Two years ago on Thanksgiving, not long after I had moved here from London, I was driving through LA with my partner's sister after picking up a few forgotten items from the grocery store.

Stopped at a traffic light I noticed a large crowd of people camped out along the road. My heart ached. "How unfair life is," I said to Juliana. "Here we are on our way home to be with family and friends, and these people don't even have a roof over their head." She looked at me and laughed and I realized that this was one of those "foreign" moments I often find myself in. These people didn't need soup. Black Friday was a mere 15 hours away, and so was that new flatscreen TV.

Since then I have seen how, in my own life and the lives of those around me, the worship of self and stuff continues to hold its position as the cornerstone of American culture. In response to this, I found myself wanting to explore people's reaction to the impermanence inherent in both of these.

Last August, I traveled to the Northern California coast to participate in Project's 387's inaugural artist residency. Project 387 had accepted my proposal to create a series of chalk pastel portraits in the forest as a means to study human attachment and its effects on our wellbeing. Inspired by Japanese philosophy, the portraits were to be left to decay in the forest and provide viewers with a mile-long walking meditation on the transience all things.

Jose, 3 months later

Heavily influenced by Zen Buddhism, Japanese aesthetics are grounded in a commitment to facing things as they really are -- not as we want them to be. In stark contrast to our Western ideals of beauty, Japan holds imperfection, asymmetry and, perhaps most important of all, impermanence as the highest aesthetic values. The ancient Japanese term "mono no aware" refers to the powerful emotional experience felt in response to fleeting beauty. It is precisely the transience of the cherry blossom that elevated its status to the country's national flower.

During my two week stay on the 150 acre property, I spent more than a hundred hours meticulously depicting local faces on tree stumps and logs deep in the forest. I interviewed and photographed six people for the project: the residency's director, her parents (who were the owners of the property), a local man who had worked on the land for more than 15 years, a Mexican immigrant who had maintained and repaired the property for more than 10 years, and a community nurse practitioner to whom the family had offered residence. Each individual shared their story with me and told me how their lives had taken them to this remote patch of land on the Californian coast.

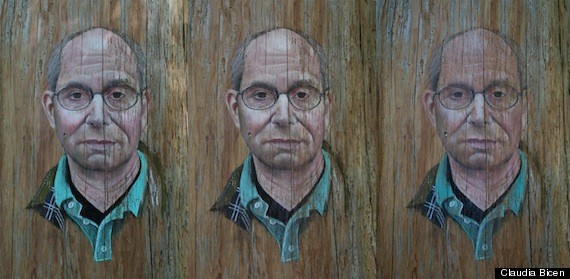

Syd, 2 and 3 months later

On the last day of Project 387, the doors were opened to the public and many people walked through the forest to find the hidden faces. I talked with them about the philosophy underlying the work and received many enthusiastic, nodding heads.

The conversations, however, quickly turned to advice on how to protect the pieces for the future. "Spray them in a protective sealant!" "Cover them in plastic sheeting!" "Cut them out of the land and mount them on the wall!"

After I left the residency, the pursuit of preservation persisted. The property's owners covered all the work in plastic and even gave one piece away to the portrait's subject. I found myself indignant, feeling that my desire for impermanence had been ignored. And there it was, that feeling that the project had aimed to suppress: attachment.

Jose's hand, 2 and 3 months later

I felt I had the right to control the process because I created it; the landowners felt they had the right to preserve the art because it was on their land; the portrait subject felt he had the right to keep it because it was of his face. That's a whole lot of attachment to emerge from a study on letting go.

Over the past few months, I've questioned why the project evolved in the way that it did and why it was so important for all of us to preserve some part of it. Syd, the landowner, wanted to be able to share the portraits with her friends and family. Bobby felt privileged to be the subject of a painting and wanted to keep it. And me? I had found refuge in the delusional belief that I could control the world around me.

Maureen, 3 months later

When confronted with impermanence -- in ownership, in an object, or even in an ideal -- we were all desperate to hold on tight. The cultural microcosm that evolved on this remote piece of land highlighted to me the compulsion with which we overlay myths of permanence on the ephemeral world in which we find ourselves. Both necessary and functional, these myths help us construct a sense identity and self.

Perhaps, then, it is because we have no other choice that we spend our lives building castles in the sand as the water laps our toes.

Allyson

Ray, 2 and 3 months later

Bobby

Bobby's shirt

Bobby, 2 months later