Most people are horrified when President Donald Trump uses “Pocahontas” as a racial slur to attack Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.). But few, if any, are more disturbed by his political punchline than indigenous women.

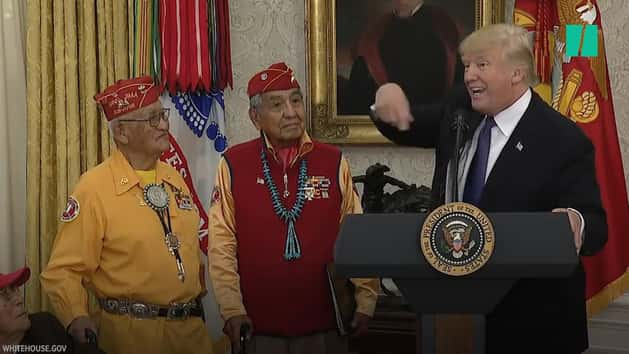

Trump first adopted “Pocahontas” as dig against Warren during his 2016 presidential campaign, when he repeatedly accused the senator of lying about her Native American ancestry. Trump used the phrase again on Monday, during a ceremony meant to honor Navajo Code Talkers.

HuffPost spoke to several native women after the incident. They all said they were deeply bothered by Trump’s comments, which overlook the violence many indigenous women still experience today. Holding up Pocahontas as a caricature of native heritage, they said, ignores the abuse she endured.

“It sends the message that natives are invisible,” said Caroline LaPorte, a descendent of the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians and senior native affairs policy adviser for the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center.

“[Pocahontas] is basically our first well-documented human trafficking victim in the U.S.”

- Caroline LaPorte, National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center

Most non-natives are familiar with Disney’s version of Pocahontas: an American Indian princess who befriends and falls in love with John Smith, a charming lad sent from England to help colonize the New World. Pocahontas saves Smith from being executed by her father, Chief Powhatan ― and they all live happily ever after.

Historians and Native American experts vehemently dispute that narrative. What Pocahontas experienced was “no love story,” LaPorte said.

“She was raped and kidnapped,” LaPorte told HuffPost. “She’s basically our first well-documented human trafficking victim in the U.S. We’ve romanticized her story ― and it’s just not true. Her story is a story of colonization.”

Oral traditions suggest Pocahontas was just 10 or 11 years old when she first met the colonists. She was taken prisoner a few years later and held in present-day Jamestown, Virginia, where she was forced to convert to Christianity.

By the time she was 17, an Englishman named John Rolfe had married her and moved her across the Atlantic Ocean. She spent the next few years as a political pawn, paraded around the English court in an effort to promote partnerships with American natives.

Pocahontas died by the age of 21, effectively ending whatever protection from the colonists her marriage may have provided to her people. The cause of her death is debated. Some accounts suggest she died from pneumonia or smallpox; others say she was poisoned.

Gender-based violence, including sexual assault and intimate partner violence, has continued to plague Native American women at staggering levels.

“Maybe we’re not taken on a ship to England, but somebody is likely perpetuating the same acts of violence against the majority of women in our community,” LaPorte said.

Four out of 5 American Indian or Alaskan Native women experience violence in their lifetime ― more than any other population in the U.S., according to 2016 report from the Department of Justice. The report found that native women experience sexual assault at more than twice the rate at which the average U.S. woman does. Roughly 56 percent said they experienced sexual violence in their lifetime and over 55 percent experienced abuse by an intimate partner.

“Every day we’re dealing with severe violence against native women,” said Amber Crotty, a delegate for the Navajo Nation Council. “I will not allow the president of this country to continue to disregard Pocahontas and what her legacy is. She’s not a character. She’s a native woman who suffered, and her story is our story.”

“We are the most victimized group of people in the United States,” said Terri Henry, the first female tribal leader of the Eastern Band of Cherokee and former co-chair of the National Congress of American Indians’ Task Force on Violence Against Women.

Compounding that trauma is the fact that most perpetrators are never brought to justice. More than 96 percent of sexual violence against native women is committed by non-natives, the Justice Department reports, but tribes are limited in their abilities to prosecute non-tribal members.

“The disproportionate rates of violence are largely due to an unworkable, discriminatory legal system that severely limits the authority of tribal nations to protect our people from violence,” Henry wrote in a statement last year, when she was co-chair of the NCAI’s task force. “As a result, we are denied justice and redress because we are indigenous and assaulted on our homelands.”

Federal funding to address these issues is limited, and some indigenous experts worry budget cuts under the Trump administration would only deepen the funding gaps.

Marilyn Gobert, lead victim advocate for the Blackfeet Domestic Violence Program, said the administration’s proposed budget cuts make Trump’s remarks feel more like a “slap in the face.”

“Our program runs off of federal and state grants,” Gobert told HuffPost, referring to the program that provides support for native women who experience domestic violence in northern Montana. “When [Trump] cuts some of these budgets, that’s taking money from our program to serve the women that are living in violence.”

Funding cuts would hurt a contingency of programs focusing on domestic violence against natives that are already strapped for resources. There are 567 native tribes across the U.S., LaPorte said, but fewer than 60 Native American domestic violence shelters.

These specialized shelters are essential for providing support for native victims who don’t want to leave their reservations and need to navigate complicated legal issues related to tribal courts. Native victim advocates can speak the relevant tribal languages and are able to support victims while being mindful of how the historical trauma of colonization can affect indigenous people.

“If you have to leave your tribal land or state to get the nearest native-run [domestic violence] shelter, you’re being pulled from your culture completely,” LaPorte said. “It’s important for native women to participate in their culture both spiritually and politically.”

“We are not animals. We deserve the opportunity to live our lives free from harm and free from being preyed upon.”

- Terri Henry, former co-chair of NCAI's Task Force on Violence Against Women

In the meantime, tribal advocates are pushing to include crucial amendments in a law that could give native women more protections.

Congress passed the Violence Against Women Act in 1994 to provide additional support to women who are victims of violent crimes. VAWA’s most recent authorization, in 2013, restored tribes’ jurisdiction to prosecute non-natives for specific crimes, such as domestic violence and gang violence. But the law still does not cover sexual violence outside of an intimate partner relationship.

“In native communities a lot of violence against women doesn’t fit that strict definition,” LaPorte said.

Tribal advocates are calling for this year’s reauthorization of the law to include an amendment that would restore tribes’ jurisdiction to prosecute non-natives for other types of crimes, including sexual violence, sex trafficking and stalking.

Until then, these native women want Trump to keep in mind that they are not merely objects of a bygone era, nor relics of the white man’s native fantasy.

“We are human beings,” Henry said. “We are not animals. We deserve the opportunity to live our lives free from harm and free from being preyed upon.”