Climate change. I've decided to take a stand on this one issue, a principled stand. Principle is one thing, at least, that can never be taken away from someone unless it is willingly given away. It may not make you popular, though, because a voice raised in passion in polite society can be a real turn off. I've been asked, time and again, why don't you show climate change in a more positive light? "People" will be put off by the negative. It will be depressing, they tell me.

I show what I have seen, I say, in the magnitude and proportion I have seen it. It is what it is. The magnitude of the problem needs to seen, without filters, for the true challenge to be understood. Solutions and change, that is real change, come only with a collective sense of urgency. The collective coverage of climate change I have been seeing suggests that there are problems "out there" but binge-watching sitcoms on Netflix will help you to forget.

Liam Gallagher of Oasis once sang, "Some might say, that they don't believe in Heaven, go and tell it to the man who lives in Hell." Don't believe in climate change? Go tell it to the good, decent families, I've met whose paradise has been turned into a living hell. Go and see it, or view non-fiction photography (no fudged facts, no self-censorship), if you are unable to get away. At the end of the day, all that matters to my mind is delivering the truth and not simply blowing smoke.

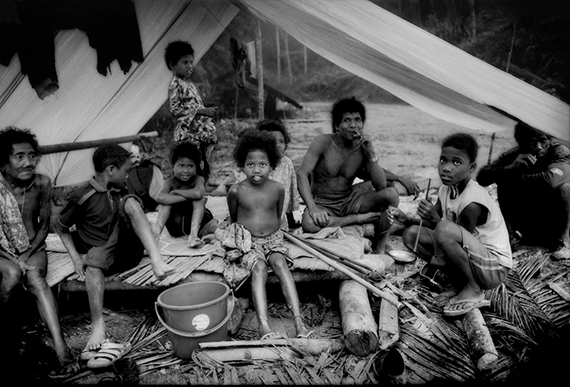

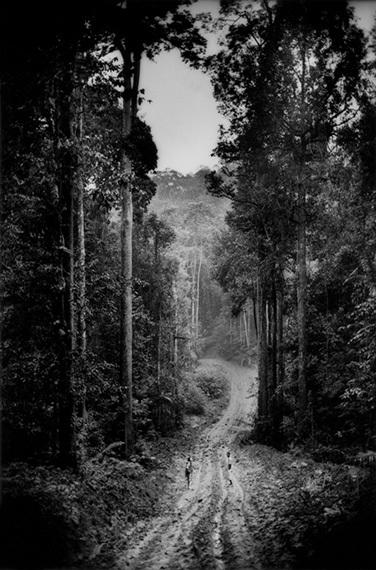

I found some photos online yesterday that had me seeing red. They were snapshots, made in February 2015, of a clan of Batek Negritos hunter/gatherers I had documented in 2010 and 2011 in and around their Malaysian government-funded resettlement camp (out of the rainforest). They showed the aftermath of a massive flood, the kind of flood very rare inside a healthy rainforest, but they no longer live inside a healthy rainforest despite there being a massive one a stone's throw away which also used to be a part of their ancestral homeland. It is Taman Negara National Park in Peninsular Malaysia (pictured below), 434,300 hectares (4,343 sq. km) of protected, 130 million year old primary rainforest that supports tigers, sumatran rhinoceros, Asian elephants, Malaysian gaur (wild bovine), tapir, gibbons, monkeys, over 300 species of birds, over 1,000 species of butterfly and over 14,500 species of flowering plants and trees. The Malaysian government resettled the Batek to the edge of the national park, while forbidding them from hunting or gathering inside the park, part of their ancestral homeland for at least 10,000 years. Logging/oil palm conglomerates arrived nearly 40 years ago and began logging the vast unprotected rainforests (also part of the Batek ancestral homeland) north of the park.

Without consultation with or the permission from the Batek (seen above), these corporations began to cut down those unprotected forests, selling the timber to fund conversion of the forest into vast oil palm plantations. By the time I arrived in 2010, the Batek community had been split in two, with half living in the aforementioned government settlement at the northern entrance to the national park and the other half living about 40 minutes walk up a logging road in a settlement on the edge of the forest. Some Batek, at the government settlement, actually owned cars and motorbikes that they bought by working in the cash economy. The others lived traditionally, off the grid. All Batek were forbidden, by law, from entering the oil palm plantations. So the Batek, found themselves, within less than a half century, sandwiched between two restricted areas that used to comprise their core territory for 10 millennia.

(Above) Batek women take a break in forest surveyed (now clear-cut) for logging in preparation to become the new oil palm plantation.

If that was not bad enough, I noticed in the background of the snaps that the last tiny, tiny sliver of unprotected forest outside the national park boundary had now also been clear-cut, ignoring the need for a buffer zone between the park and the ocean of existing oil palm plantations, just like this one (below) also on the Batek's ancestral land. There had been so little of the Batek's forest left but now even it was gone, and the now-barren hills had been terraced to prepare for a new oil palm plantation. The river that the Batek had relied upon for fish and protein, which ran clear in 2010/2011, is now completely burdened with silt.

The truth is, similar daylight robbery of indigenous land and human rights is happening all over the planet. The Huaorani, the Shuar, the Sa'amaka & N'dyuka Maroons, and dozens of other Amazon Basin peoples; various so-called pygmy people, such as the Bagyeli of the Congo Rainforest; the Penan, Iban, Kenyah, Kayan, the Kelabit to name a few of the Borneo Dayak peoples; the Agta, the Aeta, the Batek, the Dumagat and other Negrito peoples have all experienced either land grabs, contamination of water, degradation of soil or unsanctioned resource exploitation on their ancestral land; or all of the above. They are just some of a sampling of indigenous peoples that I have personally documented. Indigenous peoples, particularly those living in fragile arctic and tropical eco-systems, are the canaries in the human coal mine, forecasting troubles to come for all of us.

So, I've taken this stand.

********************************************************************************

No, I do not believe that humans will die out entirely from climate change, but many endangered species will. I do believe, however, that many people will needlessly suffer grinding poverty as a result of global warming, and many will also die as a direct result of that poverty.

As a child, I lived from the age of 7 until 19 in the New York City area. In 1967, when I moved there from California, waterways near massive oil refineries on the New York - New Jersey border would sometimes actually catch fire when petroleum barges would spill toxic crude oil and it would float on the water's surface.

By the late '70's, because of new environmental-protection laws, cattle egrets and other water birds had begun to return. In the suburbs where I lived, just 20 miles (30 km) from Manhattan, first raccoons and opossums began to filter back. By the late '90's, I would go jogging, on family visits back, and see deer in town parks. In fact, a couple of years ago, while staying at a friend's house in Bushwick, Brooklyn, two rowdy raccoons crossed my path near a cemetery during a jog. I have been told that even coyote and deer have been sighted within the New York City limits. Change is possible.

If that massive change is possible in New York, reducing greenhouse gases is also possible over time. If wildlife are healthy, the environment is healthy. If the environment is healthy, people can live healthier lives. Simple stuff.

For me, making a stand, or raising one's voice is not bad form. It is not a turn off. I believe it is necessary. The post-industrial north has made great progress in cleaning up a dirty past but it can mislead us, in the north, into thinking the whole world has followed suit. The truth is that the heavily polluting industries have simply been exported to developing countries, for their cheap labor and lax environmental protection laws, while our hunger for resources, if anything, has only grown. Don't believe in climate change? Go tell it to the Batek who is now living in a terrestrial hell, so that our shampoo is cheaper and our cookies/biscuits are nice and soft.

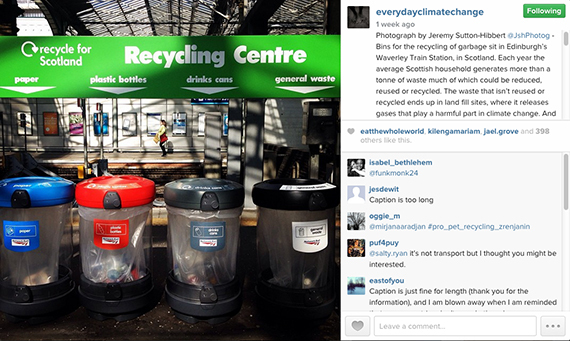

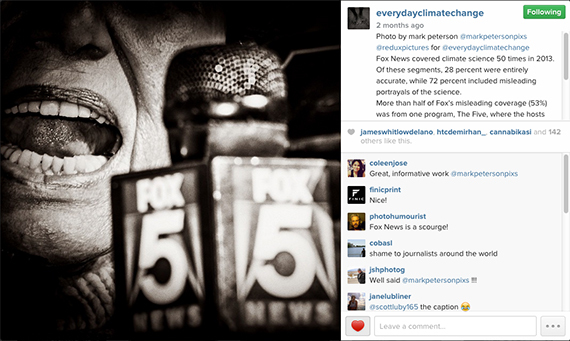

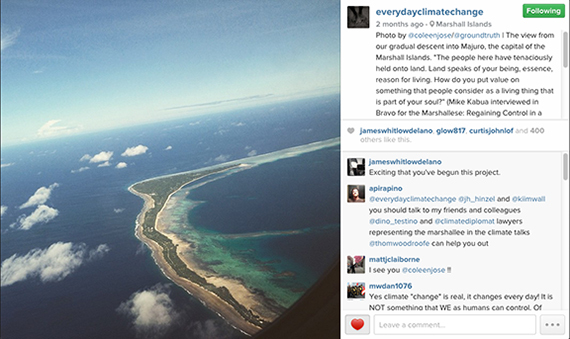

Now, enough about my own work, and experiences. I want to introduce the work of EverydayClimateChange (@everydayclimatechange) Instagram feed photographers who have come together to collect visual evidence. Please check out this little sampling of ECC photographers' important work: