Dieting. By now everyone accepts that this is a fundamental, if dreaded, foundation for weight loss and health. But a surprising recent development in dieting research indicates that, at least for cardiovascular disease -- the No. 1 killer of Americans -- it may be time to ditch the diet.

This may sound like good news to anyone who has ever dieted, but it was startling news to dieting researchers. The National Institutes of Health reported last month that their large dieting study had to be ended two years prematurely because it found no differences in cardiovascular health between participants in a strict diet and exercise program and those in a control group.

The scientific community had been waiting for the results of this study for a long time, because this was no ordinary trial. This was the "Look AHEAD" (Action for HEAlth in Diabetes) trial led by eminent researcher Rena Wing. With its rigorous design and strict low-calorie diet, it had accomplished what other trials of this magnitude had not: Participants in it had been successful at their diets for four years.

The three of us know how rare this is. Our careful review of the research on dieting left us ready to shut the door on further dieting research, because it so seldom leads to sustained weight loss. We analyzed the 20 most rigorous tests of low-calorie, low-fat, or low-carbohydrate diets that looked at how much weight people kept off for two or more years. According to these randomized controlled trials, which are the gold standard form of evidence for any treatment, the average amount of weight loss maintained by dieters for at least two years didn't even reach two pounds.

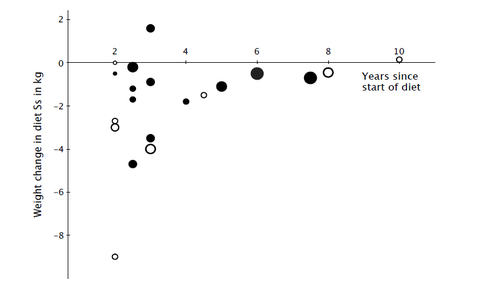

Average weight change among diet subjects in 20 studies by length of follow-up.

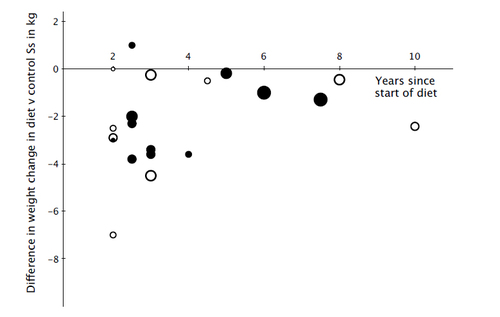

Average difference in weight change between diet subjects and control subjects in the same studies by length of follow-up. The size of the symbol (from smallest to largest) indicates the starting sample size: under 100, under 200, over 200, over 1,000, and over 10,000. Solid circles indicate that less than 20 percent of starting sample dropped out of the study. Open circles mean 20 percent or more of the starting sample dropped out.

But whenever we tried to convince other researchers that dieting was not the solution, our colleagues would say, "But what about the Look AHEAD trial?" Unlike the dieters in the studies we reviewed, dieters in the Look AHEAD trial (all of whom were overweight or obese and had Type 2 diabetes) did in fact lose weight and keep it off. They managed to sustain a nearly 5 percent weight reduction for four years. As long as the Look AHEAD trial was out there, we couldn't convincingly say that dieting does not work.

And if dieting does work, if we can get people to lose weight and keep it off, researchers have argued, then we should see multiple cardiovascular health benefits. The Look AHEAD trial, therefore, was to be the long-awaited test of whether successful dieting truly promoted better cardiovascular outcomes -- and the answer, unfortunately, was no. Although the trial led to improved quality of life, decreases in sleep apnea, reduced need for diabetes medication, and delayed physical disability, it did not achieve its most important objective of fewer strokes, heart attacks, or cardiovascular deaths.

Why didn't successful dieting and exercise lead to better cardiovascular health? We can't speak to the puzzling role of exercise here, but based on our expertise in dieting, we think that the explanation may be very simple: The definition of "successful" dieting is flawed.

Let's look closely at the definition of successful dieting. The Institute of Medicine considers a diet successful if people lose just 5 percent of their starting weight and maintain that weight loss for a year. A 200-pound woman, for example, would need to lose only 10 pounds and keep it off for a year to be considered a successful dieter, even though this amount of weight loss won't make her thin, nor is it even likely to move her down a dress size. This standard is not only remarkably lax but has no medical rationale.

If this definition sounds as strange to you as it does to us, you should know that this was not always the case. The original standard recommended by physicians was arbitrary, but you would be hard-pressed to call it lax. It was based on the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tables, which require particular weights for each height and body frame size. A medium-framed woman of average height (5 foot 5 inches) was expected to weigh about 134 pounds, and a diet would only be considered successful only if she reached that weight. The trouble is, obese dieters rarely met that goal, as it required a very large weight loss (at minimum, 46 pounds for that 5-foot-5-inch woman).

In the absence of more effective diets to recommend, researchers simply changed the definition of success. Their new standard was to lose 20 percent of one's starting weight. However, a review of diets from that era found that only 5 percent of obese dieters succeeded even by that definition. The solution? Change the definition again.

Eventually, the medical community settled on the current standard of losing just 5 percent of one's starting weight, despite having no scientifically-supported medical reason for doing so. As a result, dieters can be deemed successful without achieving notable amounts of weight loss or, as in the Look AHEAD trial, meaningful improvements in cardiovascular health. And remember that the majority of dieters do not even lose enough weight to meet this ineffectual standard.

We fear that researchers will now advocate a stricter standard for dieting success in the hope that a larger amount of weight loss will lead to these cardiovascular improvements. Of course, a stricter definition did not result in more weight loss in the past, and it won't do so now either. It may finally be time to acknowledge that dieting is not the panacea we hoped it would be.

A. Janet Tomiyama is assistant professor of psychology and director of the Dieting, Stress, and Health Laboratory at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Britt Ahlstrom is manager of the Health and Eating Laboratory at the University of Minnesota.

Traci Mann is professor of psychology and director of the Health and Eating Laboratory at the University of Minnesota.

For more on diet and nutrition, click here.