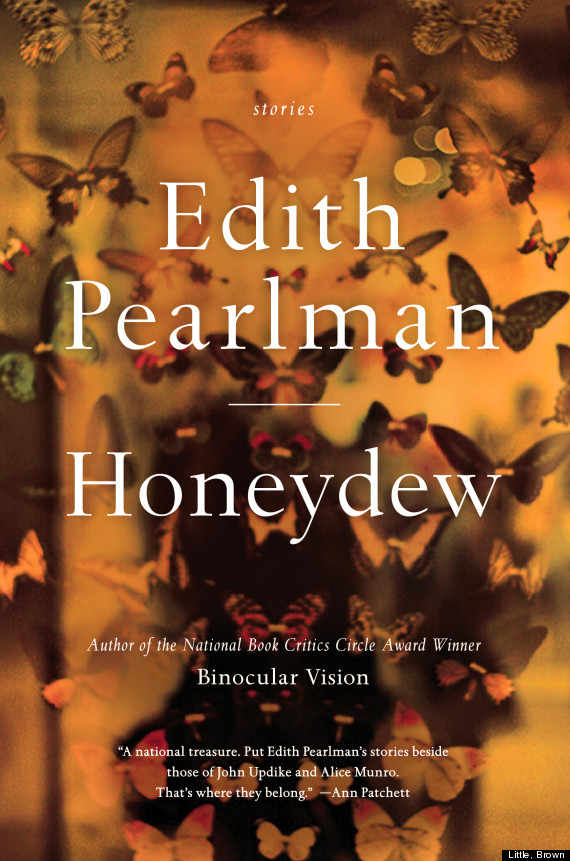

Rejected Covers is an ongoing series for which artists reveal their inspirations and unused design ideas for popular titles. Below, Little, Brown Senior Designer Lauren Harms shares the process of selecting a spare yet melancholic image that suits the touching quality of Edith Pearlman's acclaimed short stories, for her latest collection Honeydew.

Edith Pearlman’s story collections are intimate and honest portrayals of life. Edith’s editor, Ben George, said to think elegant and sophisticated, with a touch of the melancholy that Binocular Vision, Pearlman’s previous collection, had portrayed so well. A cover that would be quiet but striking, like honey infused with sunlight.

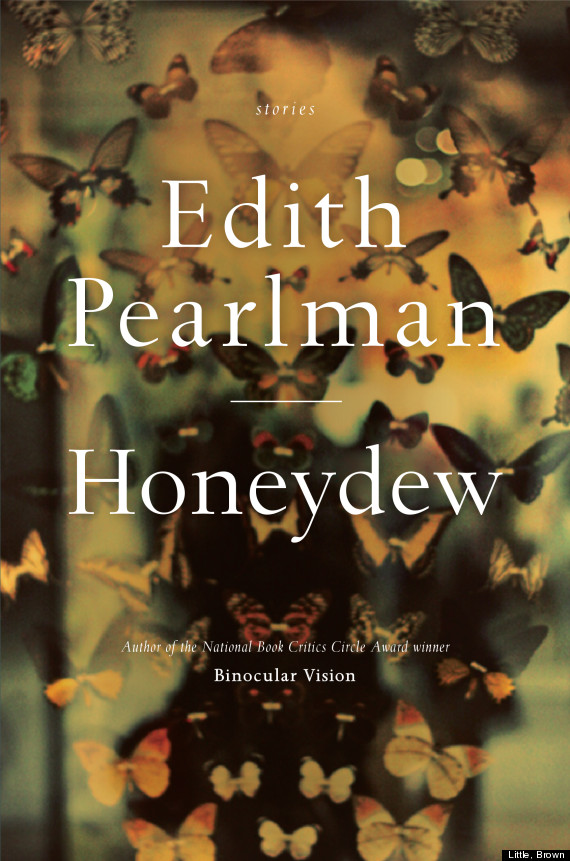

After reading a few of the stories early on, I started to think about the beautiful, ephemeral things in life: iridescence, bioluminescence, prisms, sunbeams. There’s a character who sees pentachromatically, which means they interpret five color channels instead of the three the rest of us see. Because of that, I wondered if there was a way to portray a part of something as more vivid. Also, the title story involves a drug that is made from a ground-up moth grub found in Brazil. That spurred the idea of a macro shot of moth or butterfly wings.

Shortly after getting the assignment to work on Honeydew, I was browsing Pinterest. As a visual person, I love Pinterest. It’s a great tool for collecting inspiration and every once in a while I’ll come across an illustrator or image that relates to something I’m working on. One day, I was scrolling the infinite scroll and came across a beautiful image of butterflies, soft and slightly out of focus, with flickers of light. I knew this would be a great image for Honeydew.

The clothing brand Anthropologie had pinned the photo, which led to a Tumblr post, which led to the Flickr profile of Sophie Banh (PSA: credit the images you repost and share that aren’t yours!). Sophie is a design student in Australia and has posted on Flickr some really wonderful photographs she’s taken. After a quick search I was able to find her design and illustration portfolio site and contact info. She graciously allowed Little, Brown to license use of the image.

As you can see, the original image has a different coloring. I warmed it up with some color adjustments, making sure to keep the depth. We also decided to print on a pearlized paper that radiates and invites you to pick up the book.

Many people have asked why I chose to make the title and author name the same size. To me, it was instinctive from the start. They hold equal resonance, this is Edith Pearlman’s Honeydew.

Related

Before You Go