I recently read an LA Times article about a public feud between artist Damien Hirst and British art critic Julian Spalding, the latter of whom had written a short book, Con Art -- Why You Should Sell Your Damien Hirsts While You Can. I thought it might make an interesting blog topic, so I downloaded and began reading Spalding's book, a no-holds-barred polemic on contemporary/conceptual art.

When about half way through I read this:

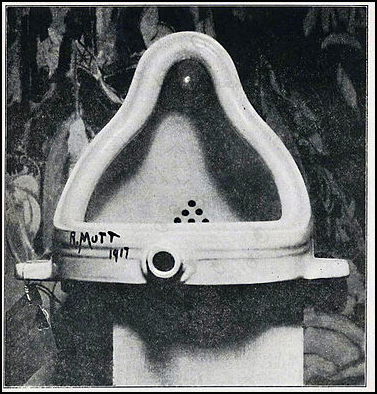

"[Duchamp's] apotheosis was consummated in 1999 when the Tate Gallery bought his urinal, called Fountain, for $500,000, to celebrate the century of art they thought he'd done so much to create. Unfortunately for the Tate, the urinal wasn't his. The latest research [...] has now proved beyond any shadow of reasonable doubt -- that the urinal wasn't submitted to the Society of Independents exhibition in New York by Duchamp but by the redoubtable Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven."

Wait... what? Forget the Hirst/Spalding spat! Who the heck was Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven? If what Spalding claimed was true, why wasn't that the headline? I needed to dig deeper.

Fountain by R. Mutt; Photo: Alfred Stieglitz

Spalding cites two sources to back up his claim, Irene Gammel and Dr. Glyn Thompson. I immediately ordered a copy of Gammel's 2002 cultural biography Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity and began to read about this amazing, overlooked artist and poet who was light years ahead of her time.

Born Elsa Plötz in 1874, the future Baroness arrived in Berlin in 1893 ready to experience life in the extreme. Gammel writes:

" In a dazzling odyssey of sexual roles and experimentations she now began to armor her personality, emerging as a tough sexual and artistic warrior in her conquest of the modern city. Her ambivalence as androgyne allowed her to test a stunning range of erotically charged positions -- young ingenue, female flâneur, erotic art worker, priapic traveler, chorus girl cum prostitute, actress, cross-dresser, lesbian, and syphilitic patient -- all in a span of just a few years."

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

The flamboyant Elsa eventually follows her second husband to America after faking his suicide to escape creditors. When he leaves her in 1913, she makes her way to New York City, the same year as the Armory Show in which Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase becomes a succès de scandale.

Now 40 years old, Elsa Plötz Endell Greve marries Leopold Karl Friedrich Baron von Freytag-Loringhoven (a short-lived union) and the Baroness is born. On the way to the wedding, Elsa finds an iron ring on the street and calls it Enduring Element, her first piece of found-object art. This is a full two years before Duchamp and Picabia arrive in New York and Duchamp coins the term "ready-mades."

Elsa plunged headfirst into New York's avant-garde artistic circles. When she met Duchamp, 13 years her junior, she immediately fell in love and began her pursuit of him. Duchamp resisted her advances, causing her to refer to him as her "platonic lover." The two lived in the same apartment building for a time and were well acquainted.

The key piece of evidence in Gammel's compelling case for why the urinal may have been Elsa's is a letter Duchamp wrote to his sister in April 1917 in which he states:

"One of my female friends who had adopted the pseudonym Richard Mutt sent a porcelain urinal as a sculpture; since there was nothing indecent about it, there was no reason to reject it." (When he speaks of not rejecting the urinal, Duchamp is referring to the fact that he was a board member of the Society of Independent Artists who chose work for the exhibition.)

Is this the smoking gun? Gammel stops short of saying so, careful to point out that final, conclusive evidence is missing, but "there is a great deal of circumstantial evidence that points to her [Elsa's] artistic fingerprint."

As for Spalding's other source, Dr. Glyn Thompson, I wasn't able to find anything published except an online PDF of a 2008 doctoral thesis for the History of Art and Cultural Studies at the University of Leeds School of Fine Art, titled Unwinding Duchamp: Mots et Paroles à Tous les Étages.

It is well beyond the limits of my time to read Thompson's entire thesis, so I tried keyword searches ("urinal," "fountain," "baroness," "elsa," "freytag-loringhoven") to see if I could find the corroborating evidence Spalding cites. I couldn't.

Given the urinal's enormous influence on twentieth-century art, I would very much like to know Spalding's further substantiation that "has now proved beyond any shadow of reasonable doubt" that the Baroness, and not Duchamp, was responsible for the iconic urinal. If you know of this evidence, you can email me at jane@offrampgallery.com and I'll report it in a future column.

Is Spalding right when he claims "Duchamp stole the idea from, of all people, a woman to cement his reputation. He then commissioned a set of replicas to sell -- cast of a copy of a found object! They sit like thrones in the major collections of modern art around the world." If Spalding is right, how does this alter your view of Duchamp and his legacy?

Cross posted from Jane Chafin's Offramp Gallery Blog.