She made her name with a memoir that captivated the world and cemented her place in literary history. Then she wrote another -- and drifted even further from the thing she most loved to do. Now, the author of Eat, Pray, Love returns to her fiercest passion, with a book she's spent her entire life preparing to write.

By Katie Arnold-Ratliff

If you're ever scheduled to visit Elizabeth Gilbert at her rambling yellow Victorian in tiny Frenchtown, New Jersey, and you think that the area's unmarked rural roads may have turned you around and delivered you to the wrong driveway, two sights will confirm that you're in the right place: first, the half-dozen stone Buddhas lounging in the grass around the front porch; and, second, the slender blonde who will be sunnily striding toward you, calling your name like you're old pals, introducing herself as Liz and thrusting a sprig of herbs into your hand. "Taste this," she'll command. You'll bruise a leaf between your teeth, and it'll savor of lemon, and you'll feel slightly bemused -- what's this lady's deal? -- but there won't be time for bemusement, because here come two cats who'd very much like you to pet them, and also a dog pawing at your knees, and your new old friend is ten steps ahead of you on the stone path to her house, and did you want a cappuccino or a latte?

Which is to say that the bewitching, headlong experience of hanging out with Gilbert is a lot like her bewitching, headlong books: fun, infectious, alternately goofy and deep, full of lovely things to eat. Eat, Pray, Love, her 2006 memoir, saw her bounding across continents, tumbling through love affairs, somersaulting into every big existential question ever asked. Throughout, Gilbert deployed her winning wit -- and startling candor. She invited the reader into the upstate New York bathroom where, curled on the floor, choking on sobs, she asked God to help her quell her anguish; she cracked open her marriage to reveal its withered insides; she spoke, in the span of a few hundred pages, of her fits of rage and fear, her suicidal thoughts, her freak-outs in yet more bathrooms ("Always the bathroom!" she wrote), her urinary tract infections occasioned by an excess of hot sex. She laid bare her life -- every piece of it -- and millions of readers took in the view.

Gilbert, 44, had written a 1997 story collection, Pilgrims, and a 2000 novel, Stern Men, and a 2002 biography of naturalist Eustace Conway, The Last American Man -- but it was Eat, Pray, Love that became a cultural juggernaut (and a Julia Roberts film), that made Gilbert a literary superstar, and that inspired a 2010 follow-up, Committed, in which Gilbert went through the whole soul-excavating process again, this time documenting the harried circumstances of her remarriage. As her loyal readers know, Gilbert found a happy ending in Eat, Pray, Love with "Felipe," the Brazilian who is now her husband (and whose real name is Jose Nunes).

But if you assumed Gilbert's next book would be another memoir that bivouacs on the best-seller lists for years on end -- if you assumed, in other words, that she would plunder her private business one more time and serve it up for massive profit, endlessly reinventing her own lucrative wheel -- you'd be wrong.

Instead, Gilbert has left memoir behind to dive headfirst into the gaslit era of scientific inquiry and seminal literature, of Charleses Darwin and Dickens. She has pored over 19th-century shipping manifests and 18th-century travelogues; has tiptoed, pen in hand, between the age of enlightenment, with its unearthing of nature's mysteries, to the thrilling dawn of the Industrial Revolution. She's been dampened by the spray of Tahitian waterfalls, felt the cobblestones of Philadelphia's streets press into her soles, climbed the spiral steps of the herbarium at Kew Gardens. She's pushed her fingers into woolly wealths of moss. She has mulled, from the confines of her desk, the correlations of nature, the principle that connects a grain of sand to a galaxy, to create a character who does the same -- who makes the study of existence her life's purpose. And in doing so, Gilbert has written the novel of a lifetime.

"This is asparagus," Gilbert says of a cluster of spiky three-foot stalks standing sentry over the herbs, tomatoes and greens in her lush garden, each bed of crops framed by gray paving stones. In place of the previously proffered herb (sorrel, it turns out), she now totes a basket of uprooted weeds, moving past the lavender and the tulips and around the front porch, stepping over a spill of cherry blossoms and kneeling beneath her clothesline. "This is my moss garden," she says; at the moment, it's a few plastic containers of green-black fluff, but Gilbert's reverent tone indicates their potential.

Her home is strewn with tchotchkes (a wooden horse puppet, a painting of a TV hung beneath the TV, four dried purple allium blooms in an old milk bottle). The kitchen's window seat is carpeted with dog hair (it's a favorite hangout of her doe-eyed mutt, Rocky), and the floorboards groan. At the gleaming stove, the storied Nunes, Gilbert's husband of six years, is making breakfast. Silver-haired and bespectacled, he wonders aloud how many eggs he should cook. (Ask for one and he will deliver two, saying, "I made an executive decision.") He describes how, at a friend's cookout the evening before, a whole pig was spit-roasted. "They also served chicken," Nunes jokes, "for the vegetarians." Gilbert crouches to lament the state of Clifford, the very sick old tomcat who earlier barfed in the foyer, consoling him with a fingerful of cappuccino foam. In a pair of baskets, cats Zipper and Millie nap and stretch the morning away.

Above the first and second floors, but below the tiny crow's nest with its 360-degree windows, is the room that would be an attic if Gilbert hadn't had it transformed into a low-ceilinged study, with a central beam wrapped in tree bark and bookshelves carved to resemble twigs and vines. She calls the room the skybrary. The staircase leading up to the space is painted with a line from Emily Dickinson, one word per step: "The soul selects her own society -- then shuts the door."

This is where Gilbert wrote her new novel, The Signature of All Things, the sweeping story of Alma Whittaker, a frank-tongued and plain-faced girl born in 1800. When Gilbert says, "I think a really large part of how the novel turned out has to do with where it was written," the room is reframed: The small windows are like portholes of a ship -- perhaps like the one that took Alma to Tahiti; the book-lined walls are from the library where Alma feverishly studied Latin and astronomy; and the hulking wood desk, made from a smoothed slab of acacia, is the place where Alma applied herself to the study of moss variants Neckera and Pogonatum. Here's a file adorned with an image of Charles Darwin, whose work makes a cameo in the story, and here are rows of books about the history of Philadelphia, and herbaceous plants, and Beatrix Potter, a naturalist whose era overlapped with Alma's. Here are several colorful boxes, each filled with a thousand or so notecards. (In ninth-grade social science, Gilbert learned to do research by writing one fact on each card, allowing her to reorder them at will.) Here, in other words, are the raw materials of Alma Whittaker.

Today Gilbert resembles, if not quite a contemporary of Alma's, then someone plucked from a similarly distant time. Her green skirt falls to her leather boots, which she removes to sit cross-legged on the low bed in the skybrary's corner -- "my favorite part of the house," she says. Barefaced, she's pinned her scribbly hair behind her ears, and now she presents the object that inspired the novel.

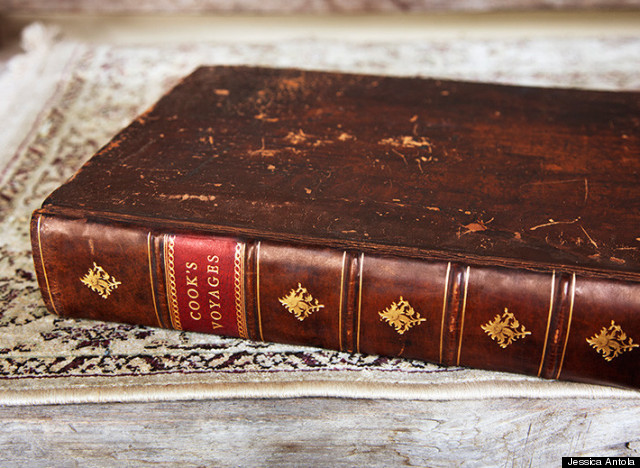

It's a massive old book, its leather binding rubbed raw in places, its spine embossed with gilded leaves and the words Cook's Voyages. The lifting of its cover produces a crisp snap, and its heavy pages weigh it open. Within them live dense blocks of type, ink drawings with lines fine as spider legs and the warm scent of ancient paper. The book was a gift from her great-grandfather to her father, a Christmas tree farmer in rural Connecticut. "It's way nicer than anything my family should have had," Gilbert says -- which is why, as children, she and her sister were forbidden to touch it. And yet at some point during her childhood, she claimed it as her own: Scrawled in childish lettering on the book's front leaf is a ballpoint inscription that reads "Elizabet."

The volume is a 1784 travelogue of Captain James Cook's far-flung voyages through the tropics and beyond. When her mother moved a few years ago, she discovered what Gilbert had written, at which time she gave the book to her, saying, "I guess this belongs to you." Something in Gilbert stirred. The book had captivated her all her life -- and now it seemed to glow with possibility.

"Creativity is a scavenger hunt," she says, the book filling Gilbert's lap. "It's your obligation to pay attention to clues, to the thing that gives you that little tweak. The muses or fairies -- they're trying to get your attention. Something was saying I needed to pay attention to this book."

At first Gilbert thought, "I'm a traveler. I'm supposed to re-create Captain Cook's voyages around the world. I'll have to get my hands on a boat!" Except that book had already been done and it was called Blue Latitudes, by Tony Horwitz." Next, Gilbert thought, "Okay, don't travel the world. Do the opposite." We'd just moved to Frenchtown and I thought I'd write about staying put. Learn where I was in intimate detail. And as I started to write a proposal, I came upon a book that was exactly that idea."

These setbacks convinced Gilbert it was time to take a break, which suited her fine. "I was starting my garden," she says. "And all I wanted to do was know about those plants. That's how it began. I was, like, "It's not an adventure story -- it's a botanical story." Cook's presence in the novel extends fewer than 20 pages. He was just the beacon Gilbert followed toward something greater.

In The Signature of All Things, Alma is the child of Henry Whittaker, a blustering botanist and pharmaceutical magnate, and Beatrix, his stern Dutch wife. As the inquisitive Alma comes of age on her family's Pennsylvania estate, she is raised on tales of Henry's wild adventures with the legendary Captain Cook. She frequently runs afoul of Beatrix's austere social strictures. She develops an abiding love for the natural world. But she finds herself constrained by the reality of her time: She is female, destined to spend her life housebound. Alma does her best to indulge her vast intellect with Henry's equally vast library, mastering every subject she studies, inheriting her father's interest in flora and drawing, as botanists of the era did, exquisitely detailed renderings of plants.

And then, in a field of limestone boulders, a 22-year-old Alma stumbles upon something even more exquisite: dense thatches of moss, each a bustling ecosystem unto itself. Over the ensuing decades, Alma becomes a leading bryologist, combing through these teeming landscapes: "This was a stupefying kingdom. This was the Amazon jungle as seen from the back of a harpy eagle," Gilbert writes. The discovery ignites something in Alma, and the rest of the novel sees her evolve into a woman of daring, one who takes control of her father's holdings, falls in love (and gets her heart broken), and visits some of the planet's most distant reaches, ultimately arriving at a scientific theory that rivals those of her era's greatest minds.

"My initial idea was that she was never going to leave her father's estate," Gilbert says. "I wanted to write about what a woman with that much intellect, creativity and energy might do to sublimate her ambitions. I've always believed any talent you have that you're not capable of using becomes a burden, that it metastasizes."

It's hard not to wonder if this statement is autobiographical, a reference to Gilbert's break from fiction -- her first literary love, she says. Imagine writing a book you expected few people to read. And then the whole world read it. You would become, in the eyes of others, inextricable from that book, prompting them to want that from you again and again. It would be difficult to deny the demand.

Or worse, imagine never being able to write at all. In a sense, Gilbert's work honors the long roster of women in history whose sex restrained them -- who never saw what lay beyond their front gate. Gilbert recalls how her great-grandmother, who barely left Pennsylvania, marveled that she went to India, Indonesia, the Andes. The Signature of All Things is an offering to women like her, and Alma is an embodiment of them, as real to Gilbert as her kin. "When I was writing the end of the book," she says, "it was through sheets of tears and snot. I love her so much. There's nothing you could do to convince me that Alma's not an actual figure in history."

Had she lived, Alma would likely not have "gotten on a ship and sailed," as Gilbert let her do -- which Gilbert knows. "I wanted to rewrite the 19th-century women's novel, which had only two possible endings: You get married or you're ruined by a sexual or social error. You get Pride and Prejudice or Anna Karenina; you're living in the big mansion with Mr. Darcy or you're under the wheels of a train. I wanted to write about somebody who doesn't get everything she wanted, and is able to look at her life and say it was an interesting one, a worthy one, a dignified one.

"I know that story. I know how you fail in love or you fail at something and you try to make something interesting out of it."

She pauses. "You know, someone recently told me, 'Whenever you write memoir, you're really writing fiction. And whenever you write fiction, you're really writing memoir."

In Frenchtown there is an inn festooned with American flags, a handful of charming restaurants and a pet supply shop into which Rocky barrels forward. (The proprietor gives him a dog treat, greeting him by name.) Nearby is a cavernous shop filled with a rainbow's worth of wooden-bead necklaces; an apothecary chest stuffed with knobs and handles; many bowls of rings, stones and tokens from around the world; and congregations of stone Buddhas like those in Gilbert's front yard. The shop, Two Buttons, is Liz and Jose's. A popcorn machine is dispensing kernels to shoppers, and a clerk pours wine for the grown-ups. Gilbert's found a baby to dangle things in front of, and a friend with whom to gossip.

Behind the store is a leafy path that runs for miles alongside the Delaware River. "You could walk it all the way to Philadelphia if you wanted," Gilbert says, as Rocky pulls her through the mud, his nose attuned to the trail. Gilbert took many fact-finding trips to Pennsylvania with her old friend Margaret Cordi, who helped her tackle the research The Signature of All Things required. Gilbert also traveled to "learn mosses," as Alma says in the novel, enlisting the help of bryologist Robin Wall Kimmerer, PhD, who took her into the woods outside Syracuse, New York, to poke at luxurious carpets of the genus Anomodon, along with the pelts of Rhodobryum roseum that swathe the woods' limestone ledges. Gilbert made lists of what she needed to see in the Tahitian islands -- a verdant cave, a steep hiking trail, a model for the meager oceanside quarters in which Alma would live -- which she visited in 2012. Atop the island of Raivavae, she stood where two weather systems collided, the heavens raining on one side of the mountain and beating down sun on the other. She walked behind a tall, narrow waterfall so divinely beautiful she felt it was sacrilegious for a human being to see.

Now Gilbert comes upon a tree on the river's edge. "This is my second favorite tree in Frenchtown," she says. It's a narrow sycamore, white-trunked and dappled with flaking brown bark. "These trees grow along riverbanks," Gilbert says, "and from above you can spot the path of the river from all the white." A few dozen paces up the path, Gilbert admits how much, during the memoir period, she'd missed inventing characters, building worlds in her mind -- and yet how much those memoirs made this novel possible.

"As a writer," she says, "it's a rare privilege to not be worried about money. It's a rare privilege to have your emotional health. It's a rare privilege in women's history to not have to be a mother if you don't want to be. I couldn't do this kind of book if I hadn't made it through some dark years, or if I hadn't become self-sufficient, or if I had three kids to take care of. I wanted to honor the fact that I'm in this position."

She moves toward another white tree, which possesses a more imposing girth and a broader breadth of branches. "This is my favorite tree in town, because of this business, this whole business right here," she says, pointing to the lavishly mossy filigree on the trunk's northern face. One suspects Alma would love that whole business, too.

"It's been a long time to be away from the only thing I ever really wanted to do," Gilbert says. Then she turns to admire the tree once more, with its great height and oddly beautiful posture -- its torso tending toward the river, its arms reaching for the path.