The films of Wael Shawky's Cabaret Crusades are on view at MoMA PS1 through August 31, along with installations of selected sketches, sets and marionettes that the artist used throughout filming. For directions, schedules and other information, consult the MoMA PS1 website. For the viewer going into the films with little or no knowledge of the medieval Crusades and Jihads, see these Four Brief Yet Crucial Turning Points of the Crusades and Jihads for Better Understanding the Cabaret Crusades films.

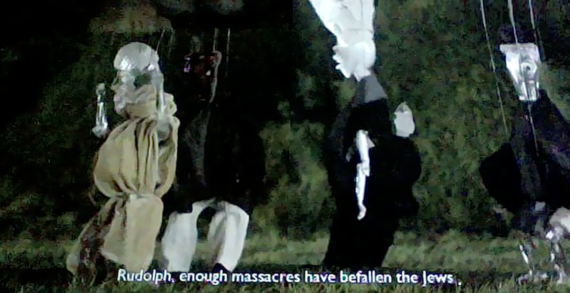

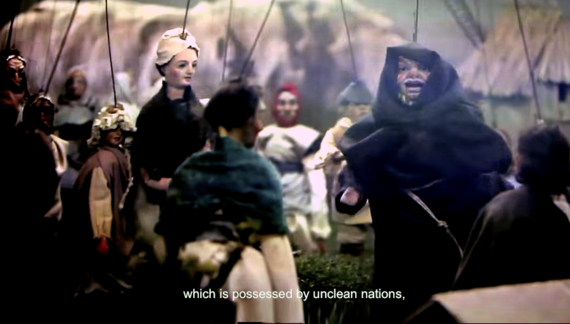

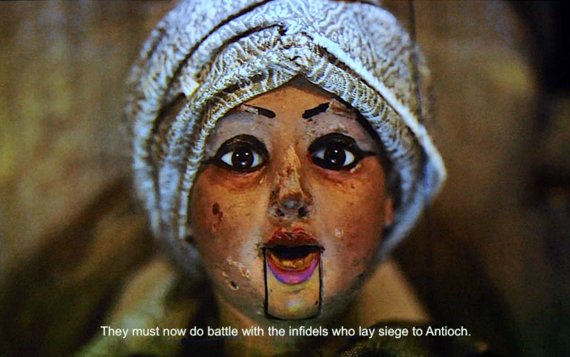

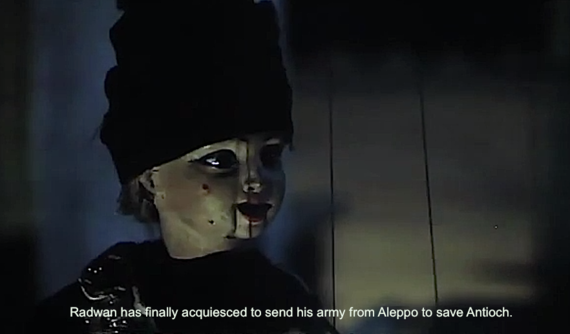

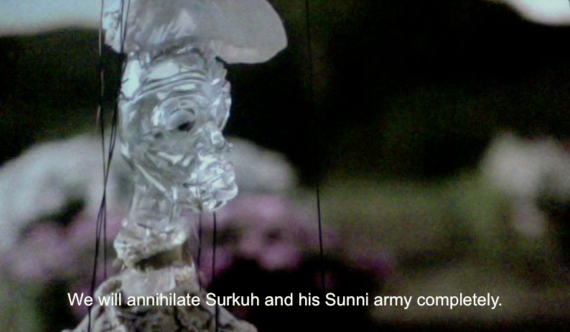

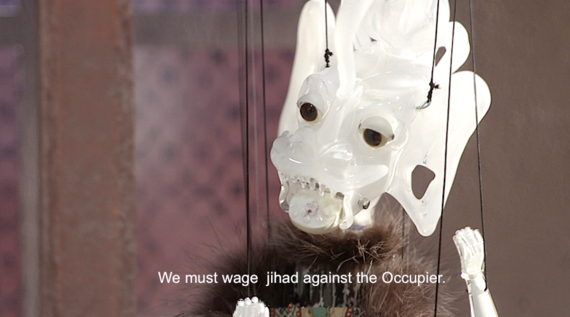

A revelatory scene establishes the lacerating historicism of The Secrets of Karbala, the third film in Wael Shawky's trilogy, Cabaret Crusades. That's historicism, not history, the deliberate seeing in the past the makings of the present. Although the preceding films have already traced the long shadow cast by the religious Crusades and Jihads of the 11th-to-13th Centuries onto the geopolitical conflicts of the Middle East today, Shawky returns to a moment before the battles have begun. We find ourselves amid a verdant wilderness upon which two surreal groups of marionettes made of Murano glass converge somewhere between Cologne and Constantinople. Marionette action is never smooth or subtle, and watching the figures onscreen popping up and down in medieval garb is comical in terms of their limited physical repertoire of raised hands and twisting heads. Shawky's remedy for conveying ferocity is to favor a montage of close camera angles and voiceovers in classical Arabic as his means to animate what is often the puppet's general inaction.

Our amusement dissipates as a title onscreen informs us we've arrived just as a spontaneous pogrom is about to be inflicted on Jews. But as the violence is about to erupt, a marionette dressed as a monk rushes forward to stop the Christians' leader, 'Rudolf', from attacking the Jews, and at least this time it seems there is no violence.

The scene, though childlike, has no less than set our expectation for one half the trilogy's antagonistic subject -- the fanatical Christians who set out in 1095 CE (487 AH by the Muslim calendar) to battle the equally fanatical Muslims who for three centuries have been taking possession of the Christian shrines of Byzantium, Palestine and Syria. This particular group are followers of the historical People's Crusade led by Peter the Hermit en route to their Holy Land, in what is the true first crusade from Europe to Western Asia, preceding the more famous Papal First Crusade by a year. Without a royal or ecclesiastical chaperon, the People's Crusade accumulated upwards of 20,000 poor illiterate and criminally-inclined belligerents who repeatedly erupted into genocidal melees in the name of their faith and killing thousands of Jews and other 'heathen' on the way to Jerusalem -- the place they looked forward to confessing their sins.

Shawky needn't say any more about the Jews in his trilogy. And not only because they aren't the leading protagonists in the conflicts. He need only show us one two-minute display of antisemitism for us to recognize he has sufficiently tipped the balance of human atrocities in the Christians' disfavor by counting on us to recollect the indiscriminate annihilations of Jews that would come throughout the next nine centuries, just as they had likely raged the previous nine. In fact, the episode is also indicative of the centuries-long crusades waged in Europe to convert or kill nature worshippers in the isolated regions of the Balkans, Scandinavia, the Alps, the British Isles, and nearly all of Russia. Even Southern France was a religious war zone where millions died in defiance of The Papacy and The Cross. But extinct societies can't represent their pasts or remind us that we are alive today most likely because our ancestors annihilated people like them for being less brutal, less organized and less equipped. Their extinctions also remind us of our own potential obsolescence. Picture ISIS attaining nuclear weapons.

As compelling as living lineages are, it is as relevant to us today to understand how the myths and histories inform us in our lives today, and there is no better vehicle for this than our arts and entertainments. In narrating long expositions on the Crusaders and Jihadis of the 11th-to-13th centuries, Shawky alerts us to the contemporary ideologies and events informing militants who mythologize modern versions of crusaders and jihadis today.

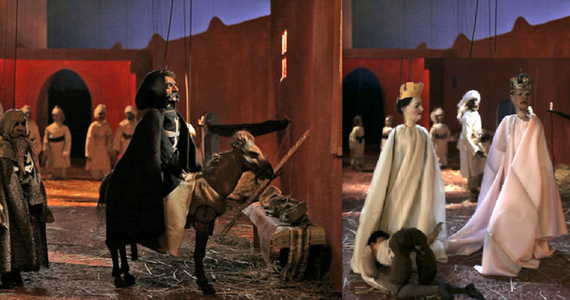

We can readily see among the Crusaders a glaring contrast between the commoners on foot and the knights and royalty on horseback. What may require explanation is the social evolution of the Christian class structure that is at root to the crusade here being waged, given that some six centuries earlier Christians were nonviolent exponents of "the new covenant of love". New Testament scholar John Dominic Crossan explains that the radical arming of Christians came during the 4th Christian century, when a newly imperial figurehead in the form of the Holy Roman Emperor not only came to defend and expand Christendom, but also ideologically and militaristically transformed the Church from a desert sanctuary for the martyred to a militaristic Holy Roman Empire through which religious and ethnic cleansing became pardonable when waged in the name of the Faith. Shawky should seriously consider chronicling the Church's 4th-to-5th century militarization as a backstory if he produces a fourth Cabaret Crusades film, especially as the 'Karbala' for which his film is named, provides the backstory for the Jihads of Islam.

It is this Imperial class of Crusaders that the British historian and Christian Crusades scholar, Geoffrey Hindly, reminds us tantalized such modern heads of state as Kaiser Wilhelm II and Chancellor Adolf Hitler to represent themselves to their supporters as the heirs to the Holy Roman Emperors waging crusades against the heathen and heretic Slavs -- or as modern Chalemagnes vanquishing the Saracens from European shores. During World War I, we are told that with his unit capturing Jerusalem, British General Edmund Allenby compared himself with Richard the Lionheart, while others compared Allenby more correctly with French Duke Godfrey of Bouillion, the Christian "liberator" of Jerusalem in 1099. During the French takeover of Syria in 1920, French General Henri Gouraud visited the tomb of Saladin, the greatest of the Muslim vanquishers of Crusaders, to crow, "Awake, Saladin. We have returned. My presence here consecrates victory of the Cross over the Crescent."

Both Muslim and secular heads of state in the Middle East have been no less narcissistic in their identifications with the Jihadis who ousted the Crusaders. King Faisal bin Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi, the rebel king of Syria and Iraq (and friend to T. E. Lawrence) in the 1910s and 1920s, and after him Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein in the 1950s, and more recently Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, terror patriarch Osama bin Laden and now the self-proclaimed Caliph of The Islamic State of Iraq, Syria and the Levant, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, all strove to expel the Western occupiers in the Middle East by envisioning themselves as the new Saladins in a renewed quest to vanquish modern Western Crusaders. And yet it is such identifications with historical figures that often proves obscenely deceptive, as in the case of Saddam the mass persecutor of Kurds identifying with Saladin the great leader of Kurds.

Saladin, the most noble and generous of the Muslim protagonists is well represented. But Shawky spends as much screen time implicating the betrayals and massacres perpetrated on weaker and unarmed Muslim populations by less formidable Jihadi antagonists who used the threat of impending Crusader assaults as pretexts for taking possession of attractive principalities and deposing their dynasties.

We like to think of art being the most reflective sensor of contemporary cultural dynamics, but rarely are we treated to such a profoundly artistic analogy of our own geopolitics with the geopolitics of such a remote and infamous past as those pictured in the films made in the last five years by Shawky. There are, of course, on a larger scale and with human actors, the renowned precedents of Sergei Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky recalling the Nazi menace threatening Russia in 1939. There is also Eisenstein's Ivan the Terrible satirizing Stalin's genocidal mania right under the dictator's nose, and Andrei Tarkovsky's Andrei Rublev paralleling his contemporary Soviet society with its persecution of nature worshippers by the Russian Orthodox Church, a thinly veneered indictment of the Soviet persecution of all lifestyles outside the Marxist-Leninist purview.

Shawky may not have the means or production skills of such masters, but we shouldn't underestimate his modest sets, deceptively-unassuming humor and the beguilingly-cute horde of marionettes packed into his films as mere parodies, especially given that in the totality of Cabaret Crusades there is barely a face or a figure that appears onscreen without personifying some manner of intolerant, often mercenary sociopath. The sting of Shawky's three films, of course, is the after-realization that the sheer number of sociopaths in succession in his films imply that each of us contains the germs of intolerance and the will to authoritarian power that can turn our loftiest ideologies into coercive, hypocritical and autocratic dogma.

While the Crusades and Jihads have in recent years been transformed from historical anachronisms into inspiration for terror, more and more Christians and Muslims buy into the intransigence of their own faith, thereby fortifying the reprisal of decrepit myths of salvation and reward in heaven among millions of the naive faithful. If the predominant myth of Islam fantasizes jihad setting things right after two centuries of Western colonization, for the Evangelical Christian the modern Crusader myth perpetuates the election of politicians who ensure that America's military prowess and billions of dollars will continue to be set aside not so much for the protection of Israelis, but to ensure that American Christians will always have access to the Christian shrines and historic environs of the Holy Land -- despite that before the Israeli state existed, Muslims protected these very sites and their access to Christians for a full millennium.

But history can be inconvenient for a Western media eager to saddle Muslims with the myth of harboring lust for the reclamation of the Muslim empire that was lost with their failure in the modern age to keep apace both militaristically and economically with global nations. The larger reality is that like everyone else, Muslims desire modern economies, modes of production and convenient consumerism like everyone else. We see glimpses of the masses in Cabaret Crusades, but for the most part they are faceless victims, not protagonists in the drama. Part of this is the fault of the original medieval chroniclers as much as of modern historians. Ordinary people just didn't get chronicled.

As to why Western audiences for art are only just now embracing art about Muslim culture and history has more to do with our culture's gradual shift away from the Modernist closure on faith-based paradigms than any religious or state opposition. At the root of Modernism, the 18th-century philosophes of the Enlightenment didn't have respect for religion in mind when they sought the freedom to publish anti-religious literature. In keeping with the philosophes' prejudice favoring nature, secular society, and deism, the development of a secular Modernism parallel to religious faith and other spiritualist offshoots hardened further with the 19th- and 20th century positivist philosophies seeking to keep philosophy apace with science by asserting a truth that can only be ascertained by 'objectively verifiable facts' (Comte) and by a logic 'which is not at any point obviously wrong' (Wittgenstein/Russell). Modernist art, literature and cinema for nearly three centuries, with few exceptions excluded religious art, except in the rare occasions that a significant Modernist production -- and then primarily during Modernism's Existentialist phase that included theological contingencies -- contemplated or depicted an individual or population facing a severe crisis of faith unique to Modernism.

It wasn't until the 1990s, well after the offerings of Modernism had been exhausted, that cultural contributions from outside the West began to be assimilated into the canon of significant contemporary art. And yet, for two decades the only artist to significantly portray Islamic cultural values and lifestyles and be welcomed by the Western artworld was Shirin Neshat. Such tokenism survives today with regard to Islam despite there being a remarkable influx of compelling artists from Muslim cultures working in Europe and the US with themes and motifs that reference Islam culturally if not religiously. And this is within the most liberal enclaves.

This year, however, MoMA's Klaus Biesenbach, always a courageous if scandal-prone curator, pried open the closure on art that is topically faith-based when he brought Cabaret Crusades, to MoMA PS1. Although the films decline to make religious claims for Islam or any other faith apart from those central to the unfolding historical drama, substantial representation of the primary rituals and expectations of Islam -- the Hajj to Mecca, the observance of the feast of Ashoura, the militant imperative of choosing between conversion or death -- inform central and deciding scenes however impartial, yet passionate in presentation. Shawky also introduces Western art audiences to Islam's most controversial political and sacred controversies, including its sectarian and anti-Western polemics. And as if the Western artworld were a single entity that knows it must make up for its past eurocentric neglects, Shawky has in recent years been seen and celebrated in prominent galleries in Europe, in addition to those of North Africa and the Middle East. Yet the slow trickle of Western recognition that until recently has been accorded Shawky and other artists acknowledging their personal and artistic formation within Muslim cultures make it apparent that they have still to prove that they aren't Muslim extremists. Of course, while no one in the liberal enclaves of art wants to admit to a censorship of Muslim sensibilities in art, most will concede that it has taken the demise of Modernism's more severely positivist principles to pry open the contemporary art world in the West to non-Western art that isn't formalist or politically conservative. Tragically, it seems it may have also taken the events of 9/11 and the American occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan to impel a dissenting crosscultural effort among critics, curators, gallerists and especially collectors.

In fact Shawky's Cabaret Crusades is a virtual compendium of medieval extremism, terrorism, assassination and warfare endemic to both the Christian and Muslim societies. But the treatment of two traditionally oppositional faiths compounded with the singular fact that Western audiences are openly engaging with such religious paradigms, however historical, implies that Biesenbach has successfully implemented a new phase of historicism at MoMA and PS1. While we are not near to assuming a zeitgeist historicism that replaces the present predilection for progressive, if not avant-garde, innovation, we are seeing such New York art institutions as The Met, MoMA, The Guggenheim, The Whitney and The New Museum implementing programs and exhibitions to expand crosscultural debate and artistic conflations even when threatening what sacrosanct Modernist traditions we cling to. In this regard Shawky, with Biesenbach's help, is realizing the capacity of the secular space to function as a meeting place for all potentially amenable ideological opponents capable of integrating the diversity of faith and ideology bound by the democratic social contract. Nothing can be more extinguishing to anti-democratic extremism than this.

Despite being bereft of human actors and breathtaking location shots, the historicism of Cabaret Crusades includes moments as existentially shattering as the cinema of Pasolini, Bergman, Godard and Amtonioni, all of whom explored historicism as a vehicle to comment on the inhumanity of the present. Strangely, when these visionaries were at their peak production, Susan Sontag in the late 1960s assumed the radical Modernist role of dissenting on the basis that she saw historicism in art dangerously displacing the more urgent enterprise of "system-building", that is accounting not for "what is", but futuristically assuring what "ought to be". Even as recent as twenty years ago, when the Modernist avant-garde in the West was thought to have nothing more to offer the future of art, the appearance of something like Cabaret Crusades seemed untenable, especially in that it doesn't issue from Europe or America. While the postmodernists of twenty years ago might have appreciated the film's independent efforts and Shawky's skill at elliptical storytelling, all but the most progressive audiences would have likely found Shawky's sustained and deeply immersive exposition on the horrors of medieval Islam jarringly anachronistic, even reactionary to Modernism.

Sontag's complaint about historicism is no longer valid, given that global society is system-building its way to dangerously exhausting the earth's resources, wildlife and devastating the world's indigenous traditions. Whereas Sontag's was still a forward-leaning society that could believe in an avant-garde, today it is our collective immersion in history through which we unearth deeper motives and lessons that seem surprisingly relevant to our own situations. Each generation has to relearn that system-building is best implemented with an attendant historicist eye, if not a guideline intent on history-making. That the medieval Crusades and Jihads still have something to teach us about the present situations in the Middle East becomes glaringly obvious when everyday the media reminds us that a new generation of jihadis named ISIS revere their own Sunni Muslim history of domination while reviling all other histories they project to be opposed to theirs. With this realization we must distinguish between the historicism that Shawky engages for our enlightenment from the historicism that ISIS wages for its ideological entrenchments.

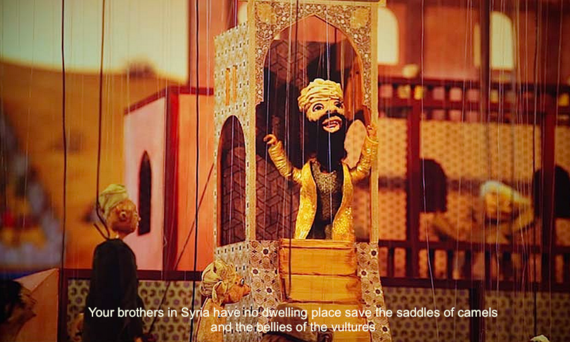

We can begin distinguishing Shawky's enlightened historicism by considering how it is operative in the choice of his pre-production materials. For not only is his subject historical, but also his reprisal of the simple and ancient media of wood (the 200-year-old marionettes Shawky borrowed from the Lupi collection in Turin), clay (painted ceramic puppets designed by Shawky) and Murano glass (designed after African sculptures in the Metropolitan Museum of Art) that the artist employs to bring his actor-marionettes to life. Such an immersion in period materials and craftsmanship of his subject period is more than a challenge posed to the modern technocratic and aesthetic sensibilities of the day. It is the visual artist's version of the method actor's drill for nurturing an immersive empathy with his subject by inhabiting his character even when she is off the set or stage. Of course, the films are recorded and disseminated in HD video, a requirement that mitigates our alienation from Shawky's historical media with the comfort of hypnotic screens.

Shawky's overlapping of modern and premodern media runs parallel to his overlapping of modern and premodern societal and political orders. Before indulging the latter, we might first consider as exemplary the paradigm for the overlapping of temporal global productions offered by the late sociologist Daniel Bell, who held that modern production is always only in part modern. In national and international industry alike, today's postindustrial productions (digital media, communications and electronic industries) always coexist with and overlap both preindustrial production (agricultural and cottage industries) and industrial production (mining, construction, assembly line manufacturing).

It is perhaps unsurprising that an artist from Alexandria, Egypt, even in an age of 3D avatars, might reach back to the roots of national identity and cultural heritage to a time when the tombs of the Egyptian nobility were supplied with what are the oldest marionettes known. More relevant still is the enthusiasm that marionette theater elicited equally among the medieval Muslim and Christian populations. For this reason, Shawky doesn't just borrow the medieval theatrical medium, he evokes the medieval religious institutions on both the Christian and Muslim sides of the conflict, as historians tell us medieval churches and monasteries of Europe used marionettes to stage scenes from the Gospels and the Chanson de Roland, a dramatization of the legends of Emperor Charlemagne and his Christian knights vanquishing the invading 'Saracens' from Europe.

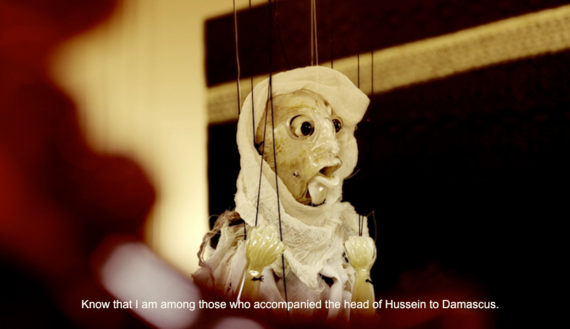

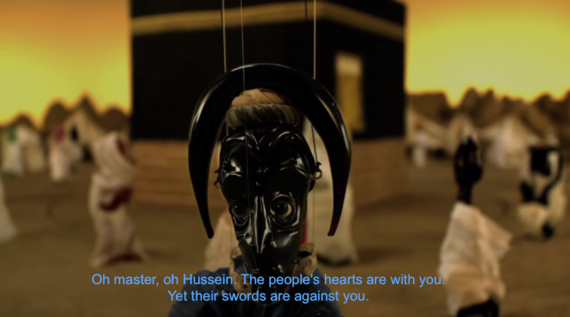

Similarly, medieval Muslims utilized marionettes to perform reenactments of the founding and rise of Islam, and quite possibly even the passion plays reenacting the martyrdom (shaheed) of Hasan ibn Ali and Hussein ibn Ali, the assassinated grandsons of the prophet Mohammad observed on the Muslim feast of Ashoura. Shawky even opens his third film, The Secrets of Karbala with a prolonged and defining reference to -- and later a depiction of -- the battle and assassination of Hussein, his infant son and male relatives at Karbala. If Shawky's selections are at all predisposed to piety, it doesn't show in the work, and the bold choices of selecting what conflicts are depicted and how they are filmed dissipate concerns of reverence ever supplanting the hard scrutiny required of art.

The use of marionettes does have the psychological effect of enticing us to feel as children. This is particularly true when, in Shawky's first film, The Horror Show File, 2010, the antagonists are seen with the faces of children. Or in the second film, The Path to Cairo, 2013, when they have the faces and bodies of animals, or the third, The Secrets of Karbala, when they resemble appealing monsters. It is a strategy that in disarming us sets us up with expectations of innocent amusement and adventures without ever being reduced to parodies. In this fashion, Shawky undercuts our expectations with the narration of heinous betrayals and bloody atrocities committed on all sides. In being so lulled into a child-like regression, we unconsciously become one with those believers of faiths we watch setting out to liberate the enclaves of Truth from the barbarism of infidels, only to find that they/we have become if not the monstrous perpetrators of horrific crimes against humanity in the process, certainly we are among those complicit with their actions. In this sense the message Shawky imparts is that the best way for a first viewing of his work is to be as children are in our open reception and proclivity for learning the relative truth at hand.

On the other hand, the exclusively Muslim music that Shawky has selected discloses that we are in fact positioned to see the conflicts through Muslim eyes, and the films are particularly effective in achieving this aim. At least this viewer found his receptivity to the narration of Muslim events more palatable with music, especially when the lyrics are alienating for their ideological rigor. No doubt for Shawky, assimilating such an overtly Islamic medium as music for the human voice is meant to heighten our capacity for a universalist mysticism, especially given that a profound and passionate embrace of mystery animates Muslim poetry and the infectious melodies and rhythms that strive to effect transcendence throughout the films -- though for non Arab speakers, the subtitles may intrude on that experience -- which comes more naturally to anyone knowledgeable of the classical Arabic spoken and sung throughout the films.

With only two exceptions within the three films combined in which women sing, male voices intone in a unison reminiscent of group prayer or the recitation of ritual litanies. Many of the songs are mournful and confessional, with the effect that they melodically and rhythmically impel us through a succession of historical and psychologically-revelatory anecdotes, with the most compelling being songs reminiscent, if only remotely, of sacred places of the heart and body. In a sense, not knowing the classical Arabic enables us to project a Modernist-like appreciation of the formal beauty of the music and songs even when the subtitled translations are precise. But such a retreat to Modernist sensibilities defeats the purpose of interacting with Shawky's art, as well as keeps us closed off to its deeper, universal meanings -- if such a thing exists.

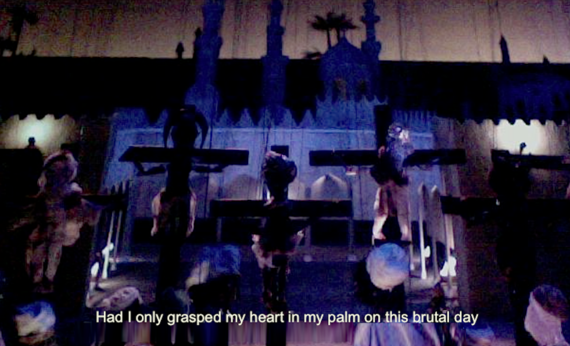

For instance, Shawky in 2013 conveyed to Art in America's Faye Hirsch that he employs the traditional music of fidjeri "created by the pearl fishers of the Gulf Region over 800 years ago" and sung by singers from Bahrain. Although the passion of the fidjeri is enthralling, we are missing its political significance if we don't know that Shawky reserves the fidjeri only for scenes in which the principal character portrayed is Sunni. Perhaps the most rhythmically-stirring fidjeri overlay scenes featuring Sunni and Shia characters at war, such as the measures taken by Sunni warlords seeking to overthrow the last Fatimid caliph of Egypt. One such scene accompanies a gruesome group crucifixion of Shia captives by Sunni persecutors with passionate verse that despite its difficult visualization, superbly conveys the passionate Arab poetic temperament in song.

Had I only grasped my heart in my palm on this brutal day,

I would have taken possession of it,

and held back the flood of tears,

commanding it to cease the deluge

so that it answers the calls of those transient ones.

Does the heart allow a first love to leave its embrace?

I would not blame its naive essence

corrupt desire and illusions always appear upon awakening

pain aches in the hollows of my chest against my ribs

In deference to the sectarian divide between Sunni and Shia, when signifying a Shia character or scene, Shawky switches from song to a recitation of the Shia narration of Ashoura commemorating the martyrdom (shaheed) of Hussein ibn Ali, the grandson of the Prophet Mohammad killed with all the male members of his family in the Battle of Karbala of 680 AD / 61 AH. The narration is voiced by two pilgrims before the Kaba in Mecca, one whom declares he was among those who carried the head of Hussein to Damascus. The sect to which he belongs isn't disclosed, and the speaker could as well be Sunni. Only the recitation of the shaheed of Hussein subtly conveys the narrator is Shia, an identification underscored at the Battle of Karbala with a shot of three glass camel marionettes perform Ma'attam', the Shia ritual beating of the chest in mourning.

There is no question as to the relevance of the massacre at Karbala to the events transpiring in present-day Muslim societies, given that Hussein's assassination at Karbala permanently exacerbates the schism separating Shia from Sunni, from Iran to the United States. Karbala is what determines whether someone is Sunni or Shia. It is the conflict that legislates both at the border and within the state, in the present as it was in the past. Whether or not this makes the Karbala segment, or any other segment of the films overtly religious or is still impartial and historical, Shawky leaves to the interpretation and desire of the viewer, with either way relevant to the open structure, visualization and language of his film.

The greater significance here is that Shawky's historical sourcing of all inter-Muslim conflict is intended to expand understanding beyond its traditional Muslim confines. Shawky could have made his third film without ever referring to Karbala, what with the battle having occurred three centuries before the Crusades and given that each and every mature Muslim knows Karbala is always there in the relations between Sunni and Shia. But his decision to not only include Karbala and the ritual gestures of Ashoura, but to name his film The Secrets of Karbala, indicates Shawky is intent on going to the heart of the conflict. At the same time Shawky is letting the non-Muslim know Karbala is the reason for which the Crusaders' initial successes in Byzantium, Palestine and Syria were not met by a more formidable, unified Muslim resistance, and why in their first order of defense Muslims chose to fight one another before fighting the Crusaders. Shawky, meanwhile, claims to impart no favoritism to one side or the other in his narration. Here is where Shawky's historicism serves him well for shielding him as an impartial historian and dramatist conveying the universal significance of Cabaret Crusades, while at the same time making him attentive to contemporary societies by delineating the genealogies linking the historical conflicts of the medieval Crusades and Jihads to the geopolitical events in the Middle East today.

In this regard, Shawky's predisposition for historical overlapping of the modern and the premodern media can be found to have their parallels in his overlapping of medieval and contemporary Sunni and Shia militarisms--the medieval jihadi he has read about joins in his mind and art with the contemporary fundamentalists of his personal experience. The difference is the genealogy. Shawky confronts our media-induced obsessions with suicide bombers, weapons of mass destruction and institutionalized genocide by openly portraying the reiigiocentric myopia underpinning both Christianity and Islam even before the conflict develops between them. It almost goes without mention that Shawky seeks to displace the circulating myths and stereotypes of a monolithic Middle East in catastrophic and brutal demise by disseminating depictions of the numerous thriving traditions of various ethnicities, faiths, and cultures that are threatened both by an ideological Modernism and any one of the Muslim sectarian supremacy movements. Sometimes the only way to dismantle stereotypes and myths about cultures is to make the stereotyping and myth making about the real diversity that is ubiquitous to a region.

With Shawky's mediation, techniques and motives for his films clearly intent on relaying to audiences the relevance of the historical conflicts of the Crusades and Jihads to contemporary global geopolitics, we might wish to stop here and ask, What Happened to Modernism?

In no uncertain terms, Modernism was terminated with the revelations of Auschwitz, Hiroshima, The Gulags and The Cultural Revolution. These four genocides linked forever in the Modernist ethos as one convulsive death gasp and perpetrated in the name of Modernism between 1936 and 1968 are sufficient to silence any Modernist ideologue still living. Another death blow to Modernism was dealt when Democracy had for many postcolonial societies become overshadowed, first, by Democracy's catalyst, Revolution, and second, when Revolution failed, by a sustained and unrelenting recourse to terror.

But such upheavals as revolution and terror are never sufficient to implementing democracies, especially in societies without developed economies to buffer the effects of passion and desperation. In such cases revolution breaks down into civil wars and dictatorships disseminating the darkest side of Modernism. This is the inconstancy between Democracy, which guarantees freedom of worship without persecution, and Modernism, which marginalizes, even persecutes people of faith. It is the part of Modernism not derived from the Humanism of the Greeks, the Magna Carta or the American Constitution.

Modernism in fact competed against Democracy by advancing a prospective paradigm of 'progress' conditioned on divorcing itself from all 'unverifiable' subjective cultural knowledges -- both those dogmatically religious and vaguely spiritualist. And yet, oblivious to the logic that atheism cannot be any more epistemologically verifiable than theism, the shortsighted Modernist could see in religion only the causes of factionalism, persecution and perpetual warfare, not the quest for the authenticity and benevolence at the heart of society. In this context, Cabaret Crusades can be seen as opposed to the Modernist who remains unreflective of the deeper structural fear of difference, a fear that makes war inevitable among belligerents, including those wars waged by and in the interests of Modernism. Cabaret Crusades by this logic can be best read as an analog between the medieval Crusaders/Jihadis to the modern revolutionary guerilla and terrorist of the Middle East (and elsewhere) intolerant of competing faiths and ideologies.

Taken together, Modernism in the Middle East came to be perceived by Muslims as variously Western, Communist and Zionist imperialisms, and most recently as global corporate imperialisms. Whether their revolutionaries became guerillas or terrorists, each successive generation became better financed, armed, and educated in strategies and tactics than the previous, as witness the progression of terror beginning with the PLO in the 1960s (though modeled after the terror waged by Israelis against the British), and spreading successively to Hamas and Hezbollah in the 1980s, the Taliban and al-Qaeda in the 1990s and 2000s, and today to the self-styled Islamic State of Iraq, Syria and the Levant (ISIL or ISIS). Modernism, parent to weapons of mass destruction, against it own interests, reinvents itself with the revolutionary children of its suppressed colonies.

If this seems a massively burdensome contextualization for a trilogy of films acted by cute marionettes and written and directed by a single open-minded artist, in the case of Wael Shawky and Cabaret Crusades it isn't. Shawky's expert and extensive genealogy of the Crusades and Jihads to the present conflicts of the Middle East bears the weight of such a complex citation of the modern and contemporary geopolitical arena. It also intersects with the demise and global metamorphosis of Modernism that has given way to an epoch by which Shawky's work can be recognized as vitally system-changing, especially in the Middle East. In today's arena of global aesthetics, Shawky's history of the medieval Crusades and Jihads is seen to rightfully challenge the Modernist marginalization of faith-based societies as much as it scrutinizes the faith-based societies for their historical incriminations of reason and free speech. In making the war and terror of the Crusaders and Jihadis his film's deciding principle in the rise and decline of political and religious fortunes, Shawky is participating, whether intently or inadvertently, in a global defense and redefinition of spirituality as an existential response to the contradictions and conflicts of an absurd world unresponsive to the individual and collective wills.

Shawky's upbringing in Alexandria, Egypt, ostensibly confers an intimacy with not just the region but the heterogenous cultures that to this day assimilate the inheritances of the Crusades and Jihads. He has also chosen to augment his experience with the scholarship of Lebanese historian Amin Maalouf's book, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. Both Shawky and Maalouf, from the time that they were children walked in the footsteps of the Crusaders and Jihadis. Such a thorough identification with the protagonists who shaped the history of the region can never be emulated by even the most astute and committed academic student of the Crusades and Jihads in Europe, America and elsewhere outside the eastern Mediterranean basin. This is why Shawky's three films, like Maalouf's book before them, perforate what has been a largely Western Modernist field of study that, even when not deliberately suppressing an understanding of cultural diversity, can hardly be said to have been representative of the Eastern sides of the conflict. And as Shawky's film powerfully underlines, there are many more than two cultural and ideological sides to represent in any study or art of the Crusades and Jihads.

The predominance of Muslim protagonists and other Middle Eastern characters in both Maalouf's book and Shawky's films may alienate Western viewers less keen on the merits of cross-cultural exchange. In fact Shawky, like Maalouf, confers the narratives of Muslim protagonists more richly and at greater length than their Christian and European counterparts. The slight attention paid to Eleanor of Aquitaine (whose amorous adventures in Palestine, and the consequential shifting of her royal possessions, were the cause of 200 years of conflict between the French and the English), and to Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and Richard the Lionheart disappoint viewers accustomed to the Western chronicles of the Crusades. Then again Shawky's depiction of Barbarossa's premature drowning in the Saleph River shortly after his defeat of the Turks is an understated, almost shocking highlight of The Secrets of Karbala. Shawky must include it because Barbarossa' death opened the way for the stream of Saladin's conquests over the Crusader occupiers, given that it was the emperor's formidable army that Saladin most feared. But then Saladin the Sunni Kurd was, is and will alway remain the paramount superstar of the Jihads against the Crusaders, and as he should be for both his unparalleled leadership and his generosity and fairness to those he defeated and conquered. Yet even Saladin's restrained lust for power has negative repercussions today, in that his deposition of the last great Shia Caliphate, the Fatimids of Egypt, further destabilized the balance of power between Shia and Sunni to the present.

Altogether more important than the personal dramas of the historical protagonists are the sectarian disputes dividing both sides. Shawky heaps enormous attention on these disputes with extensive exposure of the corruption that undermines the political and personal agendas and ambitions of the protagonists, setting back the potential development of true faith for Christian and Muslim a thousand years. Of course Shawky's real concerns are the parallel deficiencies in contemporary geopolitical relations centering on the Middle East and its allies and enemies abroad. His films transcend their function as art by challenging the eurocentrism of Western Modernism and the fanaticism of Muslim fundamentalism alike. On another level, Shawky's art is a testament to Modernism's greatest triumph -- its relocation of spirituality within an inspired act of artistic creation intended to resolve, however briefly, partially and personally, the interminable conflict between the human will and the world indifferent to it. In this, Shawky's art is as modern as it is retrospective of premodern cultures, with CONFLICT the deciding principle of Cabaret Crusades . But while his films participate enthusiastically in the Modernist project of Art's confrontation of conflict as spiritual ritual, it also compels us to relive and re-examine through art the spiritualities that made myth of war as a catalyst of spiritual transport in all its ignoble and tragic details.

It is the consistency and universality of war that, despite all modern advances of civilization and re-identifications of the players, makes it possible for us in the 21st century to dismiss the myth that spirituality is the root cause of war and terror. Which means the secular wars and atheistic genocides of recent history enable us to more impartially understand the true causes of war and terror, and especially those wars persistent in the Middle East that claim to have religious ideological and canonical causes to this day, are a fear of difference, the will to power and the requirements of subsistence. In such a climate, Shawky's retrospections on medieval religious warfare, especially those forms that changed the course of civilizations centuries past, have great relevance for recalling and revealing those similarities and disparities of war then and now. In this, Cabaret Crusades is a revelation for our age about the crisis of spirit that proceeds from war and the manipulation and trivialization of spiritualism that ensures an ample supply of sacrificial combatants in the holy war's name.

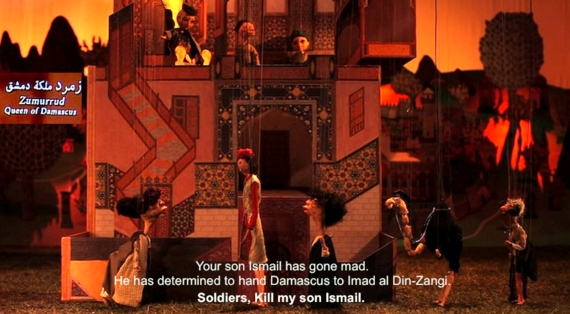

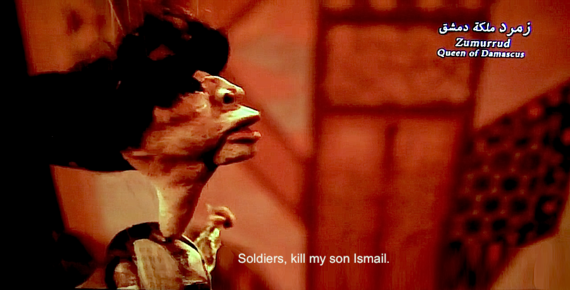

In this capacity, Shawky conveys more dramatically than any history book that the common denominator to all conflicts is the human proclivity to be at variance with the very ideals we purportedly champion and defend as the central guiding principles of our lives. It is such variance from our own beliefs that informs us that such principles are rarely existentially and psychologically in accord with the needs of individuals. In short, there aren't but two antagonistic civilizations at war in the Crusades and the Jihads. There are as many antagonists combatting one another as there are personal interests, with many undermining the very sides they mean to be defended and furthered. Shawky conveys in scene after scene that not even family relations withstand treachery, as we watch brother kill brother, daughter plan father's demise in revenge for her husband's death, even mother kills son for the entitlements of rule, territory and (at least the facade of) faith.

It is such receding division within division within division, not just of the spoils but of the loyalties political, religious and familial, that Shawky, after Maalouf, uses to exemplify the existential breakdown of interests from the collective to the individual. In the end, Shawky seems most intent on chronicling the fundamental contests between the will to power vs. the will to survive which fuels antagonisms and treacheries. It is the most apparent reason that Shawky ends the account in The Secrets of Karbala with the stunted and deranged Fourth Crusade, which never combats on Muslim soil for ending with the sack of the Greek Christian capital of Constantinople by Frankish Catholic knights led by a Venetian Doge. Here Shawky depicts the moment at which the 12th-century Catholic Crusaders, financed by the Venetians, turned their puritanical pogroms on the Greek Christians of Byzantium, when the Fourth Crusade, led by Boniface of Montferrat and financed by Doge Dandolo, killed thousands of Constantinople's citizens, while raping any and all women, secular and nuns.

The next step for Shawky may or may not be the altogether more difficult move -- that of screening his Cabaret Crusades before Muslim audiences in the nations of the Middle East, something about which he has expressed pronounced reservations.

One final note about the presentation of Wael Shawky's film trilogy. In part because the history conveyed in the Cabaret Crusades is fragmentary, anecdotal and elliptical rather than one continuous narration, the artist screens the three films simultaneously in three different galleries, each out of ear's range. Yet with all their formal excellence and historical scholarship, presenting Shawky's films in a galley installation conditioned for a steady flux of viewers is unsuitable to unlocking the deeper cultural meanings being presented. The film's power only surfaces in long sittings through which the narrative, the topical history and the structure of the film together build a world view of intricate complexity and depth. The elliptical editing of each episode and the development of the protagonists central to each requires patience, all of which suggests their best vantage would be home viewing, whether streaming or DVD, where we can pause, replay and navigate scenes at will to facilitate investigation of the issues and to draw parallels to our present.

********************

Four Brief Yet Crucial Turning Points of the Crusades and Jihads for Better Understanding the Cabaret Crusades Films.

For the viewer going into the films with little or no knowledge of the Crusades and Jihads of 1095-1204 AD / 487-600 AH, it will be helpful to know of four crucial turning points of the century-long conflict.

1) In 1095, when the First Crusade was proclaimed in Clermont, France, by Pope Urban the II, Islam had colonized an empire spreading continuously from India to southern Spain. It was in this year that Roman Catholic Christians would set out to liberate Jerusalem and other Christian cities in the Levant. But Catholics also sought more covertly to retake Orthodox cities in the name of Rome. Similarly, Sunni and Shia Muslims competed for the Islamic Caliphate, at times with the aid of Crusaders.

2) Jerusalem and other important cities in Palestine, Armenia and Syria, such as Hattin, Antioch, Tripoli, Acre, Nablus, Tyre and Bethlehem are captured by Christians under Godfrey of Bouillion throughout the late 1090s and held for nearly a century.

3) The rise of Saladin culminates during the Second Crusade in 1195 when he repels the Crusaders and reclaims all territory won during the First Crusade. In Islamic history, Saladin is significant for eliminating the Shia Fatimid Caliphate in Cairo and founding its replacement with the Sunni Muslim Ayyubid Caliphate.

4) Plagued by failure and a long winter before entering Asia, the combined armies of The Fourth Crusade end short of their destination when, desperate for provisions, Boniface of Montferrat is persuaded by his Venetian sponsor, Doge Dandolo, to sack the Byzantine cities of Zara and Constantinople for its treasures. After Christians slaughter Christians, the Ayyubids and other Muslim forces overrun the Byzantine territories to unite all of Western Asia under Islamic Caliphates until the modern era.

On February 27, 2016, the author altered the format of the photo captions to better suit the new Huffington Post blog format. No content was changed.

Listen to the G. Roger Denson talk about Wael Shawky's Cabaret Crusades and other issues in art and culture on Yale University Radio

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on facebook.