It's time to eliminate the so-called collateral consequences of criminal convictions -- the known and unknown penalties that follow people convicted of crimes, sometimes for the rest of their lives. The American Bar Association has compiled a national list of 38,000 collateral sanctions that people involved in various ways with the criminal legal system face on top of their court mandated sentences. There are more than 2,200 such penalties in New York state alone, extending to nearly every facet of daily life -- employment, licensers, property rights, contracts, citizenship, education, voting, housing and family or domestic rights.

In many cases these collateral consequences -- blanket legal prohibitions and extra-judicial penalties -- are more severe than the initial criminal sentence that provoked them and grossly disproportionate to the charged offense. A complete picture of the ramifications of these policies is impossible to quantify because the indirect damage ripples out to entire neighborhoods and is then passed down from generation to generation. The direct consequences are clearer. A disorderly conduct violation for spitting or jaywalking -- not even technically crimes -- can trigger a two-year ban from public housing in New York City. A misdemeanor can leave a person ineligible to volunteer with mentoring programs, and comes with a mandatory ban from even the most benign activities such as conducting bingo games. Any felony conviction triggers a discretionary ban from receiving a barber's license and a mandatory ban from earning a real estate broker's license. Veterans lose their right to annuity from the conviction of a single misdemeanor. City employees can lose their job based solely on an individual arrest, not even a conviction.

The Attorney General of the United States, Eric Holder, acknowledged in 2011 that many of these collateral consequences serve no public safety function. He also asserted that reducing the additional social harm created by these penalties would promote "safer and healthier communities, assist individuals released from prison and jails become productive citizens, and save taxpayer dollars." He has made his office available to state governments as a resource to facilitate the repair of what he has termed "failed reentry policies." And yet, there appears to be little urgency from government actors to rectify these problematic and unnecessary laws and city codes.

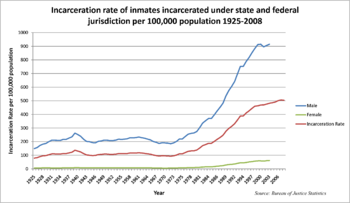

During the past forty years, the number of people subjected to these penalties has risen astronomically as a result of policy changes that have prioritized the increased use of retributive punishment, custodial arrest and incarceration as a means -- misguided though it may be -- to resolve social conflicts. The results have been staggering and have led more than one observer to describe what we commonly refer to as the criminal justice system as a human-rights crisis. During the past four decades, the incarcerated population of the United States has risen by 600 percent and now includes more than 2.2 million people. An additional five million people remain under government control through programs, such as probation and parole. 65 million U.S. residents have a criminal record of some kind. Almost nine percent of the population -- 19.8 million people -- has a felony conviction. Each year there are nine million people going through the doors of local jails and 700,000 more are released from state and federal prisons. In 2013 there were more than 90,000 arrests in Brooklyn alone. Of the 14 million arrests nationwide in 2009, just four percent were for violent crimes -- the vast majority being low-level misdemeanors and violations.

These statistics could be worse. Research shows that nearly every adult has committed a crime at some point in their life; however, due to the quirks of law enforcement, most people escape detection and thus any long-term legal consequences of their actions. Most of these people go on to law-abiding, socially constructive lives; entanglements with law enforcement, rather than any initial rule-breaking, may be more predictive of future problems. At a recent event in New York City, a state legislative staffer explained that smoking marijuana as a teenager had not ruined his life -- an arrest might have, he continued.

The scrutiny of law enforcement, particularly in urban environments, falls disproportionately on a handful of neighborhoods, which are becoming more and more segregated by race and class. More than 75 percent of people held within the prison system in New York comes from a small handful of neighborhoods in New York City. Of course, the entirety of our so-called criminal justice system operates in such a way that people of color and those cut-off from social and economic resources are most likely to suffer the burden of collateral consequences -- a result that has led Civil Rights Attorney Michelle Alexander to describe this mosaic of civil penalties as the New Jim Crow. This racial disparity has led the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to warn against discriminating against potential hires because of past criminal convictions because such a policy will inevitably lead to racially biased practices.

Many consequences of arrest set in immediately as even short-term confinement can lead to job loss, eviction and other harms. The difficulties of showing up to court month after month to contest even minor criminal charges -- or the inability to afford bail -- often coerce people to accept plea agreements solely to resolve their case as quickly as possible. This is one of the major reasons that just two percent of cases in New York City actually go to trial. The costs of missing work, missing school, finding childcare, carfare and so on are too great for many people to withstand. Unfortunately, because the extensive civil consequences of taking plea offers are often unknowable to participants in the case, it is impossible to account for all of the negative implications. The consequences of this decision can last a lifetime.

As of 2012, most states allowed hiring decisions to be based on arrest alone. The increasing use of criminal background checks, which are notoriously inaccurate, has made finding a job harder for deserving applicants. Meanwhile, research has shown that jobs, housing and benefits are the very things that help them to stay out of prison. A steady job, not the threat of incarceration, has been shown to be the most effective deterrent to crime. Thus, employment discrimination remains one of the most noxious collateral consequences and also provides, perhaps, the most obvious target for excision. Two highly regarded studies by Devah Pager showed that employment applicants with a criminal record were far less likely to be brought back for an interview than their otherwise similarly situated counterparts. Employees have even fewer protections in firing, however.

According to the New York State Bar Association, approximately 60 percent of formerly incarcerated people are unemployed one year after release, and 80 percent of people who violate the terms of their parole are unemployed at the time of the infraction. There are more than 500,000 arrests in New York State annually, and nearly seven million adults in the state have a criminal record. Employment bans based on criminal records could be a mainstream labor issue. Opening pathways to employment will help not only former arrestees, but their neighborhoods and, more broadly, our national economy. In terms of gross domestic product, the reductions in employment caused by employment bans for formerly incarcerated people cost the U.S. economy between $57 and $65 billion in lost output every year.

Employers are rightfully concerned about the background of the people they hire and the risks potential employees might pose to their business's bottom line. Many sectors, such as banking and security, have bans for people who have been convicted of job-related crimes such as fraud or weapons charges, for example. These rules could stay on the books. But research has begun to test empirically the fears that employers have about hiring people whose criminal records have nothing to do with the tasks required by their potential employers. Blumstein and Nakamura's 2009 "Redemption Study" showed that after staying clear of the law for between three and eight years, people with criminal records were indistinguishable from the general population in terms of risk for future criminal arrests. If this is truly the case, how might we be able to swiftly bring at least this group back to full citizenship? Expungement of criminal records following periods of good behavior would appear to be essential.

Over the past few years, state lawmakers have been making gains toward reducing the damage caused by collateral consequences and better informing criminal defendants as to the rights that they are giving away over the course of their cases. Some of these penalties -- such as immigration consequences, housing bans and voting rights -- are well-known to public defenders, district attorneys and judges, but others are not. Although immigration consequences may seem obvious today, it was not until 2010 that the provision of counsel as to the immigration consequences of a guilty plea was institutionalized. The Uniform Law Commission has drafted the Uniform Collateral Consequences of Conviction Act (2009), which would provide for the collection and notification of all collateral consequences at critical times during criminal cases. The law would also require that collateral consequences be authorized by statute. So far the entire bill, which has been introduced in New York, has not gained sufficient traction in any jurisdiction, but North Carolina has passed a very limited version of the suggested changes.

The attorney general of the United States has said that many of these civil penalties serve no public safety purpose at all and that many actually create the conditions that are most prevalently associated with crime, such as joblessness. What -- besides senseless devotion to a broken system -- is holding us back?