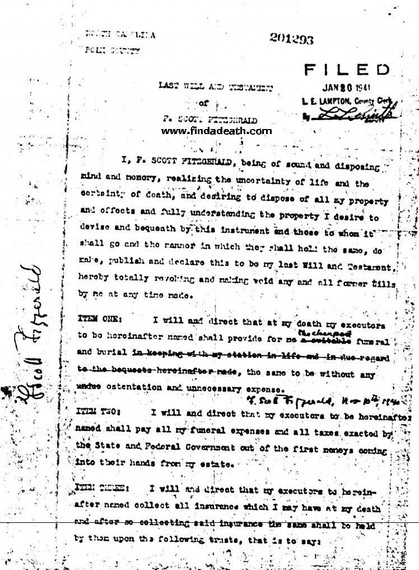

Scott Fitzgerald's will as filed in Los Angeles, January 1941, via findadeath.com

He died in Hollywood on December 21, 1940, eating a chocolate bar and making notes in pencil on a football story in the Princeton Alumni Weekly. The last words F. Scott Fitzgerald ever wrote complimented the author of the story: "Good prose." At a time when college football was as popular in America as pro football is today, F. Scott Fitzgerald's interest in his alma mater's team was not nostalgic or pathetic; after all, Princeton played in the first college football game in America, were national champions repeatedly in Fitzgerald's lifetime, and still hold the record for championships -- 28 -- according to the NCAA. He was enjoying what he read when a massive heart attack lifted him to his feet for a moment, next to the fireplace in his girlfriend Sheilah Graham's apartment, and then threw him to the floor, dead.

Fitzgerald had drawn up his last will and testament in Polk County, North Carolina, before he left for Hollywood in 1937. It was filed less than a month after his death in Los Angeles, on January 20, 1941. In it, he continues to provide for his wife, Zelda, who was institutionalized at Highlands Hospital -- in the county in which he had made his will, while visiting her at Highlands -- and for his only child, daughter Scottie. Unhappily, there was very little when he died to distribute to anyone. Fitzgerald was in debt, partly owned an old car, and had little else worth much, at the time: books, papers, manuscripts. All of these that survive are now worth so much today, and nothing then.

Fitzgerald knew that, and the month before his death -- after cardiac episodes that had left him sick, exhausted and frightened -- had changed his will accordingly, and movingly. In the first itemized paragraph, to do with his funeral, Fitzgerald's original directive was that his funeral and burial should be "suitable" and "in keeping with my station in life and in due regard to the bequests hereinafter made, the same to be without any undue ostentation and unnecessary expense."

On November 10, 1940, Fitzgerald crossed out "suitable" and wrote in, above, "the cheapest." He also deleted the language about his station in life, bequests, and the word "undue" -- directing that he should be buried "without any ostentation and unnecessary expense." He dated the changes, and signed his full name in the margin to make it all official. His signature is as swirling and elegant as ever.

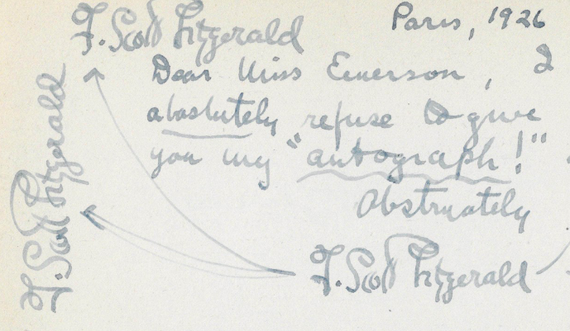

In 2012, Christie's sold a Fitzgerald note from 1926. Refusing to give a Miss Emerson his autograph, with characteristic humor few critics bother to realize he had, Fitzgerald signed his name five times for her -- four on the "refusal" page and one on the back. The $3750.00 someone paid for this one piece of paper would have, in 1940 dollars, paid all Scottie Fitzgerald's college fees as well as Zelda's hospital bills -- with money left over to live on.

Fitzgerald's note to Miss Emerson (detail), via Christie's

Anne Margaret Daniel 2014