Turns out fertility injections really make you want -- your mommy

Part two of two.

"You can't reap your harvest without first planting seeds, right?"

My Chilean fertility doctor thinks farming metaphors can help someone woefully unscientific like me understand the intricacies of ART -- assisted reproductive technology, for the uninitiated.

"Hey, I know where babies come from -- or I used to," I tell him, trying for levity.

In the case of IVF, the doctor's metaphoric seeds are not sperm but high-dose hormones with which I learn to inject myself in the abdomen to make as many egg-dwelling follicles grow as fat as possible, preferably more than 18 millimeters in size. Later, Dr. Q. will retrieve as many eggs as he can -- some follicles will have merged or faded away, as best I understand it -- then he will promptly high-tech-inject them with sperm, which ideally fertilizes almost a carton's worth, or would in a woman under 35. Half a dozen or better in somebody pushing 40, like me, bodes well.

"I'm just kind of scared of all the drugs. They make me feel so dead. Are we being too extreme here?" I ask him.

"We're being as extreme as is necessary."

Working in my favor, or so I think, is the fact that my mom gave unplanned birth to me two months shy of her 40th birthday. I remind Dr. Q of this hopeful point.

"Doesn't mean much, honestly," he says. "You are you; she is herself."

What bodes decidedly darker are the statistics for a female my age with my own particular vitals -- due to a slightly elevated FSH (follicle stimulation hormone, the juice that jumpstarts ovulation), my chances are roughly 30 percent per IVF try -- and the fact that my husband and I can't afford to perform the in vitro procedure ad nauseam, as much lucrative fun as it might sound to Dr. Q.

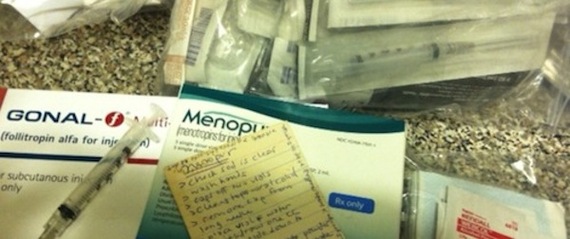

But I want to have a baby -- and Michael's supportive of my desire, if he's not as desperate to achieve the goal. So, I inject the high-powered hormones, which are called stims, for stimulation meds -- branded with sci-fi names like Gonal-f and Menopur -- night after night after night, stretching into 16 nights, longer than the average female patient's stim time because my eggs are "good-looking but slow-growing." I give myself so many injections that the softest part of my stomach starts to resemble a junkie's tattered arms. (As I go, I'm more and more anxious for my nurse to announce my official "trigger day," which is really the night hour when a prepared patient is finally instructed to inject her ovulation-inducing syringe, the last shot in the whole damn cycle.)

As the "stim schedule" progresses -- a name that makes me picture pleasant flower-arranging duties -- I visit my clinic most mornings at eight for blood work to measure my estrogen count and an ultrasound to film a reality show of my plucky, fighting follicles.

"Which ones will emerge the winners?" Dr. Q. asks. "We wait; we see."

Meanwhile, I take prenatal vitamins and eat lots of lean protein and veggies; I cut coffee; I cut wine; I cut soy products; I strive to sleep on my back rather than my stomach; I stop coloring my hair; upon a nurse's advice, I replace my habitual, stress-reducing, five-mile runs with leisurely walks in the park that give me tons of time to think -- about what? Usually how wiped I feel, how much I miss caffeine, then how sore I am, how hot-flashy and constipated and pimply from the meds' recent dosage increase, then how pregnant I think I look with all of these follicles sprouting in my uterus, with my formerly B-size boobs nearly swelling into aching D cups, and then, usually, how much I'd like to be pregnant instead and sore and tired and bloated because of that.

I ask myself: "Do you really want to have a kid this bad? You've waited forever."

I see parents and children exercising, goofing, holding hands and some even arguing nastily with one another -- all around me.

"Yeah, for sure," I answer as before. "I want this chance."

On the way home, I remind myself how all of this endless drug-taking and clinical prodding are my privileged choice, my elected First World problem. This thought is mature. I feel together, momentarily, like my own tough-loving parent, the parent I'd like to become. However, once I'm back inside my house and the sun fades to black, invariably, I crumble and allow myself to consider how much I wish my mother in North Carolina would take the initiative to call me and chat breezily and factually and finally deeply about the whole ART regimen -- to listen -- something she cannot often bring herself to do.

When I told her by phone that I'd decided to pursue IVF, I worried she might disapprove of the scientific intervention factor, the way she criticizes celebs who get plastic surgery: "Meg Ryan was once so wholesome looking; post-surgery, she's a hideous monster." I feared she'd make a crack about a robot baby.

"Do whatever it takes," she said, surprising me.

I recalled how she once advised me in my late twenties, "You're losing eggs even as we speak," indicating she hoped I'd be a mom, and then never, ever broached the subject again.

"I'm apprehensive," I admitted.

"Don't be! No. I hear those treatments are foolproof," she said.

"Not exactly," I said, hoping we could discuss the nitty-gritty for once.

"Oh! What time is it?" she cut me off. "I should let you go, busy girl! And I have to bake a banana bread for the choir party!"

Later, I mentioned the procedure to my hard-of-hearing dad by email. He ignored the reference, but weeks later typed out: "Best of luck with your medical endeavors."

By the time I came along in our family line -- "a wonderful surprise" conceived on a ski trip weekend -- my sister and brother were in high school, and my parents took a loving but laissez-faire approach with me. If I felt "sick," I could camp on the sofa and watch TV for three or four days straight, few questions asked. If I wanted to have a friend sleep over, "Choose someone quiet." My mother worried dutifully about my nutrition and sleep requirements, but she didn't pry into personal matters, like friends or physical changes, beyond telling me my brain deserved harder books than Superfudge.

She occasionally urged an opinion, but rarely set a hard and fast rule. As a child, I actually fantasized I'd get grounded. On the flip side, when I fantasize about motherhood, I imagine impressively consistent structure (fun time; homework time; dinner time; bath and bedtime). I write scripts of intense daily conversation with my son or daughter; I envision an impossibly endearing and enduring best friendship. I pray I can one day say, "You're so grounded, kiddo!" while gunning my thumb and index finger.

Trigger day finally dawns -- a milestone signaling our IVF race's last rigorous heat -- and after dinner it will be time for my kind husband to plunge a dense, intramuscular shot through the circle my nurse has drawn on my right buttock with a Sharpie, the much anticipated injection which will, in 18 hours' time, supposedly bring about my ovulation.

On trigger night, I drink two ounces of Cabernet to relax my speeding mind. I pull down my jeans in the middle of the kitchen and tell Michael, "You can do this, honey."

He hates shots the way some hate blood. But he does it -- does it well. We toast. We wait. I've missed the taste of wine and the floating comfort that comes with it.

At the appointed time the day after next, in coordination with my choreographed ovulation, Michael and I drive to the clinic for the late morning "surgery." He's extra nice to me this morning, carrying my magazines, rubbing my shoulders. At the clinic I am told by a petite nurse to undress and climb into a papery blue hospital gown plus matching cap and booties. As per my written instructions, I am free of makeup, powder, perfume and jewelry, with the exception of my wedding ring, which is officially allowed, seemingly encouraged -- double-income married couples can far better afford IVF.

The room is cold and I wait over an hour in my tiny bed, which is curtained between two other tiny beds occupied by women also waiting to have their eggs retrieved. The woman to my right, Angela, is young and taciturn and alone; the one to my left, Laverne, loud and jovial, and accompanied by her equally loud friend. It occurs to me too late that I could have invited Michael to perch on the end of my child-sized bed instead of sending him off to Starbucks -- I'm glad he escaped this icy purgatory, really.

After Laverne is weighed, she tells the nurse and her surgery buddy that "170 is not as bad as I was expecting!" and I like that she's here beside me. I'm not remotely alone.

And yet again I think of my mother for some primal reason. I imagine that she sneaks through my curtain, her hair in curlers, and cracks an invisible egg on my head -- her famous trick -- tickling her fingers down my hair to create the dripping yolk effect.

It's not that I have felt alone or lonely during this so-called IVF journey -- I do not, have not. I feel as supported as a woman could feel by her spouse, her medical team and her closer friends. I feel lucky. I feel grateful to my mother for refurbishing the lovely antique cradle in which my father was first rocked to sleep in Clarksdale, Mississippi, in 1935. I'm amused when she mails me magazine clippings on extremely obvious points of pregnancy nutrition (don't smoke or drink alcohol) and postcards that feature cats getting into trouble, on which she pens quick messages like, "Imagine how much you love your cats, then imagine how much you'll love a little baby!"

If she can't talk about what I'm going through, she can send quiet signals she cares and even believes against all odds that I will succeed.

When it's time for surgery, another Chilean fellow, Dr. P. this time, tells me, "Nothing's ever gone wrong, so please don't worry," and I tell him, "There's always a first time for everything," as I'm fading to sleep, a sleep better than the biggest glass of wine you could possibly drink.

"Nueve!" says Dr. P. as I wake feeling high and smiley.

"That's good?" I ask.

"Very good," he says. "Now to inject the sperm!"

(He doesn't mean inside me.)

After a day in bed at home, Dr. Q. calls to tell me that six of nine eggs have successfully fertilized. The others have been discarded.

"Is that good?" I ask.

"Very good, sure -- it can be."

"What now?"

He tries on a partial cooking metaphor.

"I will marinate them in a dish over a period of two to five days while they divide and divide and subdivide until they are ready to be transferred inside your uterus where we pray they'll cling to your lining and become a person or, God willing, two!"

"One sounds ideal."

One day later, all of the eggs are dividing well, so it's decided we'll wait for a blastocyst instead of proceeding directly with the transfer the next morning. A blastocyst being an egg that's proven itself an exemplar at division, a luckier bet for sticking to the wall.

By the fifth day after retrieval, my nurse informs me we've still got the winning egg and two other healthy-seeming contestants, while several others are not progressing as speedily as we'd hoped; they'll be left to compete for the chance to survive and become frozen leftovers.

"Three is very good," she adds.

"Are you all right?" Michael asks the night before the embryo transfer procedure. "Can I make you a limeade? Can I measure two ounces of wine?"

"Yes!"

"Can't hurt," he says. "You're currently egg-free. Did you enjoy your run?"

"It was heaven."

"You broke a serious sweat."

When he says that, I remember something long forgotten, how my mother begged me not to run track in high school because she had a theory that I might injure my internal reproductive organs, explicitly my "delicate egg factory," and presumably become infertile. Her nagging/unfounded theory was not something upon which she wanted to expand, only a hunch. I kept running.

When I earned a letter jacket, Mom said, "Isn't this a good reason to stop the torture?"

I finally got it: She didn't believe I might compromise my fertility on the Astroturf; rather, she couldn't watch me complete my long-distance events because I looked frail by the finish. Once in a while, because I'd badgered her into it, she sat in the stands in a sunhat with her hands covering her eyes. She could not witness my pain straight on.

The embryo transfer amounts to nothing more than a menstrual-cramp-like surge when Dr. Q. navigates his stringy catheter through my intentionally full bladder that helps him see more clearly to his ultimate destination, my uterus. Next, the embryos are slid, gently, like highly valuable crystal marbles, through the catheter into the innermost depths of me. Dr. Q's face has never looked so serious, his focus never so acute. I, personally, can't wait to pee.

Still clutched in my left hand, a sentimental white card from the clinic featuring photos of my microscopic embryos makes me want to giggle, an instinct I suppress to avoid wetting myself.

Q's standing between my parted legs when he makes the time to ask me, with my husband looking on, "Are you glad you did this?"

It's the kind of intense question that could take time to answer. Certainly, it's the kind of question I have fantasies of my mother being able to ask me.

"If it works," I tell him.

He winks at me, then immediately turns serious again.

When we get home, there's a dancing kitten postcard from Mom: "Shake it! Don't break it!" reads the caption. The kitten discos on a desk; a ceramic lamp leans sideways.

She's scribbled in her tidy minuscule print: "Imagine how much you love your cats, Betsy, and you'll have one millionth of an idea how much I love you."

The impossibly sweet card makes me sob. It's the built-up exhaustion doing some of the breaking down, but it's also me -- hungry for Mom's words.

That night I call my mother for a brief check-in, as I do after every major medical event, hers or mine, just to confirm all is well -- my father still finds it awkward to discuss anything IVF-related on email.

I tell her I've come through the treatment process now and ask her how she's doing. Obviously, I'd love for her to ask me the same and wait patiently for my response. When I flash on the historic image of her sitting in the bleachers at my track meets, hands shielding her eyes, I try to accept for the thousandth time that she can't.

"That's wonderful," she says about the IVF marathon. "I'm fine -- though that rash is back on my arms. Too many strawberries! I can't stop eating them."

There's a silence. I don't mean to let it last, but I'm not sure what to say. Some stung part of myself can't seem to tell her I'm sorry about the rash.

"Did it hurt when they took the eggs, baby?" Mom ventures to ask.

I feel like I might cry -- just then my dear old cat rubs against my legs.

Without waiting for a response, she quickly adds: "Oh, and Bets... did I tell you about the movie we just saw, The Butler?"

At 80, she sounds like a child to me more and more, even though her mind is fully intact.

For a second, I try to pretend she is my child. I imagine cracking an invisible egg on my mother's curly head, performing it realistically right -- with great care -- like she can.

It occurs to me that if I were her mother, I'd actually answer both her questions.

"No, no, retrieval itself doesn't hurt -- it's something like reverse farming," I say, sounding unmistakably cheerful. "You farm the eggs and then you plant them."

"That's awfully funny," she says. "What modern science can achieve- - Lord."

She clears her throat.

"And, no, you didn't tell me about The Butler," I say. "So how is it?"

"Well, it's such a powerful story..."

"Is Oprah good in it?"

"Oh, yes, she's very believable! Of course, she's gained weight again. Do you have time for this? I know you're always so busy, too busy for silly chitchat!"

"No, I don't have to go tonight- - tell me all about the movie," I say.

And she does, and I close my eyes and listen as carefully as I can.

This essay was originally published at Medium.com.