Imagine if we all had full, unrestricted health care coverage and could select what blood tests, bone scans, heart pills and treatments we want, and decline those we'd prefer not to take.

Some might say, even assume that our already unchecked health care costs would escalate; our demanding, aging population would drive the system to even more exorbitant levels.

But maybe, if doctors would provide only the kinds of care people choose for themselves, the price of medicine would go down.

With so much talk of medical expenses -- attributed to expensive new cancer drugs, innovative procedures, doctors' desire for income, corporate concerns and other interests -- few politicians, policy experts or editorialists are asking about individuals' care preferences. By this I don't mean to suggest there's been insufficient attention to monetary matters like insurance co-payments and COBRA extensions, which are indeed important. What's missing is a solid discussion of the type and extent of treatments people would want if they were sufficiently informed of their medical options and circumstances.

Many patients, a.k.a. medical consumers, would choose less, at least in the way of technology, than their doctors prescribe. And more care.

Not all of us care to die in ICUs, plugged into monitors with breathing tubes in our throats and feeding holes in our stomachs. Rather, the comfort of a hands-on physician, someone who's honest and realistic, who treats what's treatable, who's kind and considerate, is more than many hope for.

I know this based on my experience as a physician who has practiced for nearly 20 years, and as a patient who's had breast cancer and other chronic medical conditions since childhood.

"Please, don't ever let that happen to me" was one of the first things I told my husband after my breast cancer diagnosis some years ago. As a physician, I'd witnessed too many people end their lives in a cloud of treatments, intended to help, but really just prolonging agony.

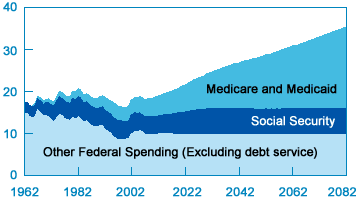

The U.S. spends over 2.4 trillion dollars each year on health care. Medical outlays skyrocket as patients near death; typical life-extending measures include costly procedures, medications, intensive nursing and care by multiple physicians. Medicare, the largest provider to those 65 and older, exhausts roughly a third of its $400 billion budget on end-of-life care.

Last month the journal Cancer published a troubling report revealing that a majority of U.S. doctors would only raise the subject of DNR orders, palliative or end-of-life care with patients who have metastatic cancer and a poor prognosis. The article generated considerable attention in the press for good reason - it bears on health care costs, patients' rights, doctors' communication and time constraints.

The study findings mesh with my own experiences as a practicing oncologist, when I observed that many good physicians are reluctant to stop prescribing chemotherapy and other treatments even as their patients near death. The reasons vary:

Some doctors sincerely think it's better for their patients if they stay upbeat, and this may indeed be true.

Some recognize that if you tell someone there are no curative options left, they'll go elsewhere. Most people, if they're sensible, do want to get well. And many are desperate enough to try anything if a doctor tells them it might work.

Another, unfortunate factor is financial pressure for physicians; giving treatment is far more lucrative than billing for simple office visits.

Doctors have egos, too. If you can "fix" someone thought hopeless, that's great. It's not just the patient, but your reputation at stake.

And feelings -- I've seen physicians become so invested in a case that they don't realize when therapy is useless.

Yet, maybe some dying patients would appreciate a doctor's honesty.

These issues relate directly to the practice of oncology, the area of medicine I know best. But similar hesitations and conflicts of interest arise among doctors in most fields -- cardiologists caring for people with severe heart disease, neurologists caring for people with end-stage Parkinson's, and infectious disease experts caring for people with late-stage HIV, to name a few.

I think that if doctors could somehow find the time, and take the trouble, to talk with their patients in a meaningful way, and then heed their patients' wishes, they might find that many people would, of their own volition, put a brake on health care spending.

For this reason, among the changes in health care I most favor is greater support for primary care and non-procedural services. If doctors were paid more for thinking and communicating, rather than ordering tests and performing treatments in a perfunctory manner, they and their patients might opt for less expensive, more humane remedies.

From the patients' perspective -- if we could just let our physicians know about our preferences, and make sure they listen and take note, we'd be getting the care we want, no more and no less.