When it comes to monetary policy, the Federal Reserve has just two jobs, and it's failing at both of them.

The Fed has a dual mandate to promote maximum employment and to keep prices stable. A slate of troubling new economic data released Thursday morning suggested that central bankers are accomplishing neither -- although, to be fair, the clown show in Congress is making their job much harder than it needs to be.

Weekly unemployment claims jumped to 360,000 last week from 328,000 a week earlier, the Labor Department reported. It's an eye-opening jump, although one week's number doesn't necessarily mean much. The four-week moving average of claims, which smooths out weekly fluctuations, edged up less dramatically.

The moving average of new unemployment claims is nearly back to pre-recession levels, but job growth has not kept up: The economy is still 2.6 million jobs shy of its pre-recession peak and 8.7 million jobs shy of "full employment," by one measure. Meanwhile, unemployment has ground down to 7.5 percent, still well above the 6.5 percent that the Fed says is necessary in order to start finally raising its key interest rate from zero.

And that's not the only bad job-market news on Thursday: The Philadelphia Fed said its monthly measure of factory output in the mid-Atlantic region dropped into negative territory in May, and that its employment index tumbled to its lowest level since September 2009.

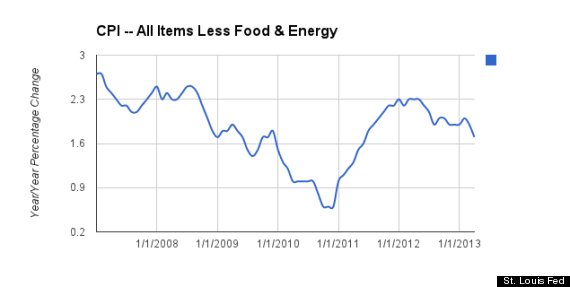

So how about that price stability? Bad news there, too -- though there are many silver linings. The Bureau of Labor Statistics said its measure of consumer prices dropped 0.4 percent in April, the biggest monthly decline since December 2008, the depths of the Great Recession. Consumer prices have risen just 1.1 percent in the past year. Even after stripping out volatile food and energy prices, which economists like to do, prices are still up just 1.7 percent from a year ago, the lowest rate of what's called "core" inflation since mid-2011. (Story continues below chart.)

Now, lower prices are obviously good news for consumers. They help ease the sting of a lousy job market and stagnant wages. The trouble starts, though, when prices fall and keep on falling. Eventually you start to get what's known as deflation, and consumers and businesses put off buying stuff because they start to think prices are going to be lower in the future. This slowly drains the life out of an economy. See Japan for the past 20 years or so.

In its desire to avoid deflation, the Fed has an inflation target of sorts of 2 percent annual growth in core prices. The Fed is failing on that count, too, both by the measure of the consumer price index and by the Fed's preferred measure, the price deflator for core personal spending, which has grown by just 1.1 percent in the past year.

This is why the Fed is still desperately pumping cash into the economy, in the form of rock-bottom interest rates and the extraordinary bond-buying program known as "quantitative easing."

It's a risky approach, and yet it may not be enough to help the economy. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke has openly begged Congress to stop stepping on the economy's tail with its austerity obsession, which has possibly cost the economy more than 2 million jobs. But Congress is still not listening -- and given the ongoing scandal eruption in Washington, the odds of the Fed getting any help are dwindling.