The last email that I sent my sister, Brooke, was a picture of my ten-year-old daughter, Jocelyn, dressed in my heels, wearing Ray Ban aviators. Just the picture. No text. Brooke's two-sentence reply was, "Just like you. You're just like mom." It certainly said a lot about Brooke, my mom, my daughter and me. And I loved the fact that we knew what it all meant but didn't have to get into it. But that was it. It probably took all of thirty seconds. When I found out a few days later that she had died suddenly and unexpectedly, I realized that was my last exchange with her. It was a thirty second goodbye. Three months later, in early June, my dad was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He moved in with me, where he lived until he died in August. It was an eight-week goodbye. And that made all the difference.

From the time I was twelve, my father raised me as a single father. He wiped away my tears of teenage heartbreak that were usually reserved for Moms, he strengthened me through the deaths of my mother and my best friend and he had probably suffered more during my painful divorce than even I had.

And, well into his seventies, he cared for my daughter, Jocelyn, while I worked, starting when she was three months old until she began school. He went out and bought his own car seat, stroller, high chair, bouncy seat and a wonder saucer. His once very masculine apartment with it's autographed sports and political memorabilia, perfectly categorized books and movie collections which were once kept in obsessively compulsive neat order, came to resemble a day care center. Sippy cups, bouncy balls, paper princess crowns and houses that he made for Jocelyn's imaginary friend, Jerry, abounded through every room.

And, well into his seventies, he cared for my daughter, Jocelyn, while I worked, starting when she was three months old until she began school. He went out and bought his own car seat, stroller, high chair, bouncy seat and a wonder saucer. His once very masculine apartment with it's autographed sports and political memorabilia, perfectly categorized books and movie collections which were once kept in obsessively compulsive neat order, came to resemble a day care center. Sippy cups, bouncy balls, paper princess crowns and houses that he made for Jocelyn's imaginary friend, Jerry, abounded through every room.

He would limp across the living room with his cane, trying to pick up after her to no avail and finally throw his arms up in the air and just say, "Phooey!" with a big smile. My father was Navy man, a man of organization and routine. But he embraced this enormous distraction to his well-ordered life so robustly that it was breath taking.

It was the very essence of devotion and the very reason why I always assumed that I would move my dad into my home if he were ever really sick.

I knew the challenge would be in convincing him. He'd never seen our lower level because he couldn't handle stairs, so I think he figured our basement was like the ones he'd always known with wet concrete walls and floors and window wells full of leaves and cobwebs.

He loved his apartment with its view of the Potomac river, his computer, his notebooks with his sports statistics, his movies and football games on VCR tapes and his old leather recliner. Mostly, he dreaded the idea of being a burden as much as the thought of giving up his independence. Living in the home of my husband? Under the roof of another man? At one point in the hearty discussions, he insisted that he would pay rent. Rent?

I pointed out that once you factored in my years of private school and college tuition not to mention all the parking tickets that I collected in high school, he had probably covered the down payment on the house. He said he didn't want to talk about it anymore and he wasn't living in my basement.

However, two weeks after his terminal diagnosis, he almost went into a diabetic coma and ended up in ICU. The doctors told him it was time to call hospice and he would need round the clock nursing care. He said he wanted to die and asked me to put him in a nursing home.

I went to his apartment to get the "necessities." Signed photos from Franklin Roosevelt, Truman and Kennedy. Various family photos. A painting of a ship in the Galapagos Islands. And the most important thing, his computer, his lifeline to the outside world. We exchanged multiple emails every single day and I was one of many people with whom he had such frequent Internet contact.

A few days later, my brother, Michael Monroney, Jr. and I brought my dad home by ambulance on a warm summer morning. A few clouds sailed across the blue sky, our hydrangea bloomed like cotton candy so high that you could barely see the front of the house and there was a breeze unusual for June in Washington.

It took two enormous men to get him down the long flight of stairs in a "stair chair." He could walk with a cane but he definitely could not climb back up the stairs. It did not escape my attention that he would probably never leave the basement again.

He walked into his new bedroom unsteadily with his cane. He was very pleased to see the television, his pictures and especially, the computer. I had positioned the desk with the view of the backyard and he peered out the window for what seemed like a very long time. I stood behind him. The sun streamed through the parkland and on to the pool, which seemed to reflect a deeper blue than ever. The pink and white impatiens that always seemed to wither from the DC heat looked alive and stood at attention as if they knew they had a special guest.

I had never seen the backyard look so beautiful. But I had never stopped and looked at it quietly at that time of day or from that angle. Come to think of it, I am not sure I had really taken pause to appreciate it at all. Kids needed juice boxes, towels or band-aids or I was watching them while trying to make a phone call or send an email and, really, I rarely stopped to do anything leisurely.

Finally, he sat down and stared at the computer.

"I can't believe that I can really get my emails here, Sweetheart," he said as began going through the hundreds of emails that he had missed while in the hospital.

"GP! You're here!" Jocelyn, now ten, ran in, hugged him and asked, "Can I get you anything? We have Ritz crackers and... we have ice cream!"

He looked up at her, he looked around the room at his familiar pictures and he got choked up for the first of what would be many times.

I had only seen my dad cry twice in my life. The first time was when his father died. The second time, his eyes welled up was when I was driving off for my freshman year in college, leaving him to live alone for the first time, maybe, ever. Both were notable events in his life.

During the next eight weeks, his eyes watered on a routine basis. When his friends left after visiting, when my daughter brought him a root beer float, when my nephew helped him to the bathroom or when he talked about his own father or a particular memory.

He would get frustrated as the tears fell and tell me, "I am not upset. I have had a marvelous life. I'm just so happy."

It must have been a stunning change for him to go from living the virtual existence of one almost entirely reliant on a computer or television to having so much human contact every day. That, combined with the knowledge that his days were numbered, transformed his experience to a very vivid, personal and no doubt, emotional, one. A root beer float made with love by his grand-daughter, especially knowing that it may be one of his last ones, certainly brought more joy to him than an email.

In his first few days with us, I flitted in and out of his room, fluffing the pillows, adjusting the temperature on the electric blanket, refilling his iced tea or checking his insulin and giving him his medications. Each time I came into the room, I started talking about a particular memory that we shared or I asked him a question about something. He would engage with me but inevitably, his eyes would begin to tear.

One day, passing his room on the way to the laundry, I noticed him staring wide-eyed at the television. When he saw me, he quickly shut his eyes and began a quiet snore.

I doubled back and said, "Daddy. I saw that. You don't have to pretend to be asleep... just tell me if you don't want to talk to me. You can have peace and quiet."

He lips turned up into a slight smile but kept his eyes shut.

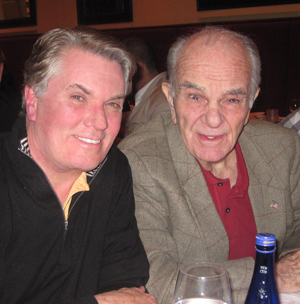

Just then, my friend, Tommy, bounded into the room, "Hi, Mike!"

Dad sprung up at attention, "Hey Tommy," and held out his hand for a firm handshake.

Oh. I got it. He wasn't asleep for Tommy, who never failed to make my dad laugh. My dad didn't want peace and quiet. He was tired of crying. He wanted to be entertained.

My dad wanted to communicate but on his terms. And for once, he was allowing things to be about him.

After one of her visits, Mary, the hospice nurse, told me that she had asked my dad of what he was most proud. She said that he responded, without missing a beat, "My father."

Many people might have listed one or two of their own accomplishments or even their own children, for whom they might take some credit for raising. But my dad had a great sense of humility. He adored his father and strived to live up to his standards of honor, integrity and public service. His pride was always in his father and never his many own achievements.

My dad moved to the District of Columbia in 1938 from Oklahoma when his father was elected to Congress and later to the United States Senate. My dad went to St. Albans school, Dartmouth College, served in the Navy, worked as a reporter for the Washington Post, a Chief of Staff to a Congressman, he worked in the Kennedy Administration, the Adlai Stevenson and the Humphrey Campaigns, and as a Vice President of Government Relations for a company called TRW. He was always engaged in politics and followed every election and every single public policy debate to the very last week of his life.

In fact, last summer, my dad repeatedly said that he was completely at peace with dying except that he did want to see how the elections turn out and he really wanted to see Oklahoma beat Texas this fall. (Which, by the way, they did.)

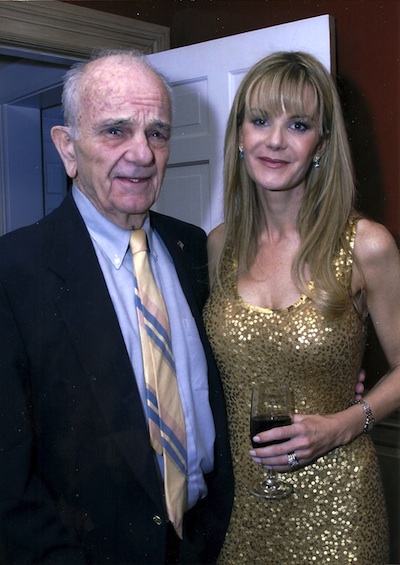

So Dad was in his element when he was able to discuss sports and current events. He loved to talk to people. And when everyone learned that my dad was ill, the response was amazing. It was a magnificent tribute to him. There was a constant stream of visitors in and out each day. His friends. Friends of my late mom's. My friends. There are some people in Washington whom I think are pretty weighty and I know they are very busy, but they came to sit with my dad on multiple occasions and just talk with him.

Tommy visited my dad every single day. He expressed beautifully the way everyone felt, "We all became a lot less important this summer."

Some who came to visit wanted to spend the precious time left with a loved one. Others may have seen the importance of kindness in the face of their own mortality and perhaps, others just wanted to be good friends. Whatever the reasons, we were truly blessed by the love that came into our house all summer.

During the first month of his stay, Dad managed to get outside several times and watch the kids play in the pool. He enjoyed long political conversations with visiting friends. He made his way into the media room and watched Strasburg pitch his opening game. He never did figure out how to operate all the different remotes. In fact, the only people in the house who can do that are the ten- and nineteen-year old. Dad was extremely happy during that time and my husband, Jack, and I hoped he would outlive his prognosis and be with us for another year.

But about a month into his stay, my dad tried to shower by himself. He fell and dislocated his hip. Jack was the first one to the bathroom and managed to get my dad partially dressed. I cannot imagine how humiliating it must have been for my dad. He had to be taken back to the hospital in his underwear and it took three men and many hours late into the night for them to get the hip back in place.

When Michael and I came back the next morning, the doctors told us that our dad should stay in the hospital for another day or so. He lay in the hospital bed and was barely responsive. The room was bare and the view out the window was of the roof of another building. My dad had barely touched the Jell-O that sat on the hospital tray.

"Let's go home," we said.

Another ambulance trip and stair chair ride and my dad was back where he belonged. But he was much weaker. In the days that followed, it was increasingly difficult for him to find the words that he needed to tell his stories. We realized that he must have had a stroke. He loved nothing more than to communicate. We were able to figure out what he needed to do or what he needed to eat but for someone who loved to engage in conversation and tell anecdotes, word retrieval and memory problems were incredibly frustrating.

Fortunately, he had written almost four hundred pages of "Things to Remember" for his grandchildren. He was a magnificent writer, perhaps the best I have ever known. He had recorded interesting experiences and recollections from his life into two binders complete with pictures and footnotes.

Fortunately, he had written almost four hundred pages of "Things to Remember" for his grandchildren. He was a magnificent writer, perhaps the best I have ever known. He had recorded interesting experiences and recollections from his life into two binders complete with pictures and footnotes.

I think that he was sorry that his own father had not done it and not only wanted to pass along the stories to his grandchildren but he also wanted to leave a history lesson.

So my brother and I sat at his bedside, immersed ourselves in the binders, reading aloud from them and asking him to elaborate when he was able to find the words. We had heard some of the stories a dozen times but no one could tell them better than he could. He struggled with specific words but knowing him so well, Michael and I were easily able to find them for him. We all three spoke the language of my dad this past summer.

Michael and his son, my fifteen-year-old nephew, Mitchell, moved in with us. Mitchell stayed on the sofa in the basement media room in order to be close to my dad. Michael rolled out a sleeping bag and slept on the floor in the hall outside my dad's room. After Dad dislocated his hip, it was clear that he could not be alone. Michael and I would stay in his room with him until two or three in the morning and Mitchell would take over until nine or ten a.m.

We all cleared our calendars. We didn't leave the house unless we had to get groceries or go to the drug store. Mitchell might take the dog to the park or go for a skateboard ride but neither Michael or I left Dad's side.

At one point, he looked at us and said, "God, I have the best kids."

Michael replied, "You raised us, Dad."

This embarrassed my dad. He had a sense of humility about him that was endearing. He turned and said to me, "Why is everyone being so nice to me?"

I said, "Because everyone loves you, Daddy. You are a magnificent person."

I think that his whole life, he loved unconditionally. He didn't expect anything in return. He loved his friends because they were his friends. His loved his children because they were his children. When we cared for him in the way that he cared for us, he considered it a privilege and not a right. After the way that he raised us, I think it was his right.

My friend, Jamie, cut his hair for him one day. Afterward, she sat on the stairs and her eyes filled with tears.

"He is shrinking," she said, "They do that, when they get sick."

She was right. He was shrinking. I had not noticed until she mentioned but suddenly it was like half of him was gone. I wondered whether that half was already in heaven. He was sleeping a lot more. He was watching the Nature Channel more often than Fox News.

Jack asked him if he had always watched the Nature Channel and he nodded his head, "Yes."

My brother and I looked at each other. We had never seen him watch the Nature Channel.

He was slowing down from slowing down.

Something changed once he could not find his words anymore. He loved nothing more than to relate to people. And no one could communicate better with children than my dad. From the letters he wrote to me at camp when I was nine, full of stories about my fictitious pet elephant to the songs that he taught my daughter, first and foremost, "Hail to the Redskins." As it became increasingly difficult for him to talk, he started to lose his will to live. He was becoming sick and tired of being sick and tired.

The pancreatic cancer made digestion difficult and the medications took away his appetite for almost everything. But Michael and I could usually find something that he would eat. Until the last two weeks.

"Daddy, I made mashed potatoes. Will you have a few bites?"

He shook his head no.

"A root beer float? Ritz crackers? Aunt Shirley's potato soup? Beef broth?"

No.

About ten days before he died, he had a talk with his lovely hospice nurse, Mary, and it was decided that he did not have to eat anymore. He was done. He had trouble talking. He could not get up to go to the bathroom. Either my brother or my nephew or I had to bathe him. He had lost the will the live. Choosing not to eat was his act of dying.

He had spent almost eight weeks surrounded by his family. My daughter had written him two letters telling him how much she loved him.

"When you picked me up after school, when I saw your big blue car, I knew it would be a good day. I always felt safe with you," she wrote.

His oldest friends visited him and held his hand.

The Rector of Christ Church Georgetown, Stuart Kenworthy, came and spent time with him. He told me that everything Dad said that day was from a deep sense of gratitude and that he was so clearly unafraid of dying. Stuart explained that in the life of the church, that is what they call the "foundation of a holy death" and that my dad was approaching death in the same way that he lived.

The entire time that my dad was dying, he had never uttered a complaint. The multiple insulin checks every day, the pills, the shots, trouble getting to the bathroom, difficulty communicating, constipation, nausea, vomiting and pain. Not one grievance.

Instead, he said, over and over, "I have lived a wonderful life."

And he said, "Thank you."

On Sunday, his eyes closed and he did not open them again.

Over the next day and night, my brother and my nephew sat at his bedside. I lay on the bed beside him. Jack pulled up a chair. We talked to each other and gently talked to him.

I mashed up a raspberry Popsicle and he took it.

On Monday night, his blood pressure slowed.

Early Tuesday morning, I said to him, "Daddy, it is OK. You can go now and be with Mom and Brooke and Grannie and Grampie. It is all right. You can go."

He breathing became labored and he passed away.

While it is a moment for which you pray, a peaceful death, nothing prepares you for it. Even if you have experienced it before, once the moment passes, you cannot help but be overcome by grief. Wait. No, you think. No, it cannot be. An hour ago, he was alive. A few days ago, we were talking. And then, you start reliving all the memories. You are in shock. No matter how prepared you believe you are, it is still mind numbing to lose a loved one. You realize that they will not be there when you want to tell them the good news or maybe cry on their shoulder.

And all the questions begin. Where is he? Is he with my Mom? Will he tell her about my daughter? Will I be with him again someday? And eventually, the questions will subside and the reflection and acceptance begin.

How hard it is to learn that time with a loved one is limited and how quickly tomorrow turns into yesterday. But it seemed that time was suspended during that eight weeks. I rarely found myself thinking about what I would be doing later in the day, that evening or the following weekend. It was about the moment. Was my Dad ok? Did he need pain medicine? Was he hungry? Thirsty? If he was telling a story, I was listening? If the television was on, I was paying attention? More often than not, I was watching him. The pure joy on his face as Shirley Temple sang and danced or the intensity in his eyes as the crew of the Sea Shepherd chased the Japanese whalers was captivating to me.

I learned to live in the moment. Perhaps for the first time. I saw the world through the eyes of a dying man, and it was so much better. Time moved slower, the flowers were brighter, people were kinder, and my family and friends were more meaningful. I can only hope, as a legacy to my dad, that this vision can endure.

I had an eight-week good bye and it did make all the difference.