In 2012, I wrote an article for the Sunday New York Times that exposed the use of physical restraints and seclusion rooms with kids in schools across the country.

I learned about these practices, which at the time seemed almost unimaginable to me and many other parents, when I discovered that our 5 year-old daughter had been locked almost daily, over a three-month period, in a seclusion room, which had previously been a teacher's phone booth, and was later used as a mop closet, in the basement stairwell at her school in Lexington, MA.

In the two years since my Times story, the controversy surrounding the use of physical restraints and seclusion rooms in schools has exploded and resonated across the country from Hawaii to Massachusetts, fueled by a powerful combination of concerned parents and enterprising journalists intent on exposing these practices when and where they occur. Meanwhile, many schools have publicly denied their existence, in some cases despite incontrovertible evidence, and parents can find themselves being intimidated or even publicly attacked for speaking out.

For two years, I've witnessed the evolution of this story as a journalist, and at the same time the issue has affected me as a parent whose child was subjected to these damaging practices. As increasing numbers of parents are becoming concerned about the use of restraints and seclusion rooms in schools attended by their kids, and as a national mobilization of concerned parents and others is underway seeking to pass national legislation to curtail these practices, it seemed like a good time to take a look at the issue from a parent's perspective.

Specifically, how widespread are the use of restraints and seclusion? Are they needed? What do parents face when they challenge their schools or speak out about their use? And how can parents and other concerned members of the public get involved with national efforts to insure that all kids are kept safe in school?

What exactly is restraint and seclusion in schools? Is it like a student getting a "time out?"

According to the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce, which is working to ban these practices:

"Seclusion means involuntarily isolating a student in an area by himself or herself [from which the student is physically prevented from leaving.] . . . This includes putting children in dark, small rooms as punishment." This is different than a "time out" in which a student is separated from others to allow him or her a chance to calm down.

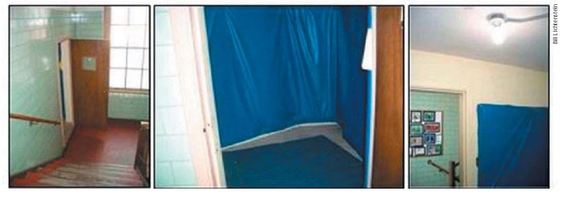

DANGEROUS PRACTICES--The use of restraints and seclusion rooms, such as these in a Lexington, MA school, often lead to physical and emotional injury to students.

Restraint according to the Committee means "restricting a student's freedom of movement [including immobilizing a student's torso, arms, legs or head]. Restraint can become fatal when it prevents a child's ability to breathe. In some of the cases examined in [a 2009 Government Accountability Office] report, ropes, duct tape, chairs with straps and bungee cords were used to restrain or isolate young children."

How widespread are these practices and what kids are involved?

A 2009 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that 20 students had died while in seclusion rooms; countless others as young as three and four years old have been injured and traumatized. One young teen in Georgia hung himself in a seclusion room while staff sat outside the locked door; a seven year-old died face down in physical restraint; and a young teen was suffocated face down in restraint by his teacher twice his size.

According to the advocacy group TASH, recent reports indicate that the shoes of an 8 year-old with Down Syndrome were duct-taped so tightly that she could not walk and her ankles were bruised; a 10 year-old with autism was pinned face down after getting upset over a puzzle; and a child with Cerebral Palsy severed her finger when she was confined in seclusion. Parents often are not told by schools about restraint or seclusion, or they learn about it long after it has occurred.

Federal data released in March from the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights documents the extent of restraint and seclusion, finding more than 267,000 incidents reported nationwide in the 2012 school year alone. According to a recent statement from Rep. George Miller of the House Education and Workforce Committee, "while that number is alarming in itself, what's even more concerning is the fact that many of our largest school districts failed to report on their use of seclusion and restraint at all --indicating that the actual rate of use is likely much higher."

Also alarming, according to Miller, is that "despite the fact that special needs students comprise only 12 percent of the total student population, this data shows that nearly 60 percent of all incidents of seclusion or involuntary confinement involve students with physical, emotional, or intellectual disabilities, and that these students make up 75 percent of those subjected to restraints."

Additionally, their use is disproportionate by race: African-American students comprise only 19 percent of all students with disabilities, but they make up 36 percent of students with disabilities subjected to mechanical restraint.

The Department of Education Office for Civil Rights tracked the use of restraints and seclusion state by state and school district by school district and found: "in Nevada, Florida, and Wyoming, students with disabilities . . . represent less than 15% of students enrolled in the state, but more than 90% of the students who were physically restrained in the state. Nevada (96%), Florida (95%), and Wyoming (93%) reported the highest percentages of physically retrained students with disabilities. . ."

But aren't restraint and seclusion sometimes needed? How else can schools handle kids, especially those who can be difficult and get out of control?

The short answer is, as experts will tell you, that physical restraints and seclusion rooms don't work as ways of helping students learn and practice self-control, and that according to research there are behavioral techniques of working with kids that do work, as well as teaching kids self-regulation, how to negotiate and how to communicate more effectively.

The U.S. Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan, wrote to schools nationally in 2012 saying, "there continues to be no evidence that using restraint or seclusion is effective in reducing the occurrence of the problem behaviors that frequently precipitate the use of such techniques." Furthermore, Duncan stressed that "any behavioral intervention must be consistent with the child's rights to be treated with dignity and to be free from abuse."

According to TASH, there are "evidence-based positive behavioral interventions and supports [that have been] shown to greatly diminish and even eliminate the need to use restraint and seclusion." As an example, Dr. Michael George, director of Lehigh University's Centennial School, an alternative school in Pennsylvania that targets students with aggressive behavioral issues, told the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions that when he arrived at the school, "the use of physical restraint was commonplace." George said he closed the school's two seclusion rooms, and cut restraint and seclusion use from over 1,000 occurrences per year to less than ten through the use of positive intervention plans. "We have the technical knowledge necessary . . . to end the overreliance of seclusion and physical restraint," he said.

Joe Ryan seconds Dr. George. Dr. Ryan is a Professor of Special Education at Clemson University and a national expert on working with students with emotional and behavioral disorders. "It simply defies logic," said Ryan, "that with the current emphasis on implementing evidence-based practices in classrooms, many schools have elected to embrace seclusion and restraint while ignoring safer research based practices for managing aggressive behaviors."

The impact on parents who find their children have been subjected to restraints and seclusion can be devastating.

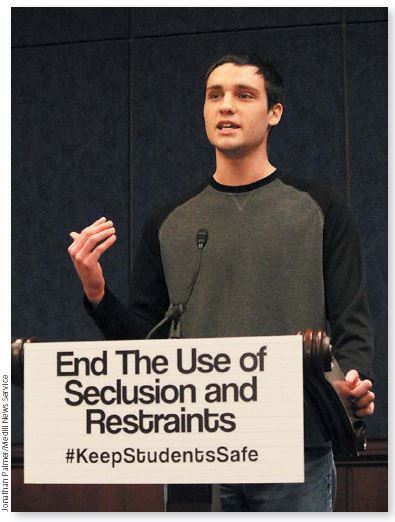

Robert Ernst was subjected to a seclusion room as a first grader in Lexington, MA. Robert, who's now 19, told his story recently in Washington, DC, at an event held for the introduction of federal legislation that would curb these practices.

"I was in first grade and I was taken by my special education teachers to a seclusion room for acting out in class," said Robert. "I was dragged down the hallway of the school by my wrists, and thrown into a windowless, padded concrete room by myself, complexly unsupervised for up to a half hour at a time . . . At the time this was extremely terrifying."

His mother, Wendy Ernst, recalls what it was like to try and advocate for Robert:

"It was a difficult time because the school didn't want to listen to any other perspectives about what they might be able to do," said Wendy. They were insistent that it was the only thing that would work. It made you feel frustrated that they couldn't come up with something else as this was obviously harming your child. It was like torture."

SPEAKING OUT ON SECLUSION--Robert Ernst, subjected to seclusion practices as a first grader, talks about his experiences at the introduction of the "Keeping All Students Safe Act" earlier this year.

When asked what advice she had for parents dealing with these issues, Wendy Ernst responded: "Tell them to stand up for your child. Believe your child. And insist on having reports in writing . . . They can't say they didn't do that. Because it's in writing." Wendy added that restraint and seclusion are "too often is the first response, when it should only be used as a last resort when someone is in imminent danger."

What about parents who speak up? What are the risks involved for parents who can find themselves being singled out for speaking about these issues publicly and trying to help their children?

All too often the response of school districts when confronted about the use of restraints and seclusion is to deny, minimize and blame.

In Hawaii, in early 2013, Hawaii News Now reported that the families of six disabled students had come forward with allegations of abuse by school staff. Cell phone images of one student being held down by the neck were released, and a lawsuit alleged that another student was forced to eat food she had thrown up. According to the news organization: "At the time of the allegations, the state said its own investigation had uncovered no evidence of abuse and that the women who made the initial claims were lying. Earlier this year, an administrative law judge ruled the students had been physically and emotionally abused by school staffers and suggested that the state had botched its investigation into the abuse."

As a result of the actions of the parents and news coverage, a state bill that prohibits the use of seclusion and physical restraint on students in public schools, and protects some of Hawaii's most vulnerable students, was signed into law by Governor Neil Abercrombie.

In Lexington, MA, a survey of parents of kids with special needs found that of 61 parents commenting on their communications with the school, 23 of them (37%) indicated that they felt intimidation and the fear of reduction of services, or not receiving the services their children need, as reasons for not feeling comfortable raising questions and concerns.

One Lexington parent stated in the report, "I am afraid of being considered a trouble maker and then my child's services will suffer." Another parent commented, "There is retaliation for raising concerns in the form of delayed meetings, limiting access to teachers, and even filing false child abuse reports."

Keeping All Students Safe Act

To curtail the use of restraint and seclusion in schools across the country, Senator Tom Harkin and Rep. George Miller have introduced the federal Keeping All Students Safe Act.

"These harmful practices, referred to as seclusion and restraint, are commonly used as disciplinary measures, most frequently on students of color and those with disabilities," wrote Rep. George Miller regarding the bill, which would ban restraint and seclusion except in cases where the student or others are in imminent danger.

"There's a patchwork of largely lackluster state laws and regulations that leaves thousands of students vulnerable to abuse each school year," said Miller in a recent letter. "Despite federal laws limiting use of seclusion and restraint in hospitals, psychiatric facilities, community-based facilities, and even prisons, no such federal law exists to restrict this abuse in schools. Few states provide protections for all children by law, and many states have weak legal protections or no protections at all."

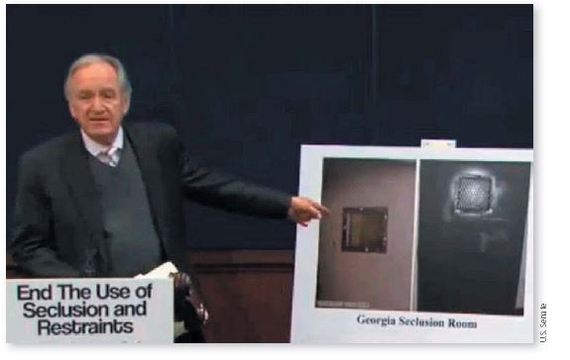

CONGRESSIONAL ACTION--U.S. Senator Tom Harkin introduced the "Keeping All Students Safe Act" on February 12, 2014.

Opposition to the legislation comes from the American Association of School Administrators which objects to the requirement that restraint can only be used to avoid serious bodily injury since, according to the AASA, it would be impossible for school staff to make a determination about whether the risk of injury in a crisis situation could lead to serious bodily injury. The AASA is also arguing that the data collection provisions of the act as well the demands on staff training will be both burdensome and costly for school districts.

But Sen. Tom Harkin rejects these reasons for allowing these practices to continue.

"These old myths, these old ways of treating people have got to go by the wayside," Harkin said at the Feb. 12 press conference introducing the Keeping All Students Safe Act. "You have to wonder how many young lives have been so severely damaged that they cannot be fully included members of our society."

Harkin compared the seclusion rooms he has seen in schools to a recent trip he took to Cuba.

"You know what that reminds me of, folks?" said Senator Harkin, gesturing to the photograph of a school isolation room. "You know where I was last Saturday? I was in Guantanamo, Cuba . . . We went and saw the cells where the keep the most dangerous terrorists in the world. And you know what their cells look like? Like that. And that's where they're putting our kids, in schools."

Originally published in the Autism File.