A Conversation with Itzhak Perlman

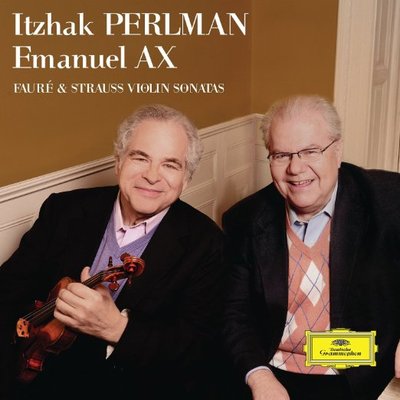

Mike Ragogna: Itzhak, your new album Fauré & Strauss Violin Sonatas is another project recorded with Emanuel Ax, and it's your first album of new material in over a decade. Why did you choose these particular pieces for your return to recording?

Itzhak Perlman: Well, the thing is this, when one plays a recital of their life, there are certain sonatas that you schedule on the recitals. I've been playing recitals for a very long time and a lot of the pieces I've played in the recitals such as Beethoven, Brahms and Mozart I've recorded. There are some that fall by the wayside sometimes and the opportunity of recording them doesn't present itself for no particular reason. Those were the two that I've been playing for a long, long time and I realized, "I've never done that before, why don't I do it?" Sometimes you also look for somebody that you want to play with, and we are very good friends, Manny and myself. One day, I said to him, "Why don't we do this? I've never done that before." It was just that the circumstance did not present itself, and now it did.

MR: Over the last decade, you've kept very busy but you haven't recorded. Was there a reason you took a break?

IP: No, I'd just recorded everything as far as I was concerned. It wasn't a question of taking a break or anything like that. The recording industry is not what it used to be. I wanted to do something that I really wanted to do. When it comes to pieces that you want to do, sometimes record companies say, "Why don't you do Vivaldi's Four Seasons?" "But I've done it twice!" "Well, a third time would also be good!" They think a lot about marketing, even more now because the record industry has changed. We don't call them "records" anymore, we call them "downloads." It's not like you can go to any store and get CDs, those stores are getting scarcer. You can get everything online. So it's changed.

MR: From your perspective, what has that done to classical music?

IP: It's just changed it. The thing is that classical music was always about concerts, about live concerts, and that continues to be true. In order to get the recording of the piece, that's what has changed. Instead of you going to one of the record store chains that used to be everywhere, you now go online. You go online and say, "Let's see, I'd like this piece and that piece...do we have Perlman on that? Oh, we don't? Then we have somebody else and we can get it." So that's basically what's changed, the way that you're exposed to classical music. And in many ways, it's kind of easier. You can just go to Spotify and put in a name and there it is and you can buy the recording through Amazon. You also get the possibility of listening to a recording before you make up your mind on whether you want to purchase it. The only thing that's not as nice is you don't get something to hold on to. You can still do that but it used to be that you could get an LP to play on a record player, and the cover of these recordings was something really very, very serious. There was an art department and they used to come up with all sorts of inventive covers, whether it was a photograph or a landscape or something that involved both, or whatever. Right now, you look at the cover of a CD or a download and it's like a postage stamp! It's very funny, you look at it and say, "Wait a second," and you touch it with your thumbs and try to enlarge it just to see what it really looks like. From that point of view, it has changed.

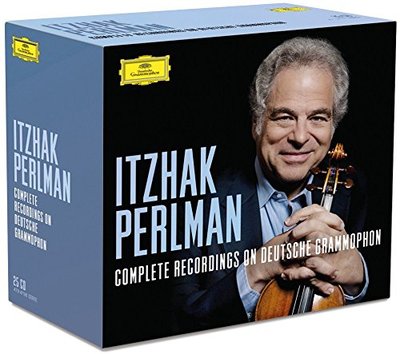

MR: Then there's your new twenty-five CD Deutsche Grammophon box set.

IP: Well, there you can see all of the toil that they put into the covers. Some of them are quite interesting, but right now it's like, "Put my name on there and do a little bit of something and there you go, you've got the cover." But we worked hard on the cover for the Fauré & Strauss. I thought it came out nicely.

MR: Your partner on the project, Emanuel Ax, is someone you've performed with over the years. How has your relationship evolved during that time?

IP: We've been friends for quite a few years and it started out as just being friends because we're in the same field, the music field. We lived not too far from each other and you have a social life where you see people in concerts and so on, so we've known each other since our kids were tiny. Manny's younger than I am, I'm always the old guy. I've grown to admire his playing and so on, so it's a natural thing. We've played a few concerts here and there. We didn't play regularly, but every now and then we would do something together. We know each other's playing, so this was something that was quite natural.

MR: Do each of you bring out certain creative qualities in the other?

IP: You would hope so, yes.

MR: You're celebrating your seventieth birthday on August 31st. There's your new twenty-five CD box set as well as Fauré & Strauss Violin Sonatas. And when you look at your musical history, you've played everywhere from the White House to Sesame Street. Any thoughts on your career or body of work?

IP: You mentioned the twenty-five record set. Well there's another one that has sixty-seven CDs that's also being issued with different records. So there's a lot of stuff. I just got one yesterday, I took it out of the box and it was heavy. [laughs] That's me for the last fifty years It's heavy! But you don't think about it. You say to yourself, "I'm very happy that I'm not upset by what I did before, it was a very good representation of my art and what I did." We were just talking the other day about, "Would I play some of these things today the way I did then?" The answer, of course, is no, because everybody has to evolve artistically. That's one of the things that people ask me, 'What do you see in the future?" In the future, I see continuing to evolve. It's never like I've arrived at something and that's it. You can't do that. You have to continue to move forward, to evolve and look at music slightly differently and so on. Most important is to still be interested in what you're doing. Be interested and be enthusiastic about what you do with your life and your music. In my case, I'm very lucky that I'm able to not just play but also teach and conduct and these three things support each other and give me great pleasure and continued interest.

MR: I normally wait for this question until the end of the interview but you've set it up nicely. Itzhak, what advice do you have for new artists?

IP: If you love what you do, that's number one. You have to like what you do. Let me change your question a little bit, because this is a question that my students ask me: What advice do you give students as they continue their life with music? I keep telling them that they have to be flexible. As long as they love music they can do so many things. It's not just "If I can not play Carnegie Hall I don't want to be in music." Music is one of the luckiest things to have as a profession, because you're dealing with great art. You have a lot of flexibility, like in my case whether I play concerts, which I've been lucky enough to do, or whether your teach, or whether you play chamber music or whether you start a group or whatever it is there are so many opportunities and so many versions of what you can do with your music, so I always say to everybody to be flexible about what you want to do with your life as a musician. I suppose that I could say the same thing for people who are a little bit older. Also, one of the most important things for me as a performer is to always ask questions. "Why am I playing it this way? Am I performing it this way because I'm convinced that this is the way to perform it or am I performing it this way because that's the way I performed it a week or two ago or a month ago or a year ago or five years ago?" Music is constantly moving and evolving. As a performer it's our job to make that music always fresh, always spontaneous. To do it always the same way is not a good idea. Another funny incident that happens after concerts sometimes is people hear you play a concerto and they come backstage and say, "Oh, you played that differently than you did on your recording," and I say, "Thank God for that." When you go to a live concert you have to listen to something that is happening right now. You're not supposed to hear a copy of the CD. The CD is one performance and the live concert is another. It has to be fresh.

MR: My classical pianist friend, Werner Elmker, once told me that the great composers might be horrified if they knew their works were being played purely as written. What's your opinion?

IP: For me, to write everything down is very, very difficult. You can not write down nuances. You can not write down colors. You can not write down phrasing. You can write down as much as you want, there are some composers who try to write down every little bit. Gustav Mahler, for example. If you look at his score it's just full of instructions. You have to do it softly but with energy, or you have to do it loudly and with great intensity. He tried to describe everything exactly how he wanted it to sound but that's very difficult. When you talk about composers such as Beethoven and Mozart and Bach they just wrote things that were relatively limited, like fast or slow or loud or soft or crescendo or diminuendo or whatever, but in the long run the stuff that makes the work sound alive is what the artist does. That's a little bit difficult to put on paper. I suppose your friend is right, some composers would have loved to hear a modern performance of their work. There is a whole thin, I'd don't know if you're aware of it, of playing music "The old way," the early music style of playing which includes a lot of non-vibrato. It sounds kind of weird, to me anyway, but it's a movement that's been there all this time, orchestras who play the original way things were played when those composers were alive. I think those composers would have been absolutely delighted to hear a contemporary performance of their work. Delighted.

MR: Have you evolved any piece to a point that it was far beyond the original vision of the composer?

IP: No. When I listen to recordings that I make of pieces we play, you have the standard work, the Beethoven concerto, the Brahms concerto, and so on and so forth. They evolve in a natural way. It's not like one day it sounds like this and the next it sounds totally different, but there are very subtle differences between what I did thirty years ago and the way I play a piece today. It's not like black and white, it's what I like to call shades.

MR: Have you analyzed your technique through the years? Can you pinpoint some changes in the way you play or that became more refined?

IP: Yes. It's not so much in my playing but it's in my ability to interpret and my ability to listen. That's basically what it is. When you play, technique is technique. You've got to be able to execute everything. You need technique in order to execute things musically, but the difference basically is in my ability to really listen to what I'm doing right now in a particular way so that I can then interpret it in a different way. I think that's what's changed. I don't want to sound elitist or vain, but I suppose when you get old enough you start to listen better. That's what I find at least in my case. I hear something and I hear it in a particular way that I did not hear it before.

MR: Perhaps due to life experience and maturity?

IP: I suppose, yeah.

MR: Now, is your choice of music or interpretation ever a commentary on what's happening in the world?

IP: No. I just listen to what I'm doing and I play a particular piece, but it's not like, "Something horrible is happening and I'm going to do something in that particular way."

MR: Are there any composers you still need to take on in a bigger way than you already have?

IP: No, I'm taking whatever it is that I'm taking. My violinists don't have the width of repertoire that pianists have. Pianists can keep going and going and still not repeat anything. Fiddle players have got a particular repertoire that they do and inevitably they keep repeating it. I've done pretty much what I've wanted to do. If I haven't done something it's because I don't like the piece. I don't believe in doing something because I've got to do it, I believe in doing something because if you can be convinced yourself that you like this particular work then you can give it the kind of interpretation that you feel compelled to do. But sometimes I try something and I say, "Oh, everybody does this but I don't like it, so I'm not going to do it."

MR: What are you going to do? Anything on the schedule beyond these new releases?

IP: No, I'm just doing my regular thing. I'm in the middle of our summer program called the Perlman Music Program, which is a program that my wife started twenty years ago where I teach. Basically all I do in the summer time is teach, and that's very exciting because I deal with young kids, students between the ages of twelve and eighteen. So I do that throughout the year and we have all sorts of plans, a Summer residency in Florida and we go to foreign countries, this year we're going to go to Israel. My life is full of teaching and then of course the conducting that's coming up, I do different orchestras, and occasionally I do different recordings and I do some klezmer. My life is full and I'm very, very happy with what's been going on.

MR: Do you think someone you currently are teaching might be gifted enough to be a major artist, perhaps, well, the next Itzhak Perlman?

IP: [laughs] You never know! The students in our program are on a very, very high level. What happens with career and stuff--I don't want to say it's a craps shoot, but sometimes it's being in the right place. So I don't know. Whenever I listen to somebody play I say to myself, "This person is really amazing and we'll see what happens," but when you talk with kids who are twelve, thirteen, fourteen, there's still a few years where things can go right or things can go wrong. You never know. I always say, "This is a good talent." Then what happens with the talent is a matter of, "We will wait and see." I can't really say anything more about that.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne