The exposure of Rachel Dolezal, a white woman passing for black, was just a blip in a year of more urgent stories about race in the United States. Indeed, many expressed annoyance that the story was given so much play, in light of more serious injustices. But the interest in Dolezal's story was not just crass sensationalism. The issues it raises should concern anyone who has tried to understand what exactly constitutes "race" in the United States and, more specifically, whether one can escape or overcome the race one was born into.

The question asked over and over about Dolezal's deception was: Why would anyone want to be black??? Why would someone give up the privileges of being white in America and willingly embrace the disadvantages that come with being black? People asked this as if it were truly perplexing, but why on earth would anyone want to be identified with a race that practiced a brutal form of slavery for over two hundred years, then set up a system of segregation and discrimination bolstered by white terrorism and an ideology of white supremacy, the effects of which still linger today despite legislative attempts to overcome them? Who wants that as their "racial heritage?" Who wouldn't give up their privilege if they could escape that burden?

Even without the burden of a racist history, whiteness is nothing to brag about. Culturally, it is associated with suffocating conformity and bland banality, the vapidness of suburbia and the joylessness of people who can't dance. Norman Mailer famously linked whiteness to gas chambers, "radioactive cities," and rampant militarism in his 1957 essay, "The White Negro." In The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin saw whiteness in America as "sterility and decay," asking why he, or any black person, would want to "be integrated into a burning house." Whites might have material privilege but they are spiritually and morally impoverished.

As a recent essay by historian Nell Irvin Painter pointed out, there is no good way to be white in America. Either one can buy into the trappings of a very race-conscious whiteness, ala the KKK and Dylann Roof, or one can consider one's whiteness insignificant and proclaim that "race doesn't matter," which for many of my colleagues in academia amounts to denying the experiences of people of color and the ongoing existence of racial inequality. A third option is to confess one's white privilege, acknowledge the existence of racism and the ways in which race does matter, and try to comply with the new rules of diversity. None of these options, however, was quite right for Rachel Dolezal.

Instead Dolezal attempted to escape the burden of whiteness by becoming black and participating in the struggle for racial justice. I have no desire to condone or defend Dolezal's masquerade. But I am interested in the historical precedents of this sort of "reverse passing." Whites passing as black has been, historically, rarer than blacks passing as white, but it did happen (see Susan Gubar's book Racechanges: White Skin, Black Face in American Culture, and Laura Browder, Slippery Characters: Ethnic Impersonators and American Identities), and just as importantly, it was imagined.

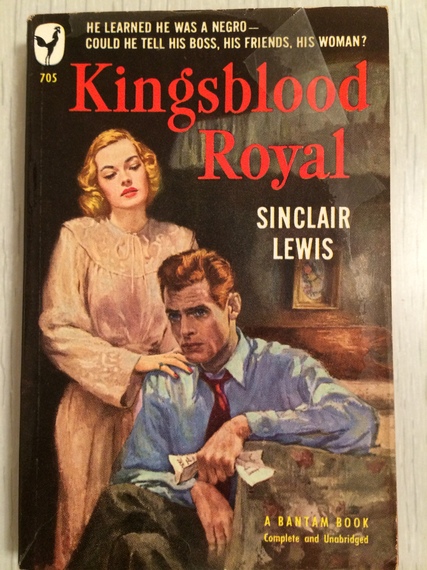

In fact, in 1947 a best-selling novel by the once-renowned author Sinclair Lewis seems to foresee the story of Rachel Dolezal. Kingsblood Royal was about a white banker from Grand Republic, Minnesota who overcomes his middle-class, milquetoast destiny by "resigning from the white race," becoming black, and joining the fight against racism. The protagonist is Neil Kingsblood, a regular, well-intentioned white man who knows racism to be wrong but is unaware of the various ways he is in fact racist. While researching his family genealogy, he discovers he is 1/32 black, which, the novel intones, means that in some states (although not the one he is living in), he would be considered black. After months of anguishing about what to do with this information, he "comes out" as a black man, in part because he has gotten to know the black community. He has met people who are "just like him," yet somehow more dignified. Their suffering has given them depth, conviction, and meaning, all things that he as a privileged white man lacks. He wants to be part of their world, a world that transcends the petty soullessness of bank ledgers and country clubs. Although the novel indulges in worn stereotypes of blacks as long-suffering paragons of virtue, restraint, and wisdom, it also does a surprisingly thorough job of cataloging all the privileges Kingsblood's whiteness affords him, including his job, his home, his ability to live in a desirable neighborhood, his social standing, his credit, his wife and daughter's virtue, and finally his own safety and well-being, all of which he loses by becoming black. But he doesn't for a moment regret it. The loss of his privilege is his salvation; it redeems his humanity. The final scene foreshadows the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, as Vestal, Kingsblood's very white, symbolically-named wife, joins their new black comrades in battling the white mob, proclaiming, "Didn't you know, I'm a Negro, too."

One can't help but think that some version of this story was at work in Rachel Dolezal's fantasy.