Invitations to designer shows during New York Fashion Week are harder to come by than smiles on the catwalk. There was once a time, though -- long before models perfected their "I'm too cool for the world" pouts -- when you couldn't pay people to show up for this biannual orgy of style.

It was 1943, and a petite blonde public relations veteran named Eleanor Lambert had conjured the event as a scheme to overthrow Paris as the world capital of fashion. Only 53 of the 150 journalists that she invited bothered to attend, however, even after Eleanor offered to pay their expenses. At the time, French couturiers were world famous celebrities, while American designers were unknown. Clothing labels in the U.S. only carried the names of manufacturers, newspapers didn't feature fashion pages, and few reporters cared about the subject beyond their own closets. One afternoon during that first Fashion Week (known then as Press Week), while riding in the elevator of a Seventh Avenue showroom, Eleanor overheard two out-of-towners talking. "One of them said to the other, 'Are you going to so-and-so's collection?' And the other one answered, 'No, his clothes don't fit me," recalled Eleanor, who died in 2003 at 100, in an oral history for New York's Fashion Institute of Technology.

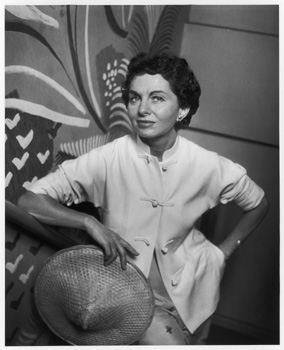

Eleanor Lambert in 1963, AP photo

Ever since the seventeenth century, when Louis XIV invented a standard of luxury dressing that demanded rules and endless reinvention, France had ruled Fashion. Beginning in the 1900s, U.S. designers, manufacturers, buyers and journalists made the twice a year pilgrimage to Paris to witness the city's couture openings. What they saw determined the silhouette, colors, skirt lengths and accessories for the next season. American women, too, were hooked on French clothes, either the real things or knock-offs.

But World War II had totally cut off America from France. New York, which had always had a thriving apparel industry, was the logical successor as Fashion's capital, and the city's garment unions, clothing manufacturers and department store executives saw their golden opportunity. They formed the New York Dress Institute and set up an agreement stipulating that one half of one percent of the cost of every union dress would go into a fund for advertising American clothes. They turned the money over to the J. Walter Thompson Agency, which came up with billboards and magazine ads showing a drab, defeated looking woman with a caption that blared, "Aren't you ashamed you have only one dress?" Another ad, meant to spark patriotic impulses, portrayed maimed and dying soldiers at Valley Forge looking longingly at an overdressed Martha Washington.

The ads were inane and tasteless, and executives at New York's leading department stores were appalled. They needed a new image. They needed Eleanor Lambert.

To say that Eleanor was the most important figure in the history of American fashion is probably an overstatement, but only just. If she hadn't existed, fashion would have had to invent her. She was the first fashion publicist and also the first to promote American designers as Picassos of style, artists who deserved as much acclaim as the stars of French couture.

The daughter of an advance man for P.T. Barnum & Bailey's circus, Eleanor grew up in genteel poverty in Crawfordsville, Indiana, dreaming of a glamorous life beyond her town's small minds and large Victorian houses. She studied sculpture at the John Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis and started her career in New York as a publicist for artists such as John Curry, George Bellows, Morris Ernest and Isamu Noguchi.

Then in late 1934, Eleanor made a contact that would change her life. Impressed by publicity Eleanor had arranged for an artist, New York fashion designer Annette Simpson phoned to ask if Eleanor would do the same thing for her. Eleanor began cultivating designers as she had artists, and soon she was representing the top figures in American fashion: Bonnie Cashin, Claire McCardell, Norman Norell and Hattie Carnegie.

Bonnie Cashin

Claire McCardell

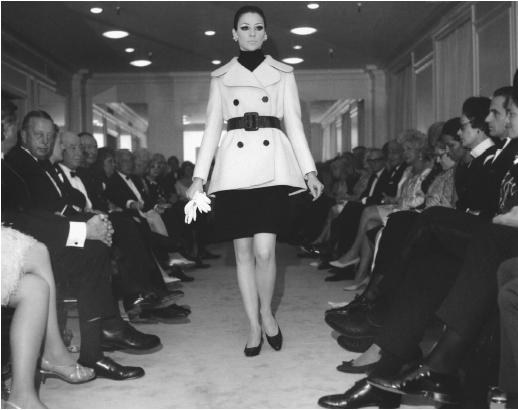

Normal Norell show in fall 1968

Mrs. William S. Paley in Hattie Carnegie

When the Dress Institute hired Eleanor in the summer of 1940, the first thing she did was tell the manufacturing and store executives to start promoting their best designers. They chose eleven names, including McCardell, the wildly talented originator of the wrap dress later popularized by Diane von Furstenberg, and Mainbocher, the Chicago-born French couturier who had fled Paris for New York at the start of the war. Eleanor called them the Couture Group and to publicize them, she came up with three ideas that became enduring American fashion traditions.

The first was the Best-Dressed list, which continues today under the auspices of Vanity Fair; the second was the Coty Awards, the precursor of today's Council of the Fashion Designers of America Awards; and the third was Press Week.

Eleanor's publicity push paid off. Throughout the war, the women's pages of the nation's newspapers were full of stories about how New York was replacing Paris as the global fashion leader. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia had their pictures snapped sewing American designer labels into clothes, and the mayor touted homegrown talent whenever he could. "The only reason Paris set styles all these years was because the buyers like to go there on holiday," he told one reporter.

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia

It was as if by insisting it was so, he could will New York into overtaking Paris. After the war, however, Paris made a stunning comeback with Christian Dior's New Look, a regressive style of cinched waists and voluminous skirts that recalled a vanished era of corsets and crinolines.

Still, the French never fully regained their pre-war sartorial magic. France's rule over Fashion, after all, was based on haute couture, a tradition that existed for a handful of rich women who made a career out of dressing. Couture was an art, a luxury, an ideal from which more affordable clothes flowed, and it became increasingly irrelevant as time went on.

Through it all, the tradition Eleanor Lambert started of a week long showcase of New York fashion that would twice a year bring to the city designers, consumers and journalists from around the nation, continued. At first it was held in one Seventh Avenue building, "with everyone making treks up and down the elevators," Eleanor recalled. As its popularity grew, it moved to a large movie theater on Sixth Avenue in the garment district and later to a hotel auditorium uptown, with such top designers as Calvin Klein and Donna Karan holding runway shows in their own ateliers.

It wasn't until 1993 that the event, under the auspices of the Council of the Fashion Designers of America, was brought together in one centralized spot under the big white tents at Bryant Park -- a location it has since outgrown, sparking a projected move next spring to Lincoln Center.

In recent decades, the popularity of Fashion Week has been fueled by the red carpet, celebrity brands, TV shows like "Project Runway," and fashion web sites. The New York event has sparked an explosion of imitators, and today nearly 100 cities around the globe from Auckland and Berlin to Reykijavik and Sarajevo hold annual or biannual fashion weeks.

French couture hangs on, but just barely, and mostly as the anachronistic habit of a few aged billionairesses. Every year the roster of couture houses shrinks, and today only a handful are left. Meanwhile, Milan is strong, as new markets in Beijing and Mumbai rise. But New York reigns supreme.

The Ralph Lauren Fall 1995 fashion show in New York, Getty photo