A few years ago, I staged an emoticon intervention with my father.

I'd realized with horror that he had been sprinkling smiley faces into the messages he sent to his friends, relatives and even business acquaintances, so I sat him down for a stern conversation about the crippling un-coolness that the habit conveyed. No one, I told him, should be caught dead using  . At the time, I congratulated myself on being a caring daughter who'd saved her father from looking like a fool. Yet recently, I've realized my dad was just an early adopter. Emoticons and their more intricate Japanese cousins, emoji, have been enjoying a renaissance, while stickers -- cartoon-like digital illustrations -- are carving out a niche of their own. The growing popularity of all this cutesy communication is usually attributed to the difficulty people have conveying emotion and nuance via quickly-typed text. But emoji and their ilk are more than elaborate punctuation marks, and in fact part of their appeal is precisely their indefinite meaning. They're a way to say something to someone when you don't have anything to say, a digital alter ego that establishes a virtual presence with another person, without any specific purpose besides "hi." Using emoji, in a sense, is like hanging out online. In the past year, frowny faces, clinking beer mugs, adorable chicken legs and other illustrations have become virtually omnipresent online. My Instagram feed frequently has more emoji than photographs: Snapshots are captioned with a sprinkling of emoji, which range from the mundane (heart, kissy lips, crying face) to the poetic (bowl of ramen, power plant, dancing girls in black leotards and cat ears).

. At the time, I congratulated myself on being a caring daughter who'd saved her father from looking like a fool. Yet recently, I've realized my dad was just an early adopter. Emoticons and their more intricate Japanese cousins, emoji, have been enjoying a renaissance, while stickers -- cartoon-like digital illustrations -- are carving out a niche of their own. The growing popularity of all this cutesy communication is usually attributed to the difficulty people have conveying emotion and nuance via quickly-typed text. But emoji and their ilk are more than elaborate punctuation marks, and in fact part of their appeal is precisely their indefinite meaning. They're a way to say something to someone when you don't have anything to say, a digital alter ego that establishes a virtual presence with another person, without any specific purpose besides "hi." Using emoji, in a sense, is like hanging out online. In the past year, frowny faces, clinking beer mugs, adorable chicken legs and other illustrations have become virtually omnipresent online. My Instagram feed frequently has more emoji than photographs: Snapshots are captioned with a sprinkling of emoji, which range from the mundane (heart, kissy lips, crying face) to the poetic (bowl of ramen, power plant, dancing girls in black leotards and cat ears).

Facebook recently launched its own breed of emoticons, a stable of yellow faces depicting feelings of disappointment, annoyance and the feeling "meh" that are based on research done by Darwin. Startups are even touting stickers as a business model: The social networking app Path launched a store that peddles its own, branded stickers, while Lango, a messaging app that sells images users can add to their texts, said hundreds of people had purchased its $99.99 all-inclusive sticker packs within a few weeks of the app's launch. An app created by Snoop Lion, aka Snoop Dogg, sells $30,000 a week worth of digital stickers, according to the Wall Street Journal.

And while my father still isn't the typical emoji and emoticon user, emoji use in Japan spread from teenage girls, their early adopters, through all demographics. Lango notes that its users are currently about 40 percent male, and between 15 and 25 years old on average.

As we continue communicating more consistently, with more people, in more places, than before, we've turned to images as a way to transpose some offline customs, like comfortable silences between friends, into the online realm.

Mimi Ito, a cultural anthropologist researching technology use at the University of California, Irvine, explains that while email and desktop correspondence tends to be focused on completing a set task, a great deal of mobile communication -- given how frequently we have our hands on our phones -- is about sharing an "ambient state of being." People tend to text a great deal with just two to three people they know well, but they simultaneously seek to maintain a "virtual co-presence" with nearly a dozen acquaintances. In these cases, pictures -- vague, but also personalized -- come in handy. A typed message seeks a definite outcome or answer. Emoji are like the smile from a colleague across the room, or the small talk you make walking to get coffee. It's pointless communication that nonetheless puts you in a good mood. "Part of the reason the volume of text messaging is so high because lot of exchange is just, 'This is what I'm doing, this is what I'm feeling,' which is transmitting, 'I'm here with you, I'm connected to you,'" said Ito. "People often like to feel like they're inhabiting the same space as each other... Emoji and emoticons are really good for conveying that kind of thing." As people come to rely on emoji to translate face-to-face habits into the digital sphere, many have picked out a favorite emoji they return to over and over again. For me, it's the monkey cradling its head in its hands. A friend says she's partial to the "cheek guy" -- a smiling yellow face -- while another finds himself returning to the ghost sticking its tongue out. The ambiguity of emoji can also make them frustratingly passive-aggressive, allowing people to send a response that's not a real answer. A friend complained that her boyfriend has adopted a maddening habit of sometimes answering her specific questions with " ." It's an evasion, albeit a friendly one. "You can create a mist of meaning," noted Tyler Schnoebelen, co-founder of Idibon, a startup analyzing language data, and author of a study on the use of emoticons in social media. "People have a sense of where you're at, but it's a little bit obscure because these expressive things don't mean anything particular." Companies pushing stickers in their apps boast that their huge (and growing) selection of images ensure an illustration for every occasion, or a sticker pack for every personality. "If you give people a library of a thousand images that lets them says exactly what they want to say, they're going to gravitate toward those images," noted Jennifer Grenz, vice president of marketing at Lango. Saying exactly what you want to say is, to a large extent, beside the point. Enthusiastic emoji users take pride in showing how much they can do with very little, and part of the appeal is seeing how a limited cast of emoji characters can be repurposed in unexpected ways. Under the hashtag #EmojiArtHistory, the miniature digital figurines have been used to recreate great works of art, such as Grant Wood's "American Gothic" (

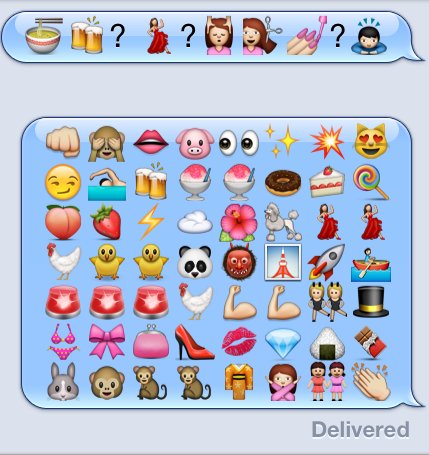

." It's an evasion, albeit a friendly one. "You can create a mist of meaning," noted Tyler Schnoebelen, co-founder of Idibon, a startup analyzing language data, and author of a study on the use of emoticons in social media. "People have a sense of where you're at, but it's a little bit obscure because these expressive things don't mean anything particular." Companies pushing stickers in their apps boast that their huge (and growing) selection of images ensure an illustration for every occasion, or a sticker pack for every personality. "If you give people a library of a thousand images that lets them says exactly what they want to say, they're going to gravitate toward those images," noted Jennifer Grenz, vice president of marketing at Lango. Saying exactly what you want to say is, to a large extent, beside the point. Enthusiastic emoji users take pride in showing how much they can do with very little, and part of the appeal is seeing how a limited cast of emoji characters can be repurposed in unexpected ways. Under the hashtag #EmojiArtHistory, the miniature digital figurines have been used to recreate great works of art, such as Grant Wood's "American Gothic" ( ). The Brooklyn Academy of Music followed up with #EmojiAvantGarde, encouraging followers to translate pieces by artists like like Pina Bausch and John Cage into emoji.

). The Brooklyn Academy of Music followed up with #EmojiAvantGarde, encouraging followers to translate pieces by artists like like Pina Bausch and John Cage into emoji.

"Which emoticons you use says something about you," noted Schnoebelen. "Just as your word choice or accent says something about you."

It's high time there was a German word for the pleasure derived from using a particularly obscure emoji in a particularly clever way. Or maybe you could just say,  .

.

This story appears in Issue 54 of our weekly iPad magazine, Huffington, in the iTunes App store, available Friday, June 21.