For a few balmy months in the summer of 2015, the U.S. presidential election was beginning to look like a contest that would lead either to the second coming of President Clinton or to a third President Bush. While the then-front-runners were favored by donors and the party establishment, the prospect of a dynastic clash had unsettling undertones: With the exception of Obama's two consecutive terms, the United States has been led by either a Bush or a Clinton since 1989. Many of their key appointees at the departments of state and defense and within the inner circle of the White House have dominated Washington politics even longer, and have circulated through high government posts since the Nixon administration of the early 1970s. Beltway elites persisted through the periodic swings of the electoral pendulum.

Hence the queasiness: The prospect of prolonged dynasties seems hard to square with the ideal of a democracy "of the people, by the people and for the people." It brings to mind the warning words of Alexis de Tocqueville, who had counseled in 1835 against the gradual diminution of the electorate into "a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd."

But as historians like Lawrence Goodwyn have argued, this dynastic tendency is no anomaly. American politics has long been dominated by an elite that has successfully insulated itself against the whims and tides of public opinion. During the first American presidential election in 1789, seven of the 13 original colonies did not even allow a popular vote but simply appointed delegates to the Electoral College. Political parties did not yet exist. Indeed, the founding fathers were distrustful enough of organized parties that they expunged any mention of them from the draft of the Constitution. When parties first entered the American political landscape in 1796, they served as lobbying groups for the presidential bids of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, not as vehicles of mass expression. "Representative democracy" originated and blossomed in the United States as the representation of the interests and dispositions of a rather small sliver of the American population.

Since those early days, political participation has often remained a minority phenomenon: After peaking in the 19th century, voter turnout rates have hovered around 55 percent for presidential elections at around 40 percent for midterm elections for much of the 20th century. Party affiliation is at an all-time low. The expansion of the franchise and the introduction of the primary system have changed the ostensible procedures of democracy, but have retained the influence of party elites in the form of super delegates and through control of the allocation of campaign funds. Elite politics -- prominently derided by Walt Whitman as the "never-ending audacity of elected persons" -- is a feature of the American political system, not a bug. Voters seem to have tolerated this system with a slightly disgruntled shrug: Congressional approval rates are notoriously low, and have stayed well under 40 percent for many of the last 40 years.

Almost as persistent as elite democracy is the debate over its merits. In 1911, the German sociologist Robert Michels posited what has become known as the "iron law of oligarchy." Michels argued that concentrations of power and elite dominance are inevitable features of mass organizations like political parties. As the size and complexity of an organization increase, power becomes concentrated within a core group of leaders. But instead of acting as "servants of the masses," these bureaucratic and political elites establish monopolies of information, and dominate over the apathetic rank-and-file. Several decades later, the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter had an even more dire view of politics:

The typical citizen drops down to a lower level of mental performance as soon as he enters the political field. He argues and analyzes in a way which he would readily recognize as infantile within the field of his real interests. He becomes a primitive again.

For Schumpeter, the significance of elite politics was found not in its inevitability but in its necessity: Only through the considered judgment of elites could the "unintelligent and irresponsible" proclivities of the masses be contained. Schumpeter had witnessed the dark and anti-Semitic underbelly of mass fervor in Austria and Germany in the 1920s and 1930s, and had come to embrace rule by an enlightened elite as the best guarantor of political and economic liberalism. In the United States, his concerns were echoed by the likes of Walter Lippmann, who dismissed public opinion as the consequence of emotional infatuation and stereotypes, and argued that complex decisions and calculations were best left to a trained professional elite. The world of mass politics was to remain separated from the world of governance. The tragedy of democracy, Lippmann argued, was the pretense of popular participation: By positing a direct and intimate link between people and politicians, it misconstrued how the system worked in practice.

Only in the 1950s did the tide begin to shift. Building on the work of American progressives like John Dewey -- who had famously declared that "democracy and the one, ultimate, ethical ideal of humanity are to my mind synonymous" -- C. Wright Mills rose to public and intellectual prominence by deriding the presence of a "power elite" in American politics. By turning politics from a matter of public engagement into a practice of rational administration, Mills argued that this elite had not only begun to wield unprecedented power but had also corrupted the basic operations of democracy in America.

The significance of elite politics was found not in its inevitability but in its necessity.

Only against this background of elite democracy is it possible to disentangle the meaning and significance of the specter that is haunting the current primary season: the specter of populism that has seemingly buoyed the candidacies of Donald Trump, Ted Cruz and Bernie Sanders -- three men who don't usually trod the same ground or find themselves fighting from the same corner.

Daniele Albertazzi and Duncan McDonnell, two authorities of the topic, define populism as an ideology that "pits a virtuous and homogeneous people against a set of elites and dangerous 'others.'" This is a useful starting point, for it highlights a crucial aspect of populist politics: They proceed through the drawing of boundaries, the building of alliances and the kindling of the imagination, and thus constitute a political project rather than an individualistic reaction to injustice or destitution.

Populism gathers steam when discontent becomes the spark of political mobilization, when individual grievances are revealed as shared frustrations and when the dispersed energies of the street are cajoled and channeled into collective action.

History's most fervent populists were usually not the Tom Joads of this world, who hunkered down, trekked westward, and worked themselves into early and dusty graves when life threw drought and famine upon them. Populism, like other social movements, gathers steam when discontent becomes the spark of political mobilization, when individual grievances are revealed as shared frustrations, and when the dispersed energies of the street are cajoled and channeled into collective action. That's one reason why populist movements, despite their anti-elitist tones, sometimes cohere behind strong and charismatic leaders. The populist strength is not of a military or financial kind, but is instead rooted in the combination of plentiful bodies and powerful rhetoric.

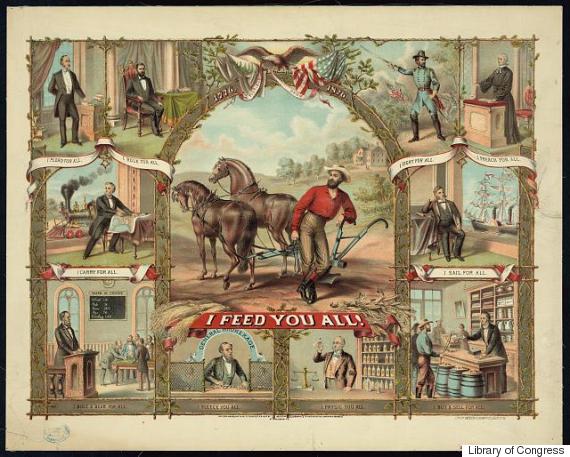

We know all this because populism, like elite politics, has a long history in the United States. One of the country's most significant -- and most understudied -- political mass mobilizations occurred in the 1880s and 1890s, when scores of cotton farmers, sharecroppers, and landowners banded together against "Washington elites" and industrial capitalists. Worried about their declining relevance in a modernizing economy and about the crop lien system that underpinned much of American agriculture, they formed the Farmers' Alliance to "unite the farmers of America for their protection against class legislation and the encroachments of concentrated capital." As the writer Mary Elizabeth Lease noted at the time, farmers needed to "raise less corn and more hell."

Not all populisms are created equal.

Soon, rural activists were calling for the nationalization of railroads, agricultural debt relief and the establishment of cooperative stores. Those stores, they argued, could function outside the regular market economy and thus escape the predatory grasp of East Coast financiers and remedy the regulatory lethargy of East Coast politicians.

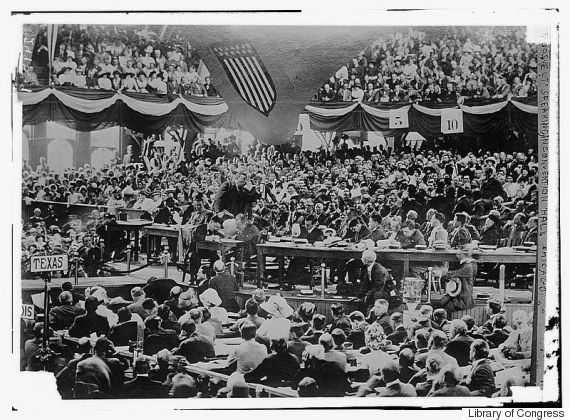

By the 1890s, the increasing circulation of mass media, a vibrant rural lecturing circuit and series of droughts had galvanized populist sentiments and contributed to the formation and early electoral success of the newly formed People's Party. Populist state politicians and congressmen soon broadened the scope of their arguments, and began to link calls for agrarian revival to condemnations of the gold standard and the Federal Reserve. But their influence was temporary. By the early 20th century, agrarian populist energies had dissipated or had sometimes taken ugly turns. Thomas Watson, who first rose to prominence within the People's Party before becoming a voice of demagoguery, could thus declare to applause in 1910 that:

The scum of creation has been dumped on us. Some of our principal cities are more foreign than American. The most dangerous and corrupting hordes of the Old World have invaded us. The vice and crime which they have planted in our midst are sickening and terrifying.

Who was to blame for this preponderance of vice? "The manufacturers," said Watson, who "wanted cheap labor; and they didn't care a curse how much harm to our future might be the consequence."

This highlights another crucial aspect of populist politics: It includes as much as it excludes. Notably absent from the ranks of the People's Party were black sharecroppers, who were presumably more than irritated by the party's lenient approach to Southern white supremacy. Later populist revivals -- Theodore Roosevelt's Progressive Party in the 1910s, or George Wallace's presidential campaigns in 1968 and 1972 -- folded women and industrial workers into their respective definitions of "the people," but also excluded, or continued to exclude, immigrants, African Americans or liberal reformers.

This is why any attempt to associate populism with a particular conservative or progressive tradition -- and thus to condemn it in partisan fashion -- is bound to falter: The logic and rhetoric of populism have been harnessed by diverse groups for different ends. Like elite politics, populism has been a constant throughout America's political history. It constitutes, in the words of the recently deceased political theorist Ernesto Laclau, the "political logic" of the modern nation-state: By outlining and reinforcing the boundaries of who constitutes "the people" and by articulating their sovereignty, populism can serve as the midwife of democracy, the language of demagoguery and as the antidote to elite politics.

Thus, not all populisms are created equal. For Tocqueville, the prospect of populism lay in its link to participatory institutions, and thus in the possibility of cultivating the "habits of the heart" that underpinned popular sovereignty. By contrast, the third-party presidential campaigns of Ross Perot in the 1990s and of Ralph Nader in the 2000s had a distinct populist rhetoric but were ultimately rooted in the logic of reformism, not in a rejection of Washington politics. Likewise, the vision of Bernie Sanders' campaign is not the abandonment of Beltway politics but the reclamation of the political system for the middle class -- which has experienced a steady decline in numbers and prosperity since the 1970s -- and the working class -- which has swelled in numbers and shrunken in social mobility. Sanders' campaign proposals -- universal health care, free education or tightened financial regulation -- are remarkable largely because they have long been excluded from American political discourse even on the left but now attract support among Democrats across age and income brackets. They are populist insofar as they have sparked the imagination and galvanized the Democratic electorate. In most European countries, similar proposals have long registered as common sense.

Democrats are fighting over the political direction of the party, but Republicans are fighting over the direction of the political system.

Yet this particular strand of populism seems profoundly different from the populist debate that is rocking the Republican Party and has largely sidelined establishment candidates. Democrats are fighting over the political direction of the party, but Republicans are fighting over the direction of the political system and the boundaries of political discourse.

Many of Trump's policy proposals are remarkably unimaginative and centrist, but his campaign is unique in the vitriol of its rhetoric and its hostility towards established institutions of American politics. Routine shutdowns of the federal government over budgetary disagreements or calls to ban Muslims from immigrating into the United States have surprised and rocked even the party's conservative elite, and have given a new lease of life to Schumpeter's concerns. The truly revolutionary populism now emanates from the right, and it's not a pretty sight.

Also on WorldPost: