You live on a world of dry red rock. Something's missing. Air? Check. Gravity? Check. 294 days worth of Tang? Check, check, check. So, what could it be?

A visual sweep of the white half-sphere in which we dwell quickly reveals the deficiency. Of the three color cones a human eye can possess, two barely see use here: green and blue.

The sMars spectrum looks like this: On clear days, a weak circle of blue sky becomes visible through our hazy plastic windows. Small green plants litter the common areas. One little bottle crop even has yellow flowers! The hues of those home-grown leaves is more vibrant by far than the foods we have, particularly the pea-soup shade of our dehydrated spinach. Some of the grow-lights blink and wink in nearly-neon blues and greens. And that, my friends, is the entire palette. Red, white and fleeting hints of blue with a bit of green tossed in here and there.

Suffice it to say, you look forward to - even crave - the smallest traces of color; and moisture, too. The circuits of your central processing units could care less that you've come 50 million miles to conduct critical space research. Children of Earth, be forewarned: wherever you go, your brain continues to expect certain types of input.

So it was that that after 2.5 months of seeing no body of water bigger than a 5-gallon-bucket, and no slice of heaven wider than my spacesuit visor, after reading that the Sun is stripping away 900 lbs of Martian atmosphere per hour, I had the single most vivid dream I've had since landing on sMars - one of the most vivid dreams of my life, in fact. I dreamed about blue.

Mind you, this was not the blurry, pale blue that we see through our Sun-scarred porthole. This blue the kind of deep color we see on our computer monitors, brilliantly alive in the very pictures we take while we're outside our suits. It was the blue that swirls over the mountaintops around Mauna Kea as if the Hawaiian ocean has been tipped into the sky. In my dream, this blue was DAZZLING. It was water - not deep and dark, like seawater, but limpid, like a pond, or perhaps a lagoon. My last thought before waking was, "I'll be right back with my suit."

My eyes opened. The room was dark. I sat up. A crack of light leaked in under the doorway. 7:20, said the face of my solar-powered watch (which I hang in the porthole windows once a week to charge up). That's the time the metronome in my head likes to wake me up if I'm not already awake. Dear metronome: could you wait until after I've had a quick dip next time?

I hopped out of my bunk, washed my hands in recycled water, and headed for the kitchen. When I arrived, the usual systems sign, "Water Condition: Normal" had been replaced with, "Water condition: Restricted." A quick glance thru the porthole told me that it was going to be a low power day, too. Welcome to a very space-like day on simulated Mars.

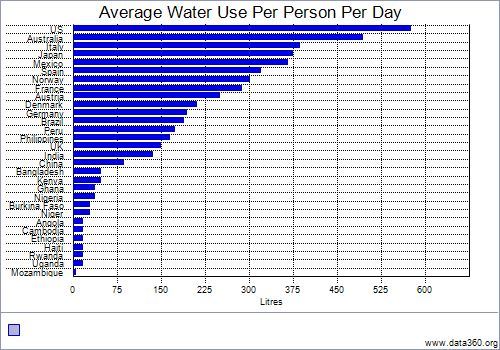

Not that we waste water even on an average day. When Water Condition = Normal, individual HI-SEAS crew members use less water than the average person living in Nigeria. That's ~5 gallons, or 19 liters, per person per day for eating, drinking, preparing food; washing dishes and clothes; cleaning the habitat and our bodies; and watering plants. That's low. So low, in fact, that it's only a few more liters per day than the amount available to people living in water-starved regions like Uganda, Rwanda, Haiti, and Ethiopia.

Water Usage on the Planet Earth. Data courtesy of 360 Data.

We can get away with this in large part because of our composting toilet system. The toilets here use exactly zero water. On top of that, we recycle the water in our sinks and shower in buckets, later transferring the excess water to tasks like washing floors.

Owing in large part to flushing toilets - plus watering lawns and long showers - the average America uses 525 liters of water per person per day. To put that into perspective, the average Olympic sized swimming pool holds 2,500,000 liters.* So, the average American uses up an Olympic Swimming pool full of water every 13 years or so. By contrast, The average sMartian (assuming we are average) would take 360 years to burn through the same amount.** And the average astronaut..?

Right off the bat, unlike their North American counterparts, astronauts living on the ISS don't use 50 liters of water to take a shower. For them, it's far closer to 4. Unlike sMars, in terms of water, the ISS is a completely closed system. Almost every drop is captured and reused. This includes water from obvious places, like peeing, tooth brushing, and hand-washing, as well as less-obvious ones, like breathing. Fun fact: we each lose about 800 ml a day of water from our bodies just by breathing through our mouths and our skin (aka sweating). Recycling all of this fluid amounts to 40,000 pounds of water that DOESN'T have to get shipped to the ISS from the Earth every year. At $10,000/pound, that's a pretty spiffy cost-savings.

Now the question is: how much water will we have to send to Mars, and what will it cost?

The people here on Mauna Loa are getting by on not that much water a day, but 19 liters/person for a six-person crew on a 1-year mission still equals a LOT Of water (41,639 liters, or 1.7% if that Olympic pool***). Let's say that we only send along enough for Mars explorers to live under WATER CONDITION = LOW. That's 5 gallons total, 19 liters exactly, used by the entire group every 24 hours. Think about 1-liter soda bottles. Empty 19 of those into a tub. That's all the water the six of us use on a CONDITION LOW day. When on restriction the whole HI-SEAS crew uses less water than the denizens of the vast deserts of Mozambique. Still, sending only that much water would cost...wait for it...more than $152,000,000 USD. Which...is a lot of money.

It's critical to note that on those low water days, we don't shower, fill crop tanks, clean the hab, or do laundry. Being able to do those things on a regular basis is important. That's why, according to the UN, the "poverty threshold" for water is 50 liters per person per day. Around here, we use 10x less than that every day. To send a crew of six people to Mars with a water supply that would keep them well below the water poverty level would cost around 913 M.

So, what's the alternative to spending that much cash to send that little water? There are two that I know of.

The first option is to make water using a water reclamation and purification system like the one on the ISS. Good news: this system works like a charm AND only costs $250 million dollars. That number would have sounded quite large a minute ago. Now that you know what it would cost just to launch 5 gallons per person per day into orbit, a reclamation system seems like a bargain-and-a-half. There's even more good news: using pretty standard fuel cells, you can create water at the same time that you are making energy. Now you're cooking with gas, quite literally. Hydrogen goes into the cells on one end. Out comes water, oxygen, energy, and heat: all things you really need in space, and on Mars as well.

Hydrogen Fuel cells at work. Image Courtesy of the US Department of Energy.

The second option is to find water, or at least find some of it, when we get there. That possiblity is closely tied to a question that we've been asked continually since October: what about water on Mars?

Yes, absolutely: it's there. It flows. As beautifully described by our Chief Engineer, we've had photos of "water-like" changes to the landscape since 2011, which is when Andrzej pressed the button and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter took the now-classic photos of the Horowitz Crater. The force beneath those flows is now known to be water - freezing, melting, and refreezing again.

What does that mean for us, as future explorers? Well, it's not bad news, that's for sure. The more specific question is: what are the odds that we're going to be allowed to use that water for essential tasks like cooking, cleaning, drinking, and growing plants?

My guess is: if we are allowed to at all, it will be later, not sooner. For at least the first 5 or 6 years, we'll be furiously searching for signs of life in the area in and around those flows. We won't be digging wells for a good long while. Distilling water vapor from the threadbare Martian atmosphere is a possibility. The efficiency of that process is unknown, but we might be able to take advantage of a fun fact: at night, the small about of atmosphere that Mars does have becomes 100% saturated, meaning that any water hanging around may well condense out and become collectible.

In the end, there are surprisingly few things that we need to survive for a year in space. The list includes air pressure, and the right mix of gases to breathe; nutrition; radiation shielding; water and energy. Current technology has the tools to handle all of this: the water reclaimers, the fuel cells, the air purification and compression systems. We bring the tool and make the magic happen.

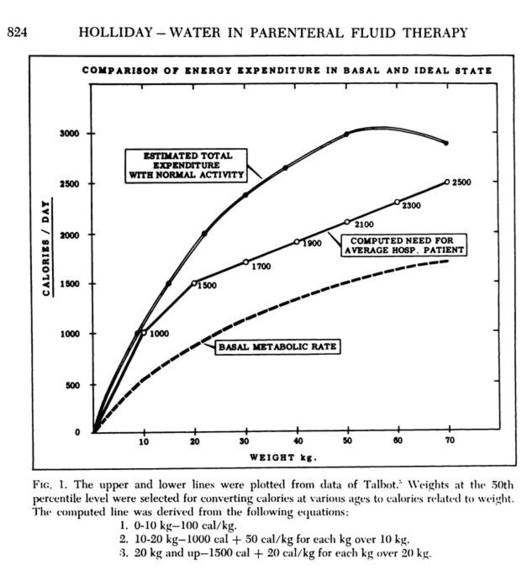

As a doctor, I would be much happier if that year included gravity, of course. For now, I'll be content with my dreams, and the occasional bright flashes of blue they bring to my otherwise rather red and white world. I'll also ponder this: we know how much adults on Earth have to drink to stay healthy, and we know how much adults in zero gravity have to drink to stay healthy. We have no idea how much people on Mars will need to drink to maintain their fluid balance, and to live and work in good health. That depends upon what 1/3rd gravity does to the human metabolic rate - after half a year in space (or more). That, my friends, will be a mystery, right up to the point when we put the weight of our feet down on that dry(ish) red earth.

Human water requirements vary by age, state of health, and level of activity. Image courtesy of University of Texas Medical Branch.

---

The Various Mathy Bits (aka The Appendix):

* Assuming pool's volume to be 25m x 50m x 2m = 2,500m3; 1m3 of water is 1000 Liters. So, 2,500 x 1000 = 2,500,000).

** 6940 liters per year is our current individual usage on an average day at HI-SEAS, as opposed to 191756 for the average American (We use 96% less water).

*** (19 * 6 * 365.25) = 41639 liters for the 6-person crew

**** 5 gallons at 8.34 pounds per gallon (that's deionized water at ~ 65 degF) = 57838lbs x 365.25 x $10,000/lb