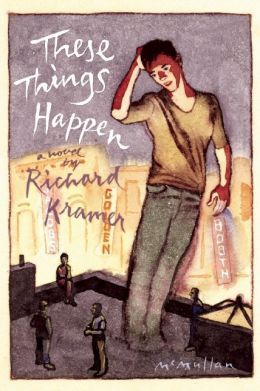

No less than legendary gay writer Armistead Maupin suggested that I read These Things Happen by Richard Kramer. When Mr. Maupin suggests, you read. I was quite simply blown away. First time novelist Richard Kramer is an Emmy and Peabody winning writer, whose resume includes such legendary TV programming as Thirtysomething, My So-Called Life, Tales of the City and Once and Again. His first story appeared in The New Yorker when he was still an undergraduate at Yale. I wondered what took him so long to write this wonderful book. If you're looking for a great summer read, well you've found it, herein I talked to Mr. Kramer.

What was the genesis of this story?

THESE THINGS HAPPEN simmered on the stove for about twenty-five years. As time passed, more and more bits and pieces got thrown in, and what emerged was -- something that surprised me, and something I never expected.

George, who's the book's main character -- a former chorus boy turned restaurateur, living with his long term-partner in New York's theater district, sudden host to his partner's fifteen-year-old son -- can be traced both to an actual person and, even more, to a realization I had about him. During the four years when I was writing, producing, and directing Thirtysomething I would go to the same restaurant every night for dinner and unwind, doing the next day's work, grateful for the silence after a day's endless chatter. The restaurant, gone now (in LA, though not in New York) was called Orso. There was a man named Robert who greeted you, who took care of you, who saw to it that in his world everything would be easy, and sweet. And he took wonderful care of me.

He'd lead me to "my" table, in the back, and bring me "my" supper, which was always spaghetti with olive oil and garlic and an arugula salad with shaved parmesan cheese. He was nice-looking without being handsome, especially, gay enough so you could feel comfortable with him and not worry he'd be over-familiar, and you knew he had many secrets about other diners and would never, ever spill them.

One day, after about four years of this, I realized after I'd called the restaurant to tell him that, indeed, I'd be coming that night -- well, I realized that I didn't know his name. I'd never bothered to learn it. Why would I have? He was there to make me comfortable. Why should he have a name, much less a story and a self that was unique to him?

This shocked me, I'm happy to say. I saw, as I've seen many times, how easy, how convenient it is to make someone invisible. I had felt invisible, myself, often, and had made myself invisible, too. So that started years of wondering about that, and when I had the first glimpses of the novel I knew I somehow wanted to write about an Invisible Man in a visible setting, someone with a perfect blazer, a rep tie, nice hair, and no name. Who worked in a restaurant. Who nurtured you, and didn't look to you to return the favor. Who might this guy be when he went home, I wondered? Who did he love, who was he loved by, what did he care about? I wrote Robert a note (this was before email!), told him what I'd realized, and arranged to take him out for coffee, years before people went out for coffee. We talked, and I asked him about his life, and of course it was specific, and vivid, and rich, all the things a novelist wants for a character. And I used none of it. But I certainly used him, or my idea of him.

You worked on some groundbreaking TV, how did you get your start?

One thing about groundbreaking TV -- you never know that's what it is at the time. In fact, what you mostly think is "Please don't fire me." Today everyone gets fired, all the time; no one is safe. We were a little safer, just a little, and no one fucked around with us, which isn't a prescription for ground-breaking TV, but doesn't hurt. And for me, TV was an accident. I wanted to be Alvin Sargent, or Arthur Laurents. TV was a "comedown", and it's what saved me, and gave me a career from which I could learn something; there's nothing you learn less from than "development"; being "in development" is like going out to dinner with a dead person who took his own life and can't find anyone to haunt. It's pathetic. All I ever learned from development is what morons those who have development jobs are -- and I mean every single one I ever worked with, with the exception of Ed Zwick and Marshall Herskovitz, who weren't development people, of course, but producers, and writers, themselves, and who knew just how to get a writer to access those parts of himself that were specific and authentic. I had been writing in Hollywood for ten years before thirtysomething came along, and if it hadn't I think it's likely I'd have never learned anything, and would have looked for a more "solid" career.

But my actual start was when I sold a short story to the New Yorker when I was a senior at Yale, and thought it was the greatest thing that had ever happened, until forty years later I realized it wasn't. I feel lucky to have lived long enough to see that. After that, I wrote a spec script for a show called Family that, somehow, they bought. They brought me to LA, to watch its shooting (that would never happen now). Within a week of moving here I met Ed and Marshall. We became close friends. I wrote a series of movies for television that did get made, and a series of movies that didn't. Then in 1987 Ed asked me, after the Thirtysomething pilot had been picked up, if I'd like to come work with them on this show that they hoped was terrible so it would get cancelled quickly. I deigned to say yes, with no clue that within about two days I would see that these two agreeable schleppers who were fun to get stoned with were, in fact, geniuses and would, if I didn't screw it up, change my life.

What character in These Things Happen is the closest to you?

Oh, my God. All of them, I guess. Which isn't an answer. If I had to pin it down, I have to say I'm Wesley, the kid, and George, his dad's partner. I like all the characters equally, even the "bad" ones, or one in this case, and I'm not about to spoil a big turning point in my own book by saying who that is, or what that person does. But I will say that the fun of writing the book, of being able to go into the assorted minds of a group of what I hope are interesting people, was that I could see everyone's "side", I suppose, and convey a sense of them beyond the actions they take; in other words, I could create a public-private experience of each person, something that is hard to do in drama. There's a phrase from Noel Coward that has always stayed with me, about people, "deep down in their private lives ..." That's where I wanted to go in this book, and the challenge of it was to do so with a group of pretty public people. I think there's something fundamentally gay in that. What? I'm not sure. But there's something. And I believe it found its way into These Things Happen.