In 1994, in his first official State visit to Washington, Nelson Mandela had a simple message for the American people. The newly elected president of South Africa encouraged investment in his country after years of economic sanctions -- sanctions that helped end the apartheid system of racial separation but also crippled South Africa's economy.

President Bill Clinton took note. Standing at Mandela's side on the South Lawn of the White House that day, he announced a new $100 million development fund for southern Africa. Despite the "old and deep wounds of apartheid," Clinton said, "the United States will continue to do everything in our power to support the new nation you and your South African people have created and now seek so strongly to build."

Nearly two decades later, the fund that Presidents Clinton and Mandela launched to provide economic opportunity to the formerly disenfranchised populations of southern Africa

is coming to a close. It's a testament to the success of this noble economic experiment, and the remarkable rebirth of the South African economy, that the fund has now outlived its storied role.

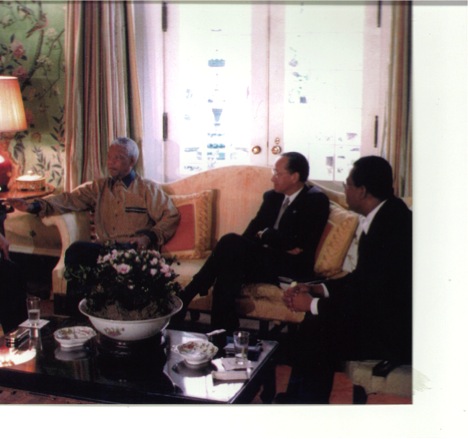

Carlton Masters, far right, with Nelson Mandela, L, and Franklin Sonn, center, the former South African Ambassador to the United States

The Southern Africa Enterprise Development Fund, or SAEDF, was not the first Enterprise Fund that the United States established to kick start the economy of a developing region. Or the largest. But despite long odds, it succeeded. SAEDF provided more than $80 million in financing to indigenous private businesses in southern Africa (the original $100 million pledge later was reduced to $80 million.) It held interests in at least 18 start-up or small companies. It sponsored 12 financial intermediary firms, extending the reach of SAEDF's limited capital by leveraging additional monies to channel to local entrepreneurs. Most importantly, the businesses that SAEDF funded employed over 2,500 individuals directly and created spin-off jobs for thousands more.

Congress established the first Enterprise Funds in the 1980s. Modeled after private equity and venture capital funds, they are funded by U.S. tax dollars and run by independent and unpaid boards with investment and business expertise. Today, these unique Funds have invested in more than 500 companies in eastern Europe and Africa and created more than 250,000 jobs.

From the start, the southern Africa fund was structured differently than its European counterparts, creating some inherent commercial disadvantages. SAEDF was the only Enterprise Fund with a developmental mission, a mandate to fund development projects in remote or troubled regions while also turning a profit. At the request of the U.S. government, for example, it built a hospital outside an impoverished Cape Town township and then gave the hospital to the community. To address the all-white farmland ownership in South Africa, SAEDF loaned $2 million to help establish an employee share trust for indigenous farm workers, to give them an equity stake in a large corporate farm. These worthwhile projects, while assisting long-suffering communities, were of little help to SAEDF's balance sheet. The 10 European Funds, by contrast, had the luxury to focus solely on projects that grew profits.

Carlton Masters, right, with Jakaya Kikwete, current President of Tanzania

Second, SAEDF was the only US Enterprise Fund run by a government bureaucracy. SAEDF from the beginning fell under the control of the State Department's US Agency for International Development. While its European counterparts operated independently like private equity funds, SAEDF was managed directly by USAID administrators with limited experience running private investment companies.

Finally, SAEDF was the only Enterprise Fund that served so many countries -- 11 southern African nations in all -- with one of the smallest budgets. It had to split a smaller pot among a much larger pool of recipients, all the while mastering multiple legal systems, myriad languages and disparate customs in 11 different nations. And, under USAID rules, half of SAEDF's funding had be spent in South Africa. (That requirement continued even after South Africa's economy began to roar back.) That left $40 million for 10 other African nations, or just $4 million per nation if divided equally, which was never the intent of the program.

Candidly, not all our efforts worked. With USAID's full approval and oversight, SAEDF attempted during the 2009-2011 world economic downturn to establish a private equity fund in southern Africa. Many of the European Enterprise Funds, some with funding of up to $350 million in U.S. grant money, had launched private funds in their countries by seeding those funds with proceeds from their liquidations. Supporting the new private equity funds met USAID's development mission in that they allowed the U.S. government to exit the investment efforts in those countries, minimizing risk while passing the torch to the private sector to continue supporting economic development in emerging markets.

But SAEDF's attempt at privatization failed. USAID had agreed that, at U.S. taxpayers' expense, three former SAEDF employees could form a management company that they would own. USAID gave the three partners two years to get irrevocable commitments from private investors of at least $37.5 million. But when they couldn't, USAID shut the venture down and directed SAEDF to sell off its properties.

So that's what SAEDF is doing now. It has listed the sale of a Tanzania hotel for $40 million, is selling off Malawi telecom interests and liquidating other assets. All proceeds will flow back to US taxpayers. The silver lining is that the economy in southern Africa is so much stronger now--thanks in part to SAEDF--that it is time to close up shop.

"SAEDF attracted so many other commercial and governmental investment firms into the region that USAID feels that SAEDF's mission is now complete," said Ambassador Andrew Young, who was the SAEDF Chairman from 1994 to 2011 and is the former US Ambassador to the United Nations. "While all the ills of the apartheid system have not been cured, there are now private equity funds, banks and hedge funds eager to invest in southern Africa, including several headed by managers trained and inspired by SAEDF. We just hope they continue to be responsive to the needs of the people we helped over the years."

In 1994, during President Mandela's historic visit to Washington, he praised President Clinton for "ensuring that Africa does not become a forgotten continent." With SAEDF's assistance over these past two decades, the United States has helped live up to that crucial commitment.

Carlton A. Masters is Chairman of the Southern Africa Enterprise Development Fund.