Slate and the New America Foundation recently sponsored a conference on Aging. At the conference Professor S. Jay Olshansky spoke about his proposal, outlined in his Slate article A Wrinkle in Time, for using 1% of Medicare monies to sponsor research to slow the aging process.

Quality of life is a BIG component of whether longevity is a good thing. This is why longevity is characterized in literature as the "Fountain of Youth." Olshansky's thesis is simple. If we don't slow down the aging process, our ability to mitigate disease will leave us with a growing older population requiring more care (i.e., more costs).

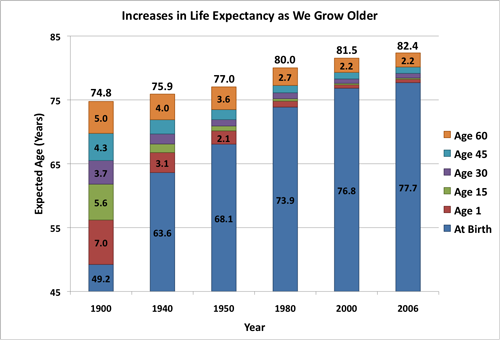

Before getting to the heart of the matter, I think it would be useful to look at how far we have come over the last century since longevity is in someways very different than treating diseases. For most of our existence, it was been childhood diseases that did us in. At the beginning of the last century our life expectancy increased 7 years if a newborn made it to age one (see graph). Another 5.6 years were added at age fifteen and 3.7 years if young adults were lucky enough to reach age thirty. So a newborn had a life expectancy of 49.2 but a 30-year old had a life expectancy of 64.5. If you made it to 60, then your expected life span was 74.8 years. Back then 60 years of age was a BIG "if."

We have clearly come a long way since 1900. By 1940 a newborn's life expectancy was 63.6 years and it jumped to 68.1 years after World War II with the availability of Penicillin. It took another 30 years (e.g., 1950 to 1980) to add another 5 years to a newborn's life expectancy (73.9 years). All the advances in medicine, and environmental/health regulation in the last 26 years (e.g., 1980 to 2006) has added less than 4 years to a newborn's life expectancy and less than 2.5 years to the life span of anyone lucky enough to reach 60.

When I was listening to Olshansky talk about the subtle difference of discovering treatments for diseases (i.e., the last 50 years) versus slowing aging, it became clear that we needed to consider strategies to bring drugs to market quicker or more efficiently ways of expanding our thinking about how drugs come to market. As Olshansky points out in his article, we are at a point of diminishing returns when curing the major diseases. If we cure cancer, it extends life about 3 years because other competing diseases will begin to impact us.

There is no question that social equity issues such as poverty and access to medical treatment affect life expectancy. The same is true with our life style choices (e.g., eating, exercise). Yet the precise benefit often is elusive as is the case for alcohol where epidemiological studies find surprisingly contradictory results. So, what happens when we throw FDA into the brew?

We have a system of FDA approval that requires a pharmaceutical company show three things: (1) a mechanism of action (i.e., identify why a drug works), (2) safety and (3) efficacy in managing a measurable biologic end point associated with a disease. This last condition is a problem.

Look at the conundrum You're a researcher and you walk into FDA one day and say: "I have in this bottle an elixir that if taken every day of your life will add on average 4 years to how long you can expect to live." FDA says: "What disease will it cure?" The researcher says: "It won't cure disease, it will postpone or mitigate the lethality of some diseases, but as you get older you will get other diseases." FDA then hopefully says: "We get it. While we do not now nor have we ever thought about age as a disease metric, we accept the concept. All we need to do is test your drug on a sufficiently large population and for a long enough period of time to prove to us it works." That is the problem.

My question is not whether Olshansky's goal is worthy (It is). The biotech industry is strewn with startup companies that discovered mechanisms of action that academics, investors, and Industry thought might mitigate aging. Yet, these companies' candidates ultimately did not control or cure a specific disease in a clinical trial. Longevity research is aimed at postponing, not curing disease. How do we now go back and test these drugs to see if they postpone the onset of disease? My question is how will we refocus our thinking and research on non-disease endpoints that will undoubtedly be more personalized and without the crisp dichotomies that exist when looking at a single disease?