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, Apple Safari and Microsoft Internet Explorer will now be including a "Do Not Track" option as an opt-in preference - with Google being the last to jump on the bandwagon in adding the privacy setting to Chrome. They're not just adding the option, though, they're promoting the change and making users aware that the option even exists. In the new version of browsers (this screenshot is Mozilla Firefox), the option should look something like this:

The idea of this software is to prevent the Internet "big brothers" from accessing personal information about the Internet users, and to stop following them around the Internet with obnoxious pop-ups and analytics-targeted ads. While it doesn't stop people from "geotagging," or locating where an IP address is coming from, it does stop them from storing personal information based on past Internet history and preference -- at least, from the browser end.

The move could limit how advertisers reach their potential consumers, and may have an effect on pay walls and sponsored websites. It could also limit how political candidates campaign as well.

As I said before, "geotagging" seems to be unaffected by the change in privacy settings, so local candidates can breathe easy knowing their voting districts will still be easy to identify online. Similarly, the Do Not Track option doesn't seem to interfere with the ability to e-mail and fundraise this way.

What would change is the ability to find what sites a constituency frequents, and where best to advertise to that constituency to get the most coverage for the investment.

For example, if a progressive candidate was planning to campaign to college students regarding their plan for increased scholarships and grants; they would be able to geotag 18-24-year0olds within their district boundaries. They would be able to e-mail them regarding their plans and ask for campaign donations to make that plan happen (although we all know college kids have no money). They would not be able to see which websites these voters frequent, they would not be able to easily tailor an online ad campaign towards this group - and they would not be able to determine which websites would best serve as hosts for online campaigning.

All of this change will mean nothing, however, if websites do not agree to stop tracking users. Some, like Twitter, have already elected to cooperate with the Federal Trade Commission in agreeing to not track web users by their web's cookies. Facebook released a statement in 2011 regarding the Do Not Track movement, saying:

"We are very pleased that the leading online trade groups are about to endorse the use of the Mozilla "Do Not Track" header as a way users can indicate they don't wish sites to track them to tailor banner ads at other sites...Don't get us wrong, we like our ads to be more relevant. But we want users to have transparency and control over what is happening, so that the atmosphere for trust can be restored. If users trust the sites they visit, many will value efforts to provide a more relevant experience."

This is misleading, however, because Facebook does still track users through Facebook Connect and the "like" button on other sites -- anytime a user logs in using their Facebook as an option (for example, sharing an article on Huffington Post), they are still tracked even though they're not on Facebook's website.

At this point, the Do Not Track opt-in option will be a part of the major web browsers by the end of this year; when websites will follow suit is a far different story and may take months or years to happen. So for now, advertising and campaigning will continue using online analytics and user preferences to determine where best to place ads. But this is a burgeoning online privacy issue, and we as progressives must evolve our campaign strategies to reach our constituents without raiding their cookies and invading their online privacy to do so.