Wrestlers moan: "ARRRGGGHHH!" The Buddha sighs: "Ahhhhh!" We'll get back to them shortly.

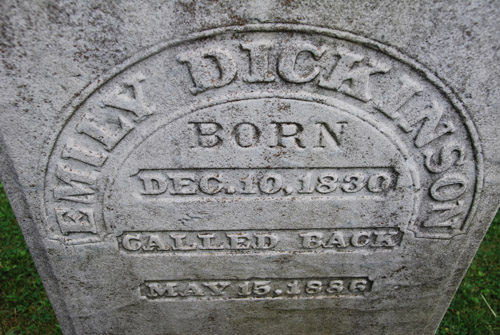

I just spent a week as a turista in New England, visiting the green mountains of Vermont and New Hampshire, as well as the restored home of Emily Dickinson in Amherst, Massachusetts. After almost a lifetime of reading the work of the famously reclusive poet, it was a surreal experience to actually stand in the second-floor bedroom where she wrote and rewrote her devastatingly concise verses on life and death, stashing them away in a dresser drawer, left to be discovered only after her own death in 1886. Even then they remained unread for years, as the publishing project became enmeshed with the neuroses and sex scandals of various surviving relatives and rivals.

When her work finally reached the outside world, it turned out that Dickinson had been busy not only quietly inventing 20th-century poetry in the 19th century, but also -- says I -- tiptoeing toward nirvana. (The same can be said for another visionary virgin, the English Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose work was also published only posthumously. He's got God going on in jazz rhythms way before jazz was invented.)

Of Dickinson's almost 1800 poems, most people encounter only three or four in English class that might appear to endorse a cozy Sunday-school approach to such topics as faith and hope. But Emily was far more tough-minded than that. She eventually stopped attending church, as, for full membership, her local congregation required each member to stand up and testify to having had a conversion experience of Jesus Christ as one's personal savior. One by one, she saw her friends and family members succumb to the peer pressure, even if they had to convince themselves that the conversion had taken place, but the stubborn little redhead held fast. She knew the difference between direct experience and second-hand doctrine.

And her most interesting poems reflect direct experience on the highest level, the level of enlightened reality espoused in Zen, Advaita, Dzogchen, and other such pinnacle teachings of "Eastern" wisdom. For example:

I'm nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

Then there's a pair of us -- don't tell!

They'd banish us, you know.How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog!

This piece is usually taken as a celebration of the poet's deliberately low-profile, nonaspirational way of life, the voluntary shunning of fame -- or perhaps as an expression of sour grapes when fame eluded her. (She did make a few early attempts at publication.) I don't think this interpretation is wrong, but I think the poem (also) is deeper and more literal than that, reflecting what Buddhists call anatta, "not-self," the discovery that the personal self that we usually call "me" has no more substantial existence than the moon reflected on the surface of a lake.

In his quest to solve the problem of human suffering, the Buddha realized that birth leads inevitably to old age, disease, and death. But those events are not suffering's true causes; rather, it is caused by the illusion of a self that is subject to those events. Shit happens, but if there's no you there's no one for it to happen to.

The alleged personal self consists of a bunch of characteristics (physical form, personality quirks, remembered history, etc.), but through quiet contemplation or self-inquiry, relentlessly asking "Who am I? Who or what is experiencing my experiences right now?," we recognize that we cannot be any of those characteristics. We are whatever experiences those characteristics, which must itself have no characteristics or else it would be just one more thing to experience. Slow down, hear that again: We are whatever experiences those characteristics, which must itself have no characteristics or else it would be just one more thing to experience. In other words, we are pure awareness, which may have identified itself with a particular form and name (Emily, Dean, Mohandas Gandhi, Donald Rumsfeld); but we can, in an instant of clarity, see that all such identification is mistaken.

We, of course, are fortunate to live in a time and place where books and teachers, groups and websites dedicated to that enlightening discovery are readily available. Dickinson, it's true, had the advantage of growing up in the wake of the New England Transcendentalists, but evidently she found their work unsatisfying. Emerson, their leader, was a brilliant pioneer but often an insufferable windbag, as tangled up in his own personal doctrines as Dickinson's neighbors were in church doctrines, and just as murky in confusing mere ideas with real experience. And, as the stay-at-home daughter of one of Amherst's most prominent citizens (U.S. congressman, college president), Dickinson found herself sitting at dinner with most of the area's most inflated egos. So the joy of liberation -- the boundlessness of moment-to-moment existence when one discovers that the ego is a flimsy fiction -- must have been especially sharp-flavored for her.

But it was a solitary joy. She was pretty much out there on her own, like the one person awake at a slumber party as everyone else snores away. This poem imagines an encounter with another awakened soul. We can feel Emily peering straight into our eyes (as I've experienced some of my teachers peering into mine), inquiring, "Are you nobody too?" And then quickly she offers the newcomer advice, hard-won wisdom: "Don't tell! / They'd banish us, you know." Be cool. The idea of selfhood is the bedrock of regular people's reality; when you shake it, they feel threatened, and they can respond in unpleasant ways such as institutionalization and crucifixion. Don't cast your pearls before swine.

Then come the frogs. In the second stanza Dickinson draws a droll contrast between the life of liberation and the life of selfhood, of croaking "Me! Me! Me!," with no one to admire (or ignore) you but a bog full of other frogs. Norman Mailer once wrote a book called Advertisements for Myself, and that's the business we're all more or less in. Once we've succumbed to the notion that we're a limited person, an ego, our innate drive toward limitlessness (which is really an intuitive recognition of our true nature) makes limitation intolerable. Then we look around and find ourselves surrounded by other (apparent) egos, also chomping at the bit of limitation. We mistake our fellow sufferers for the problem, and pretty soon we're all playing some form of king of the hill, whether engaged in genteel intellectual jousting on the pages of The New York Review of Books or bashing each other over the head with folding chairs in the arenas of the World Wrestling Federation.

In fact, all the posing and strutting and chest-beating of the WWF gladiators beautifully melodramatizes what the rest of us do in a thousand more subtle, sneaky ways. During last year's presidential election, some folks on the right tried to appeal to their Middle America base by demonizing coastal liberals as "people who think they're better than everyone else." But then it was astutely pointed out that everyone thinks they're better than everyone else. Whether you're a blue-state Perrier sipper or red-state pickup-truck-with-gun-rack guy (sorry for the stereotypes, but I'm making a point here), you think you have it right and the other guys have it wrong, and you want not only to belong to the best group but to be the best in the group. Me, me, me. Man, it's a lot of work.

As Salinger puts it in Franny and Zooey:

I'm just sick of ego, ego, ego. My own and everybody else's. I'm sick of everybody that wants to get somewhere, do something distinguished and all, be somebody interesting. It's disgusting.

It's easy to be sick of other people's egos. That's the basic plotline of every WWF clash. To be sick of your own ego is much more meaningful. It means you're tired of the work of self-advertisement, ready to pack it in. The good news is that you don't have to laboriously chip away at all your egotism (talk about work!) in order to eventually reveal the underlying boundlessness. It's the other way around. Through any kind of effective spiritual practice (for lack of a better term), whether meditation or self-inquiry or devotion or whatever -- or, if you're lucky, just by accident as you're moseying down the street one day -- for a moment you forget to keep your old, well-rehearsed story going. Then the boundless, spacelike, skylike, qualityless quality of pure awareness reveals itself to itself, and the imagined self falls away like a lifeless puppet with laughable puppet problems.

You can make that discovery without a church or a temple or a meditation hall, as Dickinson makes clear in a poem she wrote after dropping out of her local congregation.

Some keep the Sabbath going to church;

I keep it staying at home,

With a bobolink [a type of blackbird] for a chorister [singer in the choir],

And an orchard for a dome.

She also makes it clear that you can make that discovery right now. Don't imagine that some long process stands between you and it.

God preaches, -- a noted clergyman, --

And the sermon is never long;

So instead of getting to heaven at last,

I'm going all along.

When the dream of self dissolves, we awake and see that the true church -- the sacred space, the openness confined by no skull and no horizon -- is wherever we are, with every songbird (and every lawnmower and blaring car radio) spontaneously singing its praise. When we let the raw, unprocessed immediacy of now-reality (a.k.a. God) push aside the longwinded sermonizing of our own little mind, we find, as Jesus says in the Gospel of Thomas, that the kingdom of heaven is inside of us and outside of us, that it's spread upon the earth even if people don't see it. Heaven, nirvana, peace, is not a destination where we finally arrive at the end of a long path; as the Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh puts it, peace is every step.

And we're not only going all along, but, amazingly enough, we've been there all along. There's nowhere else to be.