For many residents in southern Illinois dealing with the fallout of a sanctioned coal and fracking rush, the time has come to revamp the historic Illinois South organization and its role in providing impacted residents with a voice in state and federal regulatory matters.

Call it deja vu all over again.

And perhaps no one understands this better than Rev. Dave Ostendorf, the co-founder of the Illinois South citizens group in 1974, and a long-time community organizer for civil rights in Chicago and across the heartland and nation.

"Building critical mass around the stories--of people and communities most directly impacted or the stories of devastating environmental impacts--seems to me like the challenge that still lies ahead," he told me in a recent interview. "And the challenge that the good folk of Southern Illinois face."

Based in the historic coal town of Herrin, Ostendorf and his co-workers effectively organized local communities to use their stories and voices to take on the rogues elements of the coal industry during a coal rush four decades ago. Illinois South organized locally-led workshops, conferences, farmer's markets, and published a series of fact-finding pamphlets, including "Who's Mining the Farm: A report on the energy corporations' ownership of Illinois land and coal reserves and its implications for rural people and their communities."

At the invitation of city officials in Sparta in 1978, for example, Illinois South organized a series of public hearings that allowed local residents to have a hand in developing unprecedented protections against strip mining operations by Peabody Coal.

"The Illinois South Project's participation with the people of Sparta in this process," Ostendorf wrote years later, in Thunder at Michigan and Thunder in the Heartland, "taught us that social change organizations can play a critical role in such negotiating process without compromising their own goals."

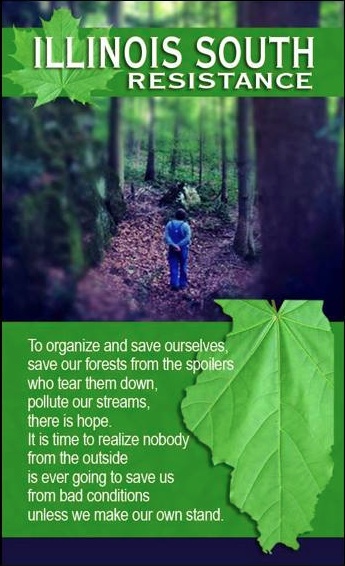

new Illinois South courtesy of Matthew Schultz, Graphic Design

That was then; but is today a similar story? While Illinois South eventually transformed into the Illinois Stewardship Alliance and shifted to farm matters, many of the same issues facing coal and extraction areas have come back into play in southern Illinois.

And come back in a fury. It's bad enough that the state of Illinois is ensnared in a national disgrace over failed coal mining regulations and protection measures.

But the recent debacle over Illinois' admittedly flawed new fracking regulations, hammered out last spring in backroom negotiations between gas industry and state officials, and a handful of inexperienced and non-impacted environmental representatives, was a flashback to 1977 for many long-time activists, when compromising Big Green organizations and legislators abandoned the strip mining abolitionist movement and opted to "regulate" strip mining, instead of banning its undeniable wrath of destruction in the coal areas.

In 1977, in the afterglow of the OPEC energy crisis and a new scramble toward coal production, President Jimmy Carter signed the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, an admittedly "watered down bill" that would enhance "the legitimate and much needed production of coal."

Few residents in the impacted coal mining areas agreed. An Appalachian coalition working with the heartland and western advocates considered the bill "so weakened by compromise that it no longer promised effective control of the coal industry or adequate protection of citizens' rights." Writing in the Illinois South newsletter in 1987, on the tenth anniversary of the mining law, legendary Illinois activist Jane Johnson declared: "People in the cornbelt felt betrayed."

A similar feeling of betrayal was issued this summer after Illinois passed its fracking regulations.

The more things change, the more they stay the same, as the French proverb goes, and perhaps it's particularly apt for Illinois: The French were the first Europeans to discover coal in the Americas, along the Illinois River in the 1600s, that ultimately launched the first coal industry on our nation's soil.

Now based in Wisconsin, on the edge of frac sand mining operations, Ostendorf took part in an interview on Illinois South and today's challenges in the same region.

Jeff Biggers: Describe the circumstances that led to the founding of Illinois South in the 1970s?

Dave Ostendorf: The energy crisis of 1973--when OPEC launched an oil embargo curtailing shipments to the US--prompted public panic in long lines at gas stations nationwide, and growing calls for (the ever-elusive) "energy independence" that would allegedly "free" the country of its reliance on Mideast oil. Illinois politicians and coal industry moguls seized the opportunity, and began touting Illinois coal as a primary answer to the nation's energy needs and future, particularly in light of the "promise" of coal gasification--the new technology that would convert the resource into oil.

From their home in Godfrey, my parents began sending me newspaper clips about the situation; I was in my second and final year of the new Environmental Advocacy Masters program at the University of Michigan School of Natural Resources following seminary and ordination in the United Church of Christ. The situation piqued my interest. I began talking with Roz, my spouse, about it, along with others in the UM program. Then Governor Walker announced a statewide conference on Illinois coal in Springfield, and Roz, our UM friend and colleague Mike Schechtman, and I attended the conference to "get the lay of the land." In the winter/spring of 1974 we began serious discussions about heading to Southern Illinois to begin working with/organizing communities to address the impacts of the new/emerging coal boom; I did a road trip in the spring of that year to talk with folks and make another assessment before we took the plunge.

In May, 1974 we (Roz, Mike, our infant daughter Kyra, and I) loaded up a small U-Haul truck, got in our cars, and headed to Godfrey, where we based for several weeks while we scouted a locale for our work. The weekend after our arrival we attended the annual meeting of the Illinois South Conference of the United Church of Christ (my home Conference) where we presented our concept, got a very warm and engaged reception for it, and left with a commitment of financial support ($5,000!) for each of the ensuing two years. We were elated! We found an old (coal heated...) house in Carterville, where we lived collectively and had our "office." The Illinois South Project was launched. We moved the operation to Herrin later, once we had become somewhat established and had sufficient funds to pay real office rent.

JB: How would you depict the relationship between the coal industry and state agencies and politicians in those days?

DO: Hand-in-glove. The Walker administration was pushing coal development hard--all the usual jobs/economic development blather. The agency apparatus of the state was mobilized to jump in the industry's lap with the Governor as he laid the foundation to save America with Illinois coal (right...). Ironically, in going back just today to check some dates/relationships, I found a link I had not been aware of before. Walker was a law school student with George Kelm, and later they were partners at the same Chicago law firm and active in Dem politics. Kelm went on to head Sahara Coal, and the Woods Foundation. I was also reminded today of Taylor Pensoneau, the St. Louis Post Dispatch political reporter who covered Walker (and later co-authored a book on him), and who went to work as VP for the Illinois Coal Association in 1978. Interesting indeed.

We didn't really have the capacity to do the deep and necessary political research work that may have strengthened our hand as the ISP emerged in those early years. In the current context I think that this is absolutely essential and, hopefully, somewhat easier given the availability of and access to web-based information, links, and relationships.

JB: Many Big Green groups accepted SMCRA as compromise on stripmining. Did you and Illinois South agree?

DO: A challenging question. We pushed hard for prime ag land preservation, and for the highest standards of land reclamation in the Act. We were still pretty organizationally young in the 1975/76 period and I think it's safe to say that we did not have the experience or the clout or the base to seriously impact the legislation. In retrospect and in light of the power of the coal industry in that day, I think it's quite accurate to say that the Act was a compromise that, in the long run, of course, did not serve the interests of impacted communities.

JB: Why do you feel regional representation, especially among impacted residents, is necessary on state and national regulatory decisions? In Illinois, in particular, do you think environmental reps in Chicago should speak on behalf of people in southern Illinois?

DO: The age-old political challenge of Illinois life: Chicago vs. downstate. I'll never forget one of the first meetings Mike and I had with an area legislator, who told us up-front that the only way anything got done in Southern Illinois was via compromise with Chicago politicos. The Illinois divide is deep and lasting, a reality of political life that must be dealt with creatively by folks on the ground whose lives and communities are most directly impacted by state/national regulatory decisions.

When it comes to environmental groups/reps in Chicago speaking on behalf of the people of Southern Illinois--no way unless those who are/have organized in the region have agreed that they might do so, and that their positions reflect the will of the people of the region. Period.

JB: Given the recent regulatory compromise over fracking in Illinois, against the wishes of downstate citizens groups, do you see parallels between 1970s and today?

DO: Certainly. I think, however, that one of the key differences between dealing with the coal barons of the past and those (coal/oil) interests of today is the relatively slow speed by which deep or surface mining developed vs the comparatively lightning speed that fracking has developed and continues to expand. The difference, to me, is astounding and presents significant (and perhaps unparallelled?) challenges to communities/regions confronting fracking.

The impacts of "conventional" deep and surface mining have been known for decades and generations, as have all the trade-offs and compromises thereof, if you will, and the struggles of workers and communities to minimize those impacts has been virtually unending and continuous to this day--as you have written about so powerfully. Those struggles and fights must continue!

Fracking, on the other hand, is taking the nation by storm. The proverbial jury still seems to be out re its environmental impacts--i.e., even though those impacts are increasingly known, public opinion still seems unshaped about whether fracking is ok or not... and is leaning, in my estimate, toward indifference in light of the perceived economic benefits.

In my own silica sand township here in Wisconsin's Mississippi River valley a new sand mine was considered and approved so quickly that there was little real opportunity to assess its impacts, nor did residents have much information to be able to do so. This wasn't simply a quick and successful political move by the sand company as much as it was a wake-up call to area residents, who have lived with sand mining for years and who are relatively unaware of the sand mining onslaught that the industry will likely precipitate.

I'm not sure yet what this means strategically re how best to take on fracking mania. Theoretically, an immediate, pressing issue should make it easier to organize/mobilize people. But again, it feels like we don't have enough of "the goods" on the adverse impacts of fracking--especially the stories of people and communities most directly impacted (except for the boom towns of ND), or the stories of environmental impacts devastating/debilitating enough to get peoples' attention (e.g., the loss of water tables). Building critical mass around the stories seems to me like the challenge that still lies ahead-- the challenge that the good folk of Southern Illinois face.