The night I began reading Scott Russell Sanders's Secrets of the Universe: Scenes from the Journey Home, our new-born daughter had finally settled back to sleep in her bassinet. My wife and son resumed their rest but in the restored quiet I could not relax my mind, which flexed for solutions to my shortcomings in my work and my home.

I shined my flashlight on Sanders's opening lines, "Often I wake in the night, feeling panicky, not knowing where I am. I reach out to stroke my wife's shoulder. I peer into the dark, searching for the moonlit rectangle of a window...I listen for...the sound of my children's breathing, the drowsy chatter of birds. In the night, as in the day, I locate myself through what I love."

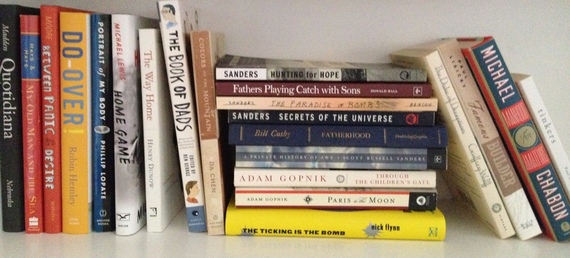

My favorite fatherhood books are a compass at the end of a frenzied day. These seven works of literary nonfiction situate me in the fellowship of other dads pursuing understandings:

1. Ben George's hunger for a "nonfiction book that took fatherhood, in all its permutations, seriously" led him to cultivating the anthology, The Book of Dads, because George wanted "to read the writers" he "admired telling" him "something true about this new experience of fatherhood." These works remind me, as Ben Fountain does in the opening essay "The Night Shift," that "Somewhere in that gray area between the extremities lies the difference between making a good life and making a bad one, and so much of it gets determined when we're tired, when we don't feel well in ourselves, when we're distracted or numbed by the daily grind and too many nights of short sleep."

2. Even on limited rest "every dad has one good bedtime story buried in him, and desperation will bring it out," writes Adam Gopnik, in Paris to the Moon. However, despite the proliferation of the instructional-how-to-be a-real-dad type of books, the evangelical, or the sentimental and often gimmicky celebrity-dad memoir, not every father has a good book in him. Perhaps this is the cause for the dismissive tone in Ben Yagoda's Memoir, a historical overview of the genre, when he writes, "Other popular autobiographical subgenres emerged for reasons similar, presumably, to the simultaneous discovery of calculus by Newton and Leibniz. Something was in the air. How else could one explain the popularity of the dad memoir (being, as opposed to possessing, one)..."

The popularity of Adam Gopnik's bestselling Paris to Moon garnered a lot of praise and is certainly worth picking up if you haven't read it. I'm a real fan of "Barney in Paris," because of the surprising turn the essay takes from lamenting how, even in Paris, the Gopniks cannot escape Barney, to a political commentary on why the purple dinosaur reminds Gopnik of President Clinton.

3. Essayist Phillip Gerard says "The subject has to carry itself and also be an elegant vehicle for larger meanings." Like those in Paris to the Moon, the essays in Gopnik's companion work Through the Children's Gate: A Home in New York imply more beyond the obvious transition of moving from Paris. For example, in "Bumping Into Mr. Ravioli," as Gopnik reflects on his daughter's imaginary friend and why she can never play with him, he sees it as an indication of New Yorkers's obsession with being "busy" and "the language of busyness that it dominates their conversation."

4. The apparent subject of those in Chabon's linked collection, Manhood for Amateurs: The Pleasures and Regrets of a Husband, Father, and Son are also merely the entry point. In "To the Legoland Station," Chabon regrets experiencing how much has changed about "Lego-building" since his youth, which "had once been open-ended and exploratory, it now had far more in common with puzzle-solving, a process of moving incrementally toward an ideal, pre-established, and above all, a provided solution." After a while, though, when the "Lego drawer" becomes a mixture of several kits, for Chabon, playing Legos with his kids has become an avenue for "the inventive mind at work, making something new out of what you have been given by your culture." This is also the essayist's job, to take a "common" and often "pre-established" way of looking at a subject, and regard it from a different angle, to recast the objects from the perspective of "the inventive mind."

Before going on to praise Chabon's work, a New York Times review qualifies, "A lot of Dad Lit makes me cringe," calling the genre a "tricky business, fraught with traps" such as "the tone-deaf presentation of some mundane, schleppy aspect of parenthood." What I wish we could do as a culture is push aside all the noise about the schleppy mundane aspects of parenting, about how children should Go the F**k to Sleep. I wish we could dismiss the alarmists and the prescriptive fix-all guide books and make more room in the publishing landscape for the humble voices confiding wisdom.

What mars literary nonfiction about fatherhood is lumping it with books that are not literary nonfiction. Such as "the cosmic-sentimental essay" which is "in any case, a kind of antimemoir," writes Gopnik, "a nonconfession confession, whose point is not to strip experience bare but to use experience for some other purpose: to draw a moral or construct an argument, make a case or just tell a joke."

5. Like several others discussed here, John T. Price's Daddy Long Legs: The Natural Education of a Father, begins with a particular pursuit. After experiencing a cardiac event, his cardiologist charges the thirty-nine year old narrator with the warning, that "if he wanted to live," beyond changes in diet and exercising he needed to "take a close look at" his "life."

6. In Great Expectation: A Father's Diary, Roche chronicles the revelations of a dad in arguably his most vulnerable state. In anticipation of their second child, the Roche's seek a new OBGYN, consider a VBAC, all while raising their five-year old daughter, and maintaining careers. There are the two miscarriages to keep in mind, the sudden loss of Roche's mother-in-law, and that they will have a new-born in their forties.

7. Throughout the meditations in Hunting for Hope: A Father's Journeys, Scott Russell Sanders "cannot turn off" his "fathering mind." In the essay "Mountain Music I," Sanders proposes a hiking trip with his teenage son to find the source of their constant quarrels. In anticipation of the trip Sanders is "primed for splendor," but soon into their hiking, the son stalks away. The active "fathering mind" can find itself consumed with his children's well-being. "One of the joys of reading a good essay is watching someone think on the page," says Jerald Walker, author of Street Shadows: A Memoir of Race, Rebellion and Redemption. In The Los Angeles Review of Books, Ned Stuckey-French recently talked about the "shared intimacy" between the essayist and reader being like "a fireside chat between two close friends."

Watching Sanders traverse the trails of tension with his son makes me feel much more human after trying to propel my own son to do pretty much anything he doesn't want to, even though he is much younger than the teenage character. The candor and clarity of Sanders's pursuits in the fresh language of his rhythmic prose, make me want to buy Hunting for Hope for all my friends who are dads.

These books are not just a flashlight in the dark uncertainty of fathering children. They are minds hunting for new ways of seeing the role of dad, the role we execute, at times, with painful human inadequacy. Reading insightful reflections can help us adapt, the way our eyes adjust to the slim light creeping through the blinds at night, which is an ability we can forget we have.