This is Part Four of the seven-part series, XX CHROMOSOCIAL: WOMEN ARTISTS CROSS THE HOMOSOCIAL DIVIDE. See Part One, Part Two, and Part Three on HUFFINGTON POST.

It seems an enlightening enterprise to look at the visual representations of rape and sexual violence made by women and compare them with those made by men. The trouble arises in trying to find historically significant artists of both genders sharing the same temporal and cultural backgrounds to help us establish a credible basis for dialogue between them. But from the start, the sad yet all-too-obvious fact makes itself known: If there is any significant artistic dialogue on rape between the sexes, it remains obscure to art history.

During the nearly three millennia in which sexual violence against women have been prominently portrayed in Western, non-pornographic art, except for the single and pivotal exception of Artemisia Gentileschi's Susanna and the Elders, painted in 1610, the most renown and significant renderings in pre-modern painting and sculpture are made by men. And Gentileschi's thematic and pictorial approach to extreme sexual coercion (in which she is seen being threatened with certain execution for an infidelity she didn't commit unless she consents to the elder's sexual demands) is defiantly in opposition to the majority of canonical scenes made by men before and since.

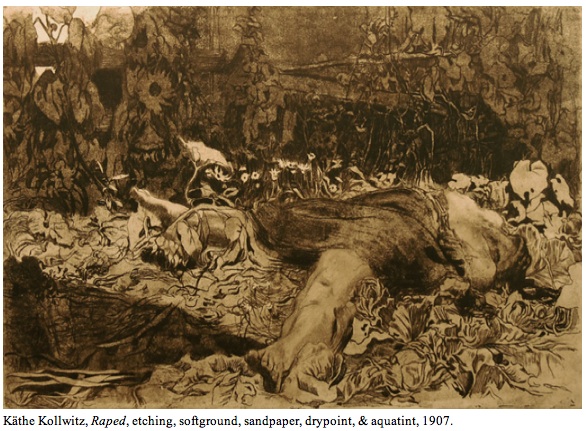

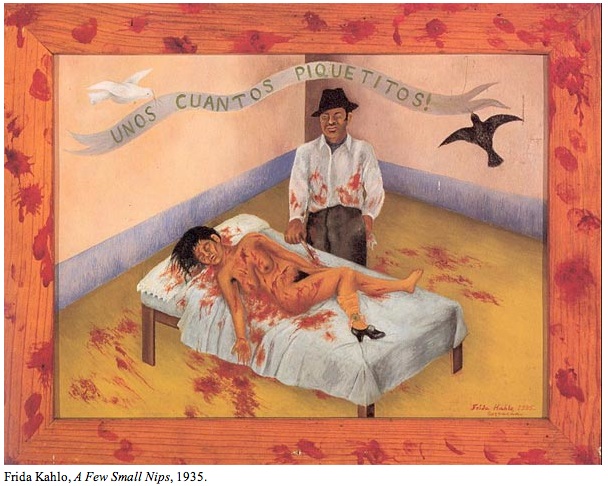

The early 20th century hardly fares better, with only two of the most notable depictions of sexual violence having been made by women: Käthe Kollwitz's 1907 etching, Raped, and Frida Kahlo's 1935 painting, A Few Small Nips. And as irony would have it--or perhaps male homosocial resistance--from the 1970s onward, as women began to collectively surround the issue of rape and sexual violence with acutely critical art, few male artists showed an interest in contributing to the developing visual discourse.

We're left with the representations of rape made by men of history and women of today, a lopsided, cross-cultural comparison of millennia to decades and presumptions of noble entitlement to rights of democratic dissent. But it's from these dramatic differences between the artistic tenors and depicted ethical values of men and women, ancients and moderns, that we can discern how and why rape not only persists at such a high incidence in civilization, but as well how visual representations factor into this persistence. Apart from the obvious ethical and political issues that arise with representations of rape, we can hope to also discern the deeper affinities aligning the artists, patrons, and viewers with the victims or the victimizers depicted.

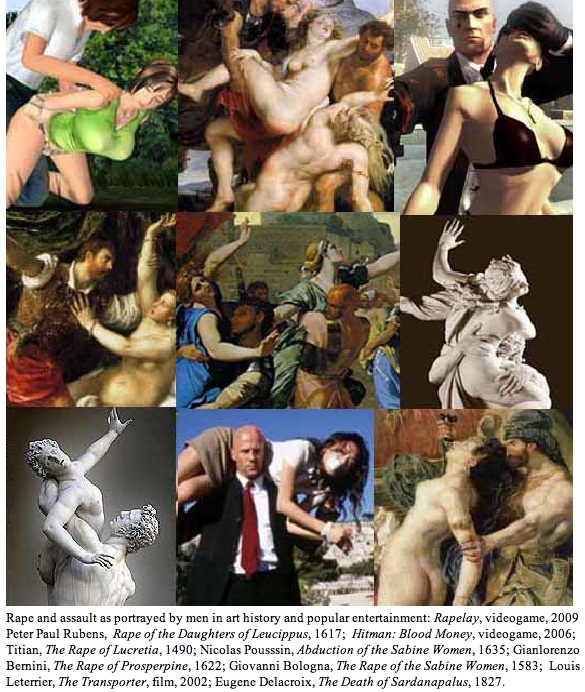

With historical art, unless we are furnished with documentation on how the art in question was received by its patrons and the public, we can only surmise how it was culturally valued by the frequency with which we find its subject commissioned and collected. It tells us a great deal that the rape and abduction of historical or mythological subjects was a highly popular theme in Greek, Roman, and post-Renaissance Western European art. (An abundance of Chinese paintings and Japanese ukiyo-e prints depict the rape of women and young men with expert craftmanship, but even the most noteworthy artistically are of an explicitly erotic character made for private pleasure, not public viewing or social commentary.) Most telling is that the depicitons made by men over the ages overwhelmingly portray the act of rape from an exterior point of view--as if it is performed in a theater that we look out onto to watch a climactic, narcissistic, even heroically idealized adventure of male self-realization in action.

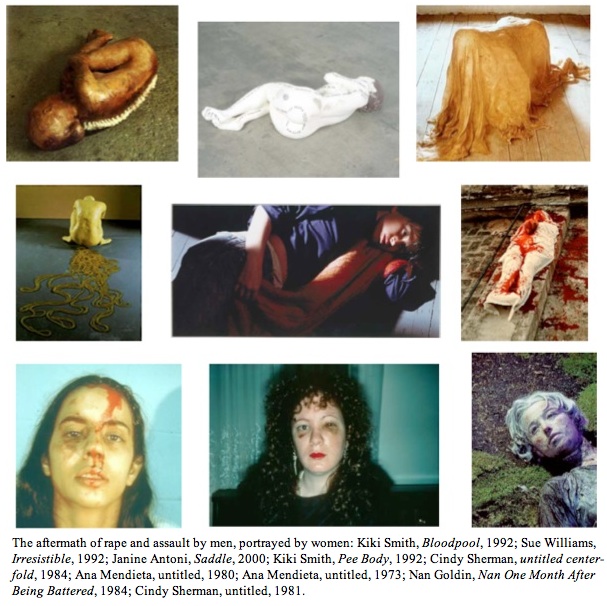

In stark contrast to this exterior view of rape that men have produced stands what may best be described as an interior apperception by which contemporary women artists, like Gentileschi, Kollwitz and Kahlo before them, choose to render the aftermath of rape and assault rather than the actual acts being perpetrated. Instead of the women presenting us a vividly articulated window onto rape, we are drawn into the shattered psyche of the rape victim through a kind of black hole punched through her and from which drains her life force so relentlessly, she is made blind, immobile and drawn into the deepest, darkest isolation--a catatonic cocoon of numbing self-annihilation that, if she survives, long outlives the male's momentary and insensate narcissism.

The difference between the exterior and the interior views of rape is a seemingly simple point of psychological and visual perspective, yet one that speaks of a profound estimation by the artists, their patrons and audiences, on whether to favor the representation of sexual violence as aesthetic and dramatic action, or as ethical and psychological empathy. Perhaps more crudely yet accurately put, it's a matter of whether we wish to be made more intimate with the physical and psychological experience of the rapist or the rape victim. This doesn't mean that an artist who chooses that we see the rape from an exterior view is sympathetic to the rapist. It does mean that if we are homosocially conditioned to value action and violence through repeated visual reinforcements, our ability to empathize with the victim depicted may be significantly diminished. At least this is what our art-historical comparison of the heterosexual rape as represented by the male preference for theatrical action appears to testify.

The starkly different responses accorded representations of rape by male and female critics and art historians also indicates that few other artistic renderings past or present seem capable of conveying the polarizing divide of gender as do representations of rape. But then we don't need a comparison of artistic renderings to tell us there is no deeper, more devastating chasm of separation between men and women than that rasped out by the male will for sexual domination.

Yet even this dark and brutal chasm of difference doesn't necessitate that we explain the gender divide over rape and its opposite representations by favoring theories of essential biological gender differences--the kind that offer apologies for the clichés of the inevitable male intoxication by, and female surrender to, testosterone and estrogen, while offering little to the equation of social power enacted in rape. Put simply, we needn't rush to models of nature when the models of nurture are proving to be more fruitful to our understanding of how heterosexual rape and sexual violence is an effect of our separate male and female enculturations--in other words, our homosocialization. And that homosocialization largely relies on visual means of reinforcement, a great degree of which is supplied by artists at all levels of image production.

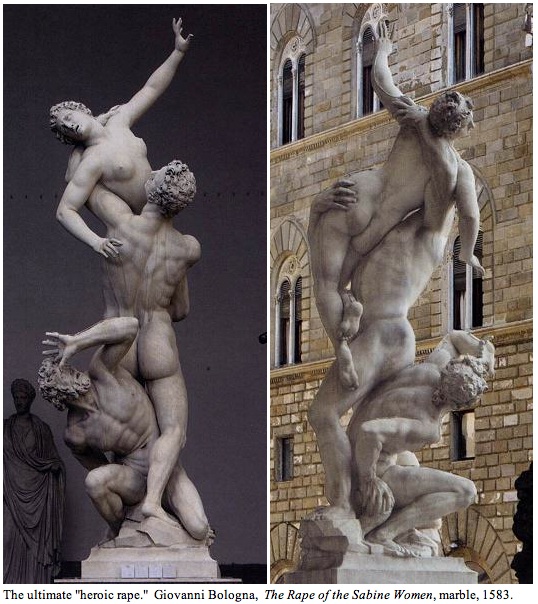

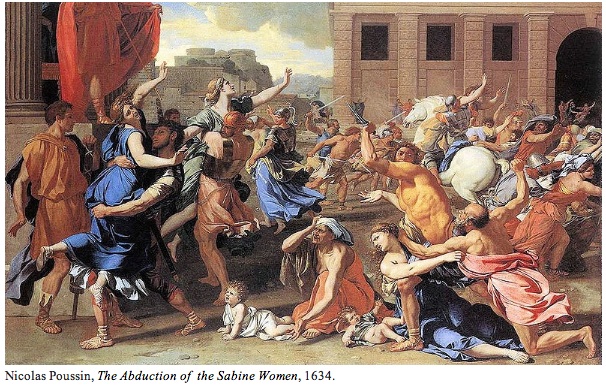

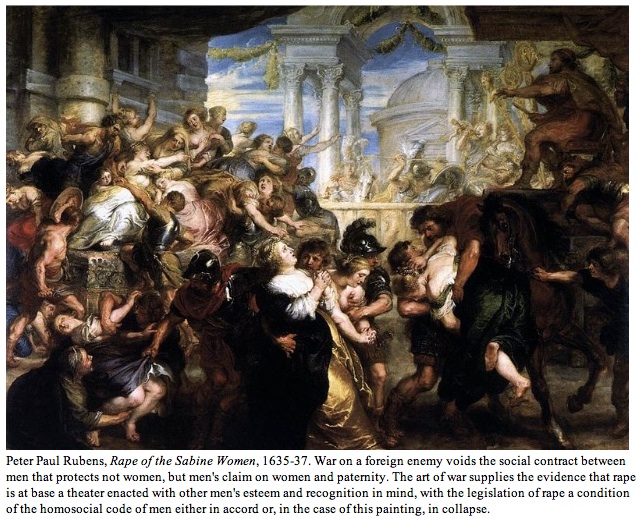

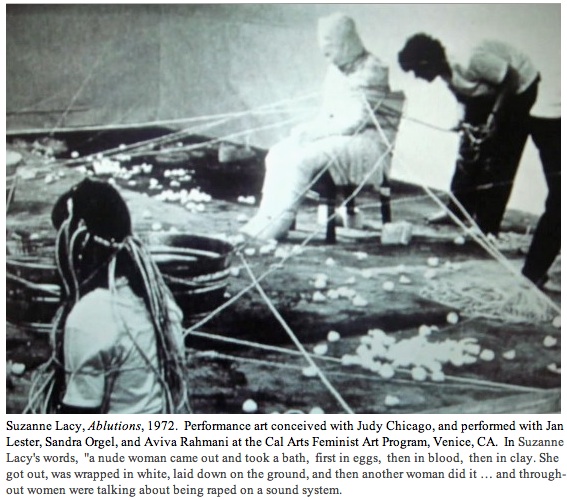

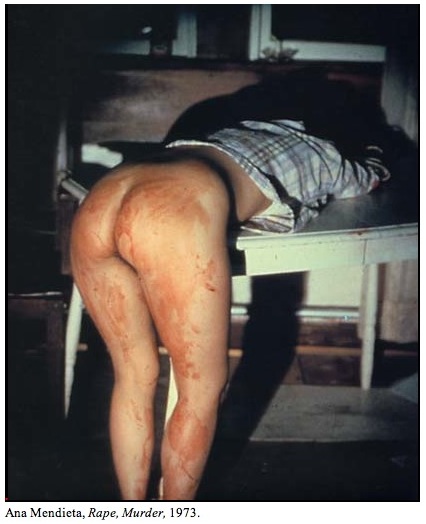

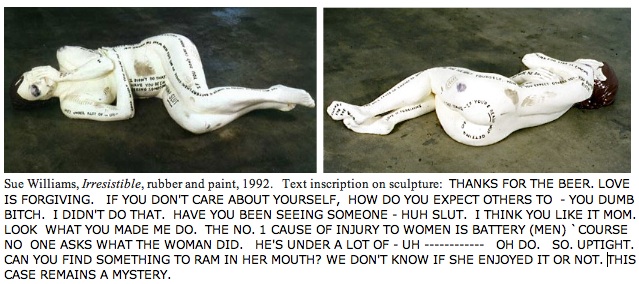

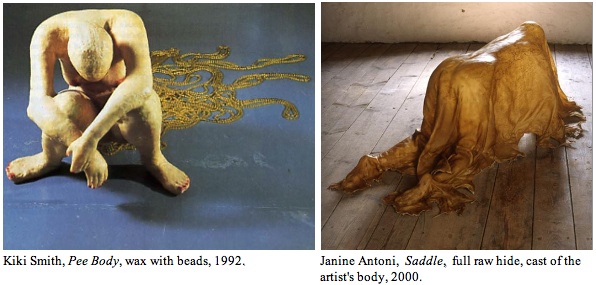

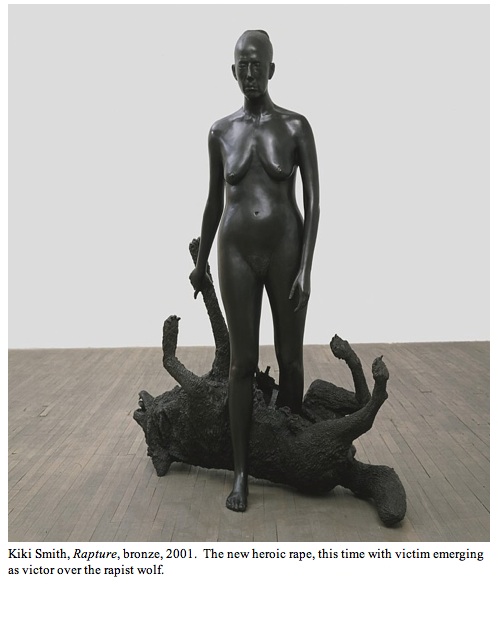

With image production no longer exclusively in the hands of men, the interior representations of rape and assault introduced with the art of Gentileschi, Kollwitz and Kahlo, and which emphasize the aftermath of rape, have since been expounded on by Suzanne Lacy, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin, Kiki Smith, Sue Williams, and Janine Antoni. Together the women have elevated an art of ethics and empathy above aesthetics and dramatic tension as they turn the traditional and male representations of rape inside out to display, effigize, mimic, and analogize the ravaged and broken bodies that betray the real-life effects of rape. In so doing, the artists deflate the visions of virility marking representations of gratuitous rapes, specifically those masterpieces that Susan Brownmiller famously characterized as the tradition of "heroic rape"--those iconic sculptural and painted abductions of women that the larger public recognizes best in the masterpieces by Giovanni Bologna, Gianlorenzo Bernini, Nicolas Poussin, Peter Paul Rubens, and Titian.

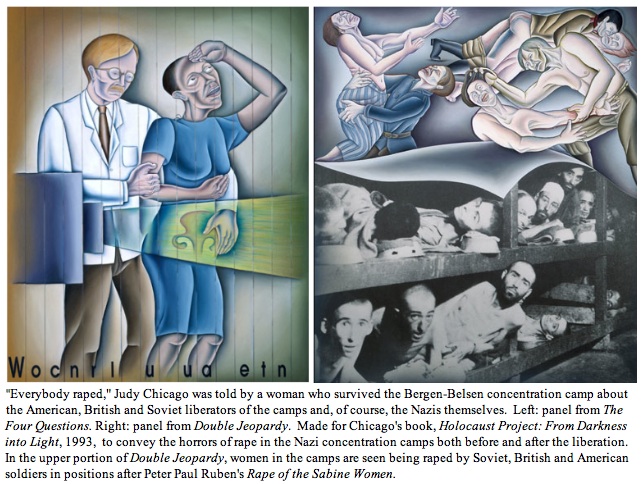

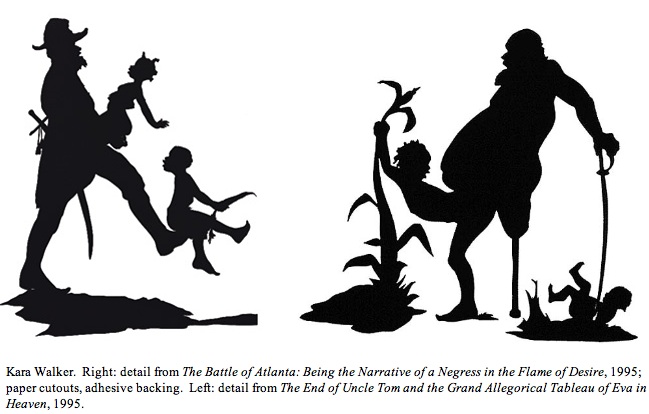

Naturally there are exceptions to this formula. Judy Chicago and Kara Walker break out of the women's interior view, and thereby disassociate themselves from the art and psychology of victimization, by visually narrating an exterior theater of rape closer to those made by men. Except that the men are now cast in criminal documentations (Chicago) and lascivious lampoons (Walker). Less polemically, Nan Goldin, in her famous photographic series, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, represents both the XX and XY sides of the chromosocial divide, heightening the ambiguity that gives way to real-life allegations of women's enablement of their assailants through the deep dependency keeping women attached to abusive men. But even through the haze of Goldin's ambiguity, the potential for sexual violence to erupt remains in sight, and the ultimate message conveyed by her frank lens equates rape and assault with the forced dehumanization of women and, ironically, with an all-too-humanizing view of the fragility and cowardice, not the heroism, of men.

But as women's art stimulates artistic activism, a kind of representation of heroic rape has trickled down into popular, if diluted and often insidious visual entertainment with the advent of violent video games, anime and manga, graphic novels, and the grist of cinematic gore. Here the heroic-turned-criminal rape is played and replayed (or "rapelayed," in the much condemned Rapelay game) with relish as female characters and avatars are overpowered, raped and tortured, not only by male sociopath criminals, but psychosomatically by the legion of men who voyeuristically identify with, and in video games technologically merge with and steer, their rapist alter-egos.

In reaction to the spectacular and historical heroic rape scenes and today's popular simulations of criminal rape, the majority of the women's representation of sexual violence has purposefully voided visualization of the rapist altogether. And yet without being told, we recognize immediately that all the works implicate the male rapist in absentia through the abjection of his victim--the animalistic yet no less psychic bruise he has marked them with, and by which he, in his derangement, imagines to retain possession of them. Whether such interior visions of rape made by women are the effects of experience or empathy, they are too visibly "of a mind" to be informed by any other commonality than the homosocial conditionings and repressions of women over centuries, if not millennia.

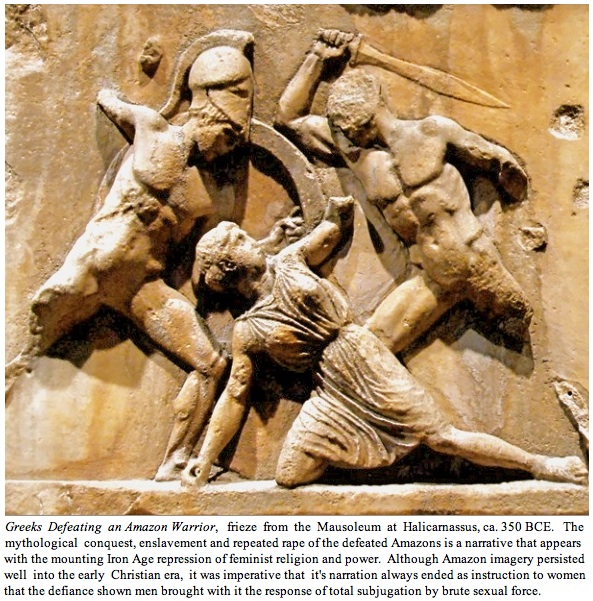

Taken as a whole, the comparison of periods and cultures explains the desire of so many women artists to exhume and re-codify historic iconographies of rape that the presiding male homosocieties of the time had sanctioned as tasteful depictions of abduction and assault on women, so long as they remained within the tradition of the "heroic" male genre. The intent of the women, of course, is to dislodge and dissolve the legitimacy that long reassured the male homosocial tolerance of, if not the enablement and complicity with, the widespread rape and abuse of women.

The reality of rape's traumatic effects rings truer to sensible modern audiences than the heroic rape, even if its visualizations are harder to digest than the exalted and romanticized embellishments that artists historically used to cover over that reality, especially as a large part of the world has recognized that feminism rightfully made rape an equation of power. But to understand rape homosocially, and more particularly to understand the historical representation of rape in a light that makes the discreet codes of rape embedded deeply within male homosocieties understandable, we must look beyond the power that rape gives to men over women. We must come to see how rape also endows and reinforces the power that men hold over other men.

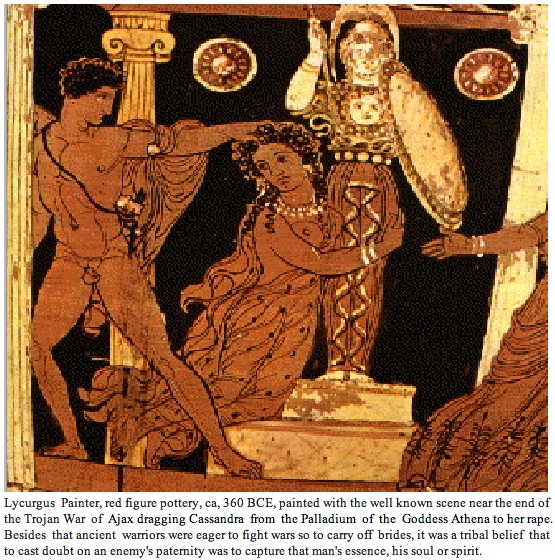

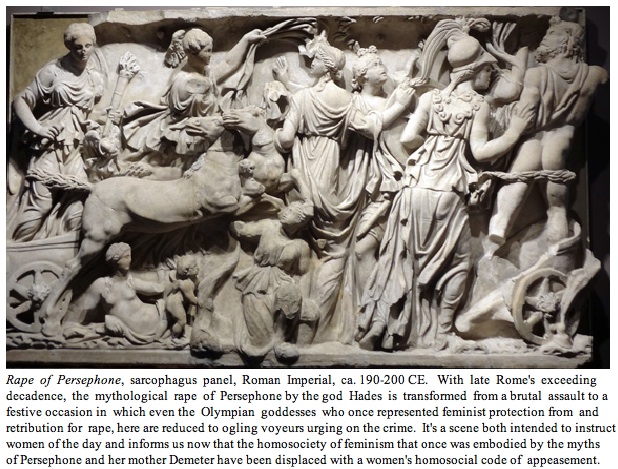

To understand this, we need only study the many art historical representations of heroic rape that appear, firstly, in the Attic vase paintings and sculpture of classical Greece, then, as it is recast by the Romans as a celebratory event that even women and goddesses are eager to partake in (see Rape of Persephone, above), as a process of male homosocialization. But we also need to consider how these depictions embody the theater of heroic rape authored nearly three millennia ago by the Greeks, and specifically by Homer as he turned the widespread abduction of women from enemy states during war into a primary literary motif of The Illiad.

It is warfare that gives legitimacy to the heroic rape, makes the representation of heroic rape "high art." Here the notion of the male homosocial city- or nation-state supplies the "justifying" ethos that extends the male theater of rape well beyond patriarchal authority over women. For in the heroic rape, the mass abduction of foreign women is revealed as more than a bid for homosocial legitimacy within the fraternal order of men. It is also an assertion of the power men accumulate over other men through the violation of the "other men's women." And when the other men are from an enemy nation, as we see them to be in art depicting the rapes of the Sabine and Trojan Wars, the abduction and rape of the enemy's women is represented as valor in service of the state.

With all art inherently a theatrical form, the visual art of history is the richest record we have of the theater of men's power over women and other men through acts of sexual aggression and violence. And in this visual theater of sexual power we find an array of homosocial codes instilling and reinforcing the behaviors of both men's and women's homosocieties. It should surprise no one that among these theatrical behaviors we find men acting out male same-sex attractions and rivalries, whether they be homoerotic or, more frequently, wholly fraternal, filial, and obligatory to patronage and state.

And yet we learn nothing more glorious about the homosocial sanctioning of certain conditions for rape from the historical masterpieces than we learn about the modern valuation of gratuitous rape from such video avatar games as Rapelay and Grand Theft Auto. And this is our prime lesson from comparing high art with popular visualizations: We learn that the representation of rape imparted by the grand historical masterpieces are no more high minded in their conversion of the thrill that comes with imagining to descend into some historical pit of savagery than are the gratuitous displays of rapist adventures in film gore and 3D avatar videos today. At least the historical masterpieces are reputed to have been made in a societal context that countered the visualization of rape with moral standards. But for the disadvantaged youth who have no more substantial homosocial reinforcement of men's bonds, rivalries, and enmities than other enthusiasts of computer-simulated criminal genres, the criminal codes represented in these genres are the primary informants of their emerging world views.

But even the theater of rape that is conveyed by the historical masterpieces can instill a picture of an audience to rape in the psyche of the rapist. When combined with the popular entertainments the rapist receives both a "high" and a "low" cultural reinforcement of rape as theater. To the unstable or easily impressionable mind, the theater of rape portrayed in art and entertainment can even motivate the rapist's assault. Unlike the murderer, the rapist purposefully leaves behind a witness--his most immediate audience. The rapist also knows his theater will be relayed to the police, the examining physician and nurses, friends and relatives of the victim.

But there is also his inherent primary audience, that which the rapist carries with him and for which he truly performs, whether consciously or unconsciously--the homosociety of men whom he believes informed, and continue to reinforce, the codes of his imagined manhood. Such homosocial codes, as varied as they are from culture to culture, enclave to enclave, if not legitimize rape in a civilized society, certainly legitimize the representation of rape as heroic and acceptable. These are the same homosocial codes that serve as the rapist's script and scenario of reinforcing masculinity. They inform him there are others like him, and in this respect the rapist is emboldened in his crime by the image of himself before an audience of his male peers cheering him on, and even some women, as he assumes his imagined biological right and imperative to possess and overpower a woman or weaker man.

How far this callous indifference to rape spreads through the mainstream of male homosociety is revealed only during times of war, when the contagion of rape spreads exponentially, especially when it is reinforced by military enclaves comprised of all-male actors and, except for the women victims, an all-male audience. Needless to say, war and military isolation have traditionally constituted one of the great male-homosocial theaters.

Yet even so astute a critic of male power structures as Judy Chicago only discovered the truth about some of "our boys at war" when she in the early 1990s began work on her book, Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light. As she was preparing to paint a series of panels depicting Jewish women in concentration camps being raped by their German captors, Chicago was told by her project advisor, a woman who had survived the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, that "Everybody raped." Meaning not just the women's Nazi captors, but also the American, British, and Soviet soldiers who liberated the camps.

With the most ancient and renown representations of heroic rape depicting the rape of war (the rapes of the Trojans by the Greeks, of the Sabines by the Romans), we can see that the source of the heroic rape, at least in art, is to be found in the power men believed could be acquired over the enemy from the rape of the "enemy's women." Besides that ancient warriors were eager to fight wars so they could carry off brides, it was a tribal belief that to cast doubt on another man's paternity was to capture that man's essence, his soul or spirit. Today we would say to deprive him of his pride, even the reasons for which he lives. To many men under the constant and extreme duress of war, taking another man's wife sexually against her will presents itself as an act of enmity more potent than death.

Whether or not the newly-exposed interior representations of the rape victim made by women can succeed in carving through the ancient male homosocial coding, like that code which informs many men of the delusion of the heroic rape, remains in question. The aversion of many men to women's representations of rape, or to the thought of making their own art of rape in the new arena of gender parity, is a demonstrable effect of men's homosocial enculturation, much of which is visual in nature.

This may in part account for why, with the new millennium, we've begun to encounter imagery not of women as victims of rape, but as victors over rape. Paradigmatic of this development, Kiki Smith' 2001 bronze sculpture Rapture, embodies a woman stepping out of the ruptured corpse of a wolf that had devoured her. Whether or not the work's title is an alliterative play on words (the rupture of rape = women's rapture), Smith has embodied every woman's wish for a time when women have conquered rape.

On 11/14/11, Suzanne Lacy was added to this post, along with the photo-document of her 1972 performance, Ablutions. The original post did not include her work, nor mention of any performance art.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.