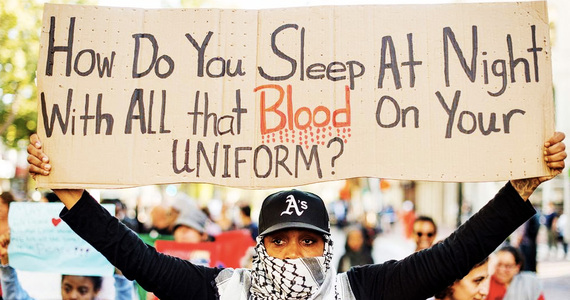

"You can truly grieve for every officer who's been lost in the line of duty in this country, and still be troubled by cases of overreach. Those two ideas are not mutually exclusive. You can have great regard for law enforcement and still want them to be held to high standards."

-Jon Stewart The Daily Show

Nearly thirty years to the day "NBC took a huge gamble ... [putting] a strong, loving and successful Black family on prime-time television," ABC rolled the dice in similar fashion by launching a series chronicling a black family's quest to "establish a sense of cultural identity ... that honors their past while embracing the future." With The Cosby Show, NBC landed an iconic television series that firmly reinforced "the widely held virtues of the nuclear family," and radically altered the portrayal of blacks on the small screen, by offering a "30-minute refuge from some of the negative imagery found on television." ABC's `Black•ish seeks to continue this legacy by depicting an innocuous, yet nuanced portrayal of the black family that seeks to illustrate a multi-dimensional portrayal of blackness. Nevertheless, while The Cosby Show shied away from tackling some of the more provocative issues of its day: the crack-cocaine epidemic, AIDS, and escalating homicide rates within the black community; `Black•ish has elected to approach some of the pressing issues of its day directly. In this regard, `Black•ish's deviation from its predecessor become quite clear with its latest episode.

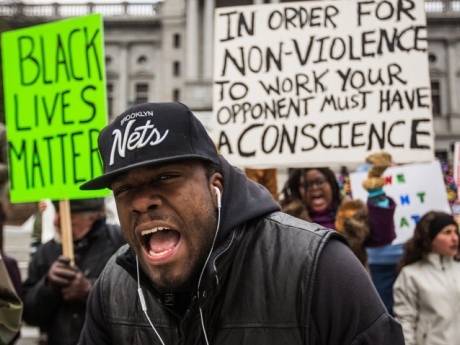

`Black•ish's latest episode, entitled Hope, explored the Johnson's varied reactions to reports that a local grand jury failed to indict a police officer implicated in the death of an unarmed black man. The Johnson children asked their parents and grandparents difficult questions many black children have asked their families throughout the years. Namely, how could justice seem to elude the family of the young man killed by police when the issue of the officer's culpability never seemed in question? How could the grand jury fail to see what seemed so clear to them? Johnson family patriarch, Andre "'Dre" Johnson, taught his children that their encounters with law enforcement had a greater likelihood to become deadly; his wife Rainbow desired to engender a sense of faith in the judicial process and respect for the authority of police officers. In one scene, sure to live in television lore, Mr. Johnson reminded his dear wife of how quickly their hopes in a just system could be dashed. That conversation, along with the other conversations the Johnsons had with their children and conversations the Johnsons had with 'Dre's parents, displayed the complex, inter-generational dialog black families across America have had for decades. These conversations eventually espouses the painful premise many know to be true; black people disproportionately experience unfavorable encounters with law enforcement. Black families across America no longer have to rely on anecdotes, hashtag memorials, and episodes of sitcoms--their suspicions have been counted and documented.

According to a study published by The Guardian, 1,140 people in the United States died at the hands of law enforcement in 2015 (41 of whom died in police custody). Suffice to say, police killings in the US have reached epidemic proportions, especially when compared to the number of police killings in other countries. The Guardian began the "grim task" of recording the number of people killed by American police officers because the United States government fails to do so. In essence, the nation's top-data experts in Washington determined they could not accurately count the number of Americans killed by police each year (in large part because major police departments, like the NYPD, failed to report), so they stopped. In October of last year, FBI Director James Comey appeared before 100 politicians and law enforcement officials, and expressed frustration regarding the federal government's "ridiculous" and "embarrassing" failure to precisely document the number of people killed by police officers each year. The Guardian's study, entitled The Counted, then exists as one of few metrics chronicling the mounting deaths of those killed by police officers in the US each year.

In many ways, The Counted confirms what black people have anecdotally attested to for decades--the American criminal justice system harbors stark, systematic, racial discrimination, and the epidemic of police brutality is merely one component of it. Without question, scores of men and women perform their jobs in law enforcement admirably, routinely risking their lives for people they may never meet again; yet those brave men and women's honorable service does not nullify the existence of systematic injustices exhibited through police brutality. With regard to police killings, The Counted discovered blacks are twice as likely as whites to be unarmed when killed during encounters with law enforcement, and black men are nine times more likely to be killed by police than white men. Other reports have found police officers use less force on suspects who appear white, regardless of the crime the suspect has allegedly committed.

Many endeavor to explain these racial disparities in those killed by police officers by espousing theories of black criminality acting as a pervasive pathogen plaguing the black community. These explanations often rely on faulty logic referencing "black on black crime" as the more pressing concern for the black community. Notwithstanding, the phrase "black on black crime" is a racialized colloquialism used as a red herring to distract from legitimate critiques of institutional oppression. The bulk of crimes in America amount to crimes of proximity, thus people commit crimes against those who live near them. America is segregated, so most Americans who commit crimes do so against people who look like them. Consequently, the national discourse on criminality does not use clumsy phrases like "white on white crime," "brown on brown," et cetera. Those phenomena are termed what they are--crime. Nevertheless, when people raise their voices against state-sanctioned violence as it manifests through police brutality, particularly as it disproportionately impacts the black community, the rhetoric trumpeted reverberates the familiar refrain--"black on black crime" is the only germane issue.

US crime statistics sing a different tune, and thereby document a relatively similar rate of crime between whites and blacks. The disproportionate number of arrests and convictions of blacks is readily explained by racial bias in the criminal justice system at every fundamental level. For example, blacks are twice as likely to be arrested during encounters with law enforcement; black offenders receive sentences 10% longer than white offenders convicted of committing the same crime; when controlling for severity of crime, prior criminal history, and other relevant factors, white men between the ages of 18-29 are 38% less likely to be imprisoned as their black counterparts. In light of such galling racial disparities in how the American criminal justice system doles out its sanctions, one could begin to comprehend The Counted's findings that "one in every 65 deaths of a young African American man in the US is a killing by police." This data simply comports with centuries of racialized laws and racialized law enforcement. Consequently, `Black•ish's latest episode chronicling a black family's examination of how police brutality impacts their community serves as yet another illustration of how art imitates life, often in harrowing ways.