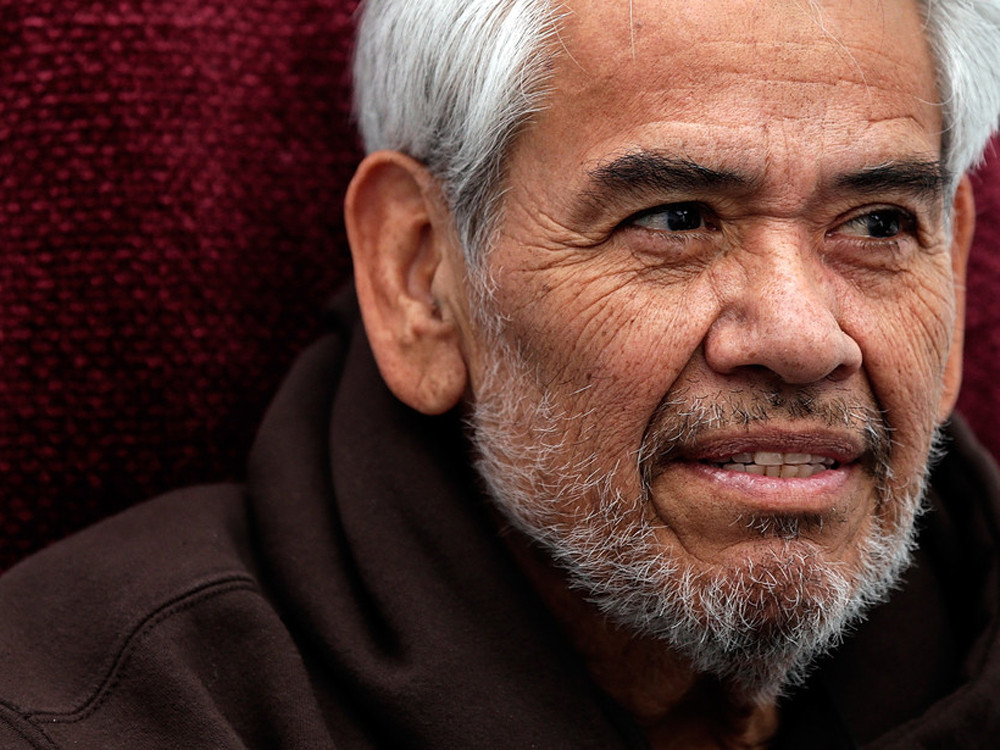

Eliseo Medina is a relentless optimist. The 67-year-old activist has a genial demeanor and a calm, unassuming way about him -- qualities that have served him well during his decades-long career pushing for workers' rights and immigration reform. When you're fighting uphill battles, it helps to remain positive.

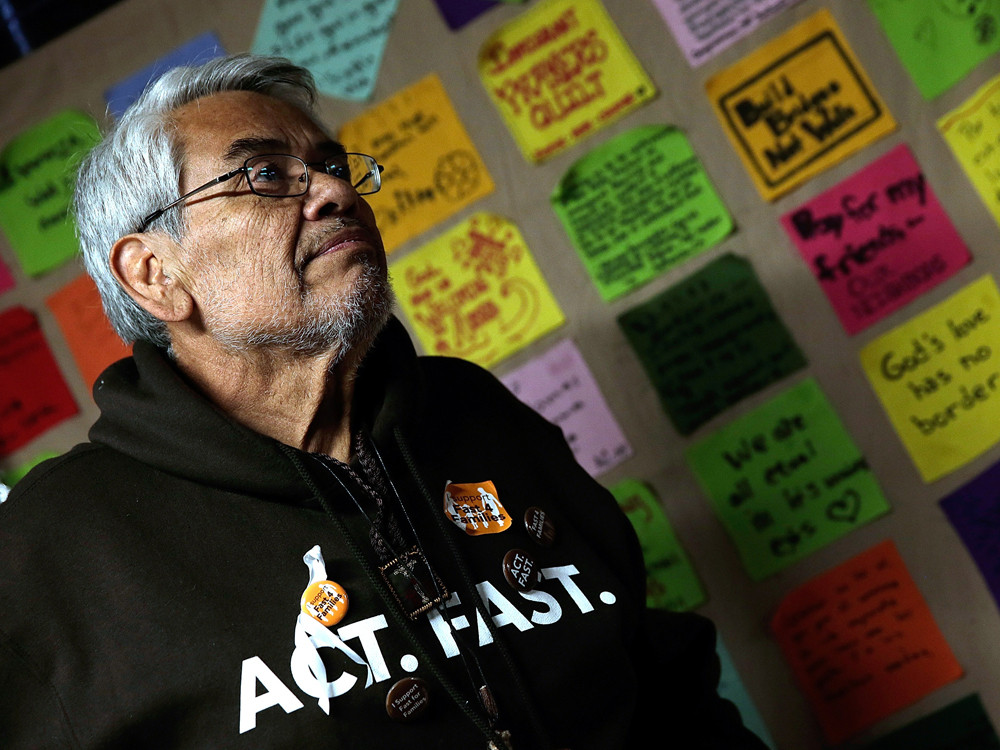

By the end of last year, however, even Medina was losing patience. Since retiring from his post as secretary-treasurer of the Service Employees International Union in September, he had devoted himself to the immigration reform cause, full-time. Two weeks before Thanksgiving, he left his wife and children at home, moved into a tent on the National Mall along with a small group of supporters and started fasting in an effort to draw attention to the reform movement, which had stalled in Congress.

The lack of food was making Medina dizzy and weak. And despite his efforts, there appeared to be little hope of convincing Republican lawmakers to move forward with an immigration reform bill. Even starting a dialogue was proving impossible. Medina and his supporters had asked repeatedly to meet with House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) to discuss the issue, but their requests had been ignored.

On Nov. 19, seven days into his fast, Medina and his fellow advocates decided to escalate matters. A group of about 50 people trekked up to Capitol Hill, filed through the metal detectors in the Longworth Office Building and assembled in front of Boehner's office.

Brittany Bramell, Boehner's spokeswoman, positioned herself outside of the office door. She dutifully promised to pass along the letters and statements the protesters had brought with them, stories of families separated by deportation and border-crossers dying in the desert. But Medina was persistent in asking for a meeting with the Republican leader.

"What about tomorrow?" he asked. "Next week?"

"All we were asking is for a conversation, and yet Speaker Boehner closed his door, closed his office," Medina recalled recently. "In my mind, I said, 'What are they afraid of?'"

It wasn't supposed to have come to this. The 2012 election results were supposed to have convinced Republicans of the political necessity of passing immigration reform. Numerous GOP officials, senators and more nationally-ambitious House members said it was an electoral imperative. That logic has escaped most House Republicans, however, who are betting that blocking immigration reform will help more than hurt as they vye for reelection this year.

In response, immigration reform advocates have staged increasingly dramatic lobbying efforts. Undocumented immigrants have come out of the shadows, activists have chained themselves together outside deportation centers and others have infiltrated detention facilities to expose conditions there. Pushing immigration reform has become a decidedly risky business.

These actions helped call attention to the dire circumstances many undocumented immigrants face. But in the end, they did little to advance a legislative solution in the House. Medina decided to push Congress one last time to take action. All told, he went without food for 22 days, a powerful protest that helped save immigration reform from being forgotten in Washington.

"I thought that if we didn't do something that it would basically die from neglect," Medina said. Four other activists participated in the fast for three weeks, like Medina, and many others joined the protest for shorter periods of time. "We could keep talking about immigration reform, but we would be talking to ourselves," Medina said, "because for all intents and purposes the policymakers would feel they were successful in talking it to death."

"More than anything else," Medina said, "our hope was to really create an urgency to this issue to ensure that they understood that this issue was not going to go away."

Lawmakers may be starting to get the message. Fewer than 48 hours after Boehner's office rejected a meeting with Medina, the House speaker began signaling that he would move forward on immigration reform. Last week, House Republican leaders introduced a set of immigration reform principles, including giving legal status to some of the nation's estimated 11.7 million undocumented immigrants -- not the path to citizenship Medina and others were calling for, but a huge step considering concerns that the House GOP would pass over undocumented immigrants completely. And during his State of the Union address, President Barack Obama called on House Republicans to work with him to get immigration reform done this year.

"We put immigration reform back on the front-burner," Medina said in December, sipping a strawberry smoothie in an office at SEIU headquarters in Washington. "Before that, everybody said, 'Immigration reform is dead, it's not going to happen.' Now the conversation is, 'When is it going to happen?'"

In 1956, at the age of 10, Medina immigrated legally from Mexico to Delano, Calif. There, he joined his father, who worked as both a temporary worker under the Bracero Program and also as an undocumented laborer.

"I've been living in the immigration system since before I was born, because of my family history," Medina said.

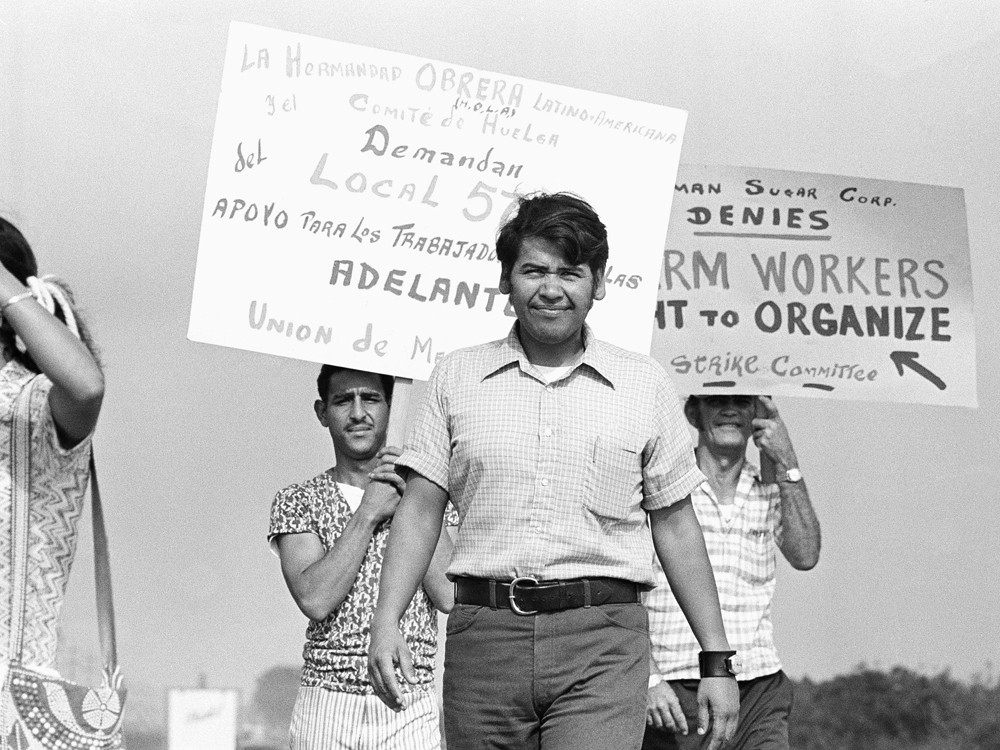

He quit school after eighth grade to work full-time, picking tomatoes, grapes, oranges and peas. By 19, tired of the conditions in the fields and having discovered that he was a terrible judge of tomato ripeness, Medina scrounged up the money to become a member of the United Farm Workers, led by activist Cesar Chavez, in 1965.

Before long, Medina became a full-time organizer with the United Farm Workers and eventually rose through the ranks to become the union's vice president. During that time, he held pray-ins at Chicago supermarkets over conditions for laborers who picked grapes, and traveled to Florida to organize workers there. But he was still a legal permanent resident, which meant he was prohibited from union organizing under Florida law. In 1974, he gained U.S. citizenship.

"I was 27, and I had not really gotten involved in the civic life of this country, I had just been in my own little Spanish-speaking world," Medina said. He hasn't missed an election since.

He surprised almost everyone when he resigned from the United Farm Workers in August 1978. Tensions with Chavez were partially to blame. Medina wanted the union to bring on more full-time staff rather than rely on volunteers.

"That was not something that Cesar was interested in doing," Medina said. "It got to a point where I decided I needed to go off and do something else."

Medina went to work that year for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees in California, and then on to the Communications Workers of America in Texas.

In 1986 he was on the move again, this time to the SEIU. Though comprehensive immigration reform hadn't been a central component of his work to that point, he soon helped convince the AFL-CIO, of which the SEIU was then an affiliate, to adopt legal status for undocumented immigrants as a tenet of its platform. It was a shift for labor politics, which had long harbored concerns that immigrants take workers' jobs and lower their wages.

"It always struck me as kind of odd that [unions would] look at immigrants as people who were competition rather than allies," Medina said.

During the decades he spent as a labor organizer, Medina came to appreciate how bold displays of advocacy could move political considerations. Chavez, his early mentor, had fasted multiple times to spotlight labor struggles, going without food for 25 days in 1968, 24 days in 1972 and 36 days in 1988. His actions drew national attention. Then-presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy came to Delano, Calif., in 1968 to join Chavez for the end of his fast. In 1988, Rev. Jesse Jackson took up Chavez's cause for better treatment of farm workers and went without food for three days after Chavez ended his fast. He was followed by celebrities and political figures such as Carly Simon, Kerry Kennedy and Whoopi Goldberg.

Prior to 2013, Medina had fasted twice. As a 28-year-old in 1974, he went without food for 13 days in an effort to convince people not to buy grapes or lettuce due to the poor conditions for the workers picking them. The effort helped the United Farm Workers push successfully for a collective bargaining law in California the following year. Medina conducted his second fast in 2006, when he spent 11 days abstaining from food in solidarity with University of Miami janitors who were fasting as well. That push helped produce a settlement with the cleaning contractor that allowed the janitors to unionize more easily.

Last year, comprehensive immigration reform seemed to be within reach. Yet a seemingly never-ending series of press conferences and letter-writing campaigns failed to loosen the logjammed legislative process. By late October and early November, reporters were writing obituaries for immigration reform. Politicians were banking on the pro-reform lobby campaign eventually petering out. Something dramatic was needed.

Medina decided it was time for him to fast again.

On Nov. 11, Medina sat down to eat one of his favorite breakfasts: eggs with tortillas and salsa. It was the last food he would consume for the next three weeks.

Fasting for a day or two, or even greater lengths of time, isn't necessarily dangerous. The longer a person goes without food, however, the more they deprive themselves of the nutrients their bodies need to function. They lose weight and muscle mass as their bodies convert it into glucose and ketones for the brain. Eventually, vital organs such as the liver and kidneys can suffer damage.

Even at 67, Medina wasn't too concerned about the potential consequences fasting could have on his health. To him, mental preparedness is more important than physical readiness.

"For me, it's all in the mind, that if you haven't really decided that you're going to do it and that you have a reason for doing it, you'll have a really difficult time," he said. "Because then your mind isn't really controlling your body, and so the hunger pangs and all of that are horrible, and you feel nauseous and you get headaches."

Still, before embarking on his fast, he got the support of his wife and children and consulted a doctor. "I wanted to do it, but I also don't have a death wish," Medina said.

His previous fasts had also taught him that it was important to rest and conserve energy, and that it was easier to fast with a group than alone.

On Nov. 12 on the National Mall, Medina began his vigil, officially called the Fast for Families, along with Dae Joong Yoon of the National Korean American Service & Education Consortium, Cristian Avila of Mi Familia Vota and Lisa Sharon Harper of the Christian social justice group Sojourners. They were joined by more than 100 supporters over the course of the fast, including Rudy Lopez of the Fair Immigration Reform Movement, who started later but also fasted for 22 days total. During the day, they would share their own personal immigration stories with visitors and lead prayers for immigration reform. At night, since National Park Service regulations prohibit sleeping on the Mall, volunteers would man the tent so Medina and the others could rest at a nearby hotel.

For Medina, the second day of the fast was the hardest. He started craving food -- mostly huevos rancheros, sometimes pizza -- and had trouble stopping himself from thinking about it. The churning in his stomach was painful. But the hunger pangs went away quickly, he said. What was worse was the weakness.

Normally a quick riser from his bed, he found that he had to move cautiously to start his days. There were portable toilets about 200 feet from the tent, but even that short walk became exhausting. At times, Medina's vision would go gray, and he'd feel dizzy. Once, about 15 days in, Medina passed out briefly.

By the end of the fast, he'd lost about 25 pounds from his 5-foot-9-inch, 188-pound frame. His eyes looked tired under his wire-rimmed glasses.

"If you know Eliseo -- he's tough," Rep. Xavier Becerra (D-Calif.), an immigration reform ally, told The Huffington Post. "I could imagine what he was like at a negotiating table. He was tough, and he was a pitbull on the issues he cared about. But during this process, I saw another side of him, a very devoted side where he was willing to sacrifice his health for this cause. ... He looked a lot more frail than I've ever seen him, and to me that showed he was willing to sacrifice in ways that I'd never thought before." Along with the protesters, House Democrats like Becerra were also growing impatient. They had introduced a bill in October based on the Senate-passed legislation and, despite picking up three GOP co-sponsors, were still waiting for a vote. Rep. Joe Garcia (D-Fla.), a lead sponsor of the bill, invited the fasters to come to the House gallery on Dec. 2. The group watched as Garcia gave a speech calling on Boehner to bring the legislation to the floor.

"It's unfortunate these brave souls are suffering in the name of immigration reform," Garcia said, referencing the fasters sitting in the gallery above.

Their protest gave the reform movement a "second wind," Medina said. Numerous lawmakers stopped by the tent to express their support. Twenty six members of Congress, all Democrats, even joined the fast in solidarity for 24-hour periods, including Garcia, New Jersey Sens. Bob Menendez and Cory Booker and California's Zoe Lofgren, the top Democrat on the House's immigration subcommittee.

"The Democrats went from passive supporters to actual champions of immigration reform, because they understood what it meant," Medina said. "A whole bunch of them were fasting as well -- when was the last time you ever heard of congressmen fasting?"

On Nov. 29, Medina and his fellow activists received a surprise visit. When the flap to the tent opened, President Obama walked in, followed by Michelle Obama. Over the better part of an hour, Medina and others talked about their lineage, what immigration reform meant for them and the state of their fast. The mood was relaxed, Medina said, but emotional. A few of the fasters relayed that the first lady teared up while listening to the stories of those in the tent.

"It was just a group of people who were talking about an issue that really mattered to them," Medina said.

Medina asked the president to lead them in prayer. He recalled Obama praying for the people suffering under the current immigration system and for the fasters pushing for reform.

At one point, the president suggested that it might be time to let others take up the task. He and Michelle expressed concern about Medina's well-being, citing his age. "I guess they thought a couple of us were little bit older and perhaps a little more fragile," Medina said. A few of the fasters, including Yoon, had been hospitalized, and two others who had been fasting for shorter periods had been forced to quit.

Doctors and nurses who had been monitoring the health of the protesters shared the Obamas' concerns. They told Medina and the others that they needed to stop in order to avoid major organ damage. He bowed to their advice.

"Other than the doctors telling us we couldn't, mentally I could have gone much longer," he said. Back at their hotel, Medina and the other 22-day fasters sat down in their rooms and drank chicken broth in tiny sips.

It "tasted wonderful," Medina recalled.

On Dec. 12, the Fast for Families officially came to a close. The same day, the House of Representatives took its last votes of the year and left town without pursuing immigration reform.

Considering the circumstances, advocates have cause for concern. Even if Boehner allows votes on piecemeal immigration reform bills, they may not have the support to pass. Getting a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants is looking especially difficult. Twenty-two days without food and all the emotional and physical turmoil that entailed may have saved immigration reform from falling off the political radar, but it's not enough to get a bill through a deeply divided Congress.

There are glimmers of hope, however. Since the fast ended, the House GOP moved -- slowly -- toward announcing its plans for immigration reform. On Jan. 30, Boehner pitched a series of principles on immigration reform to GOP members at a retreat. They included allowing undocumented immigrants to "live legally and without fear in the U.S.," a notable shift from a year ago, when many House Republicans were refusing even to talk about what should be done about the undocumented population.

"The good news is that it's on the radar screen," Medina said earlier in January. "Any time people are moving forward, it's progress."

And immigration activists have no intention of giving up. They plan to continue pro-reform actions elsewhere, in congressional offices around the country and at detention centers.

Medina has even decided to fast once more. Starting on March 5, Ash Wednesday, he will spend one day a week without food until the end of Lent. In addition, as the next phase of the Fast for Families, he will join a bus tour to call for immigration reform. They are anticipating making stops in about 100 congressional districts.

Medina said if legislation were to pass, he "would consider it a crowning achievement" of his life's work.

"When you start getting to the end of your career, you start focusing on what's most important to you," he said. "For me, immigration reform is the most important thing that I wanted to do."

Additional reporting by Sam Stein.