NEW YORK -- The fast food protests that have swept the nation in recent years, including demonstrations in dozens of cities on Thursday, introduced Americans to thousands of people like Flavia Cabral.

Cabral, 53, is the sole breadwinner for her Bronx family. Her husband is unemployed, so she splits her time between working at a Manhattan McDonald’s and a shipping company. Despite working two jobs, she brings home just $370 a week, far less than roughly $1,600 a week it takes to get by in New York City in a home with two parents and one kid, according to the Economic Policy Institute's family budget calculator.

“I’m the one who feeds my family, and even working two jobs, it’s not enough,” said Cabral. She was standing outside of a Burger King here Thursday morning as protesters took over the restaurant inside, drumming and chanting for a $15-an-hour wage and a union. This is Cabral’s third protest, she said, and she keeps showing up because “I believe we’re going to win. As many times as we have to do it, we’re going to to do it.”

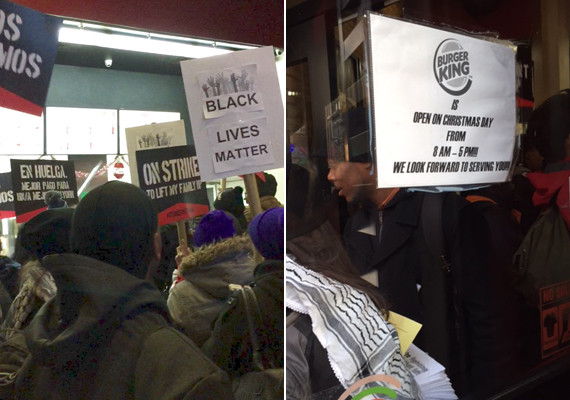

Left: Protesters hold signs inside a Brooklyn Burger King, including some that reference the controversy over the recent deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown. Right: A sign on the door of the eatery noting that it's open on Christmas Day.

Thursday’s protests, which activists say will hit 190 cities nationwide, mark the two-year anniversary of the fast food campaign. It's hard to point to concrete wins for the union-backed movement -- fast food workers' median pay hovers between $8 and $9 an hour, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and other studies, and union membership remains near historic lows.

Still, the demonstrations have grabbed Americans' attention, making more people aware of a large and growing a class of workers -- like Cabral -- who are struggling to get by.

“It’s become much more current to talk about the working poor,” said Gary Chaison, a labor relations professor at Clark University’s Graduate School of Management.

Indeed, national headlines have chronicled the effects of unpredictable scheduling, unaffordable child care and a dearth of paid sick days on low-wage workers. Ballot measures to increase the minimum wage achieved widespread success, even in red states, during the midterm elections. President Barack Obama gave fast food workers a shout-out in a speech to labor activists earlier this year, telling them that “America deserves a raise.”

Obama has also been a vocal advocate of raising the minimum wage to $10.10 an hour. Earlier this year, he set $10.10 as the wage floor for federal contractors.

“All of those things are things that you never saw discussed in public” before the protests, said Ileen DeVault, a professor at Cornell University's school of Industrial and Labor Relations.

Fast food workers have succeeded largely because their issues are so relatable. It’s easy to sympathize with the person serving you a burger and fries once you learn about their low pay and poor working conditions, DeVault said.

Organizers have capitalized on that success, using it to bring attention to low-wage workers in other industries. On Thursday, home health aides and airport workers joined the fast food protests. Standing inside the Burger King packed with protesters and signs here, one airport worker bemoaned the fact that he’s struggling during the holidays to support six kids on a salary that's close to the minimum wage.

Abera Siyoum, a disability cart operator at Minneapolis-St. Paul airport, said in an interview earlier this week that he planned to support the protesters. His wife stays home to take care of their two kids, ages 2 and 4, because childcare is too expensive. That leaves Siyoum to earn all of the money for his family. He wakes up at 3 a.m. and often doesn’t get home until 8 p.m. after working at the airport and at another job as a security officer.

“[Fast food workers] are working under the same conditions. I just want to join them because if we fight together, I think we can win together,” he said.

Protesters hold up a sign calling attention to airport workers at a Brooklyn Burger King Thursday.

In addition to showing solidarity, bringing in workers from other industries adds a level of legitimacy to the fast food protests and sheds some light on other elements of the shadow low-wage workforce, said Clark University's Chaison. “People who are on the margins of the labor force are now being talked about,” he said.

Of course, the immediate target of the protesters is still the fast food giants themselves. Demonstrators argue the chains can afford to pay their workers more. The Shake Shack next door to the Burger King here provided a stark contrast. Shake Shack pays a median wage of $10.70 an hour, according to a recent New York Times story highlighting its labor practices.

Representatives from both McDonald’s and Burger King noted in statements that their restaurants are largely owned by franchisees and that they pay fair and competitive wages.

"As a corporation, Burger King Corp. (BKC) respects the rights of all workers," the company said in a statement.

"McDonald’s and our independent franchisees support paying our valued employees fair wages aligned with a competitive marketplace," McDonald's said.

Steve Caldeira, the CEO of the International Franchise Association, characterized the protests as a headline grab aimed at growing union membership "on the backs of hard-working small business owners and their employees," in a statement Wednesday.

Still, Bienvenida Pichardo, a 57-year-old McDonald’s worker here, said it’s not enough. Pichardo, who has been working at a Manhattan McDonald’s for 11 years, said in Spanish through a translator that she makes just $8.35 an hour. Thursday’s demonstration was the first time she had come out to protest, the mom of two said, though she has been watching the demonstrations on the news for months and waiting for an opportunity to get involved.

“It was time,” she said.