LINCOLN, Ill. ― On board a pair of buses making the nearly three-hour journey to central Illinois from Chicago a week before Christmas, everyone has a number. The passengers are bundles of sleepy children, some accompanied by grandparents, who offer up a “one,” “three,” maybe “four.” The numbers represent the months ― and in some cases years ― since they have seen their mothers at the Logan Correctional Center.

Maria Moon has a number as well, and it’s specific: Three years and four months. That’s how long it’s been since she was at Logan, where she was incarcerated for 13 years.

“I always knew I’d be back,” Moon said. She was confident that her eventual return would be to create a positive change. “From the get go, I knew I’d be back here.”

Moon now works with Cabrini Green Legal Aid, a Chicago group that helped organize the Reunification Ride program for the past year.

The rides help families who otherwise wouldn’t be able to travel to state prisons stay in contact with their loved ones. They have become a way to address the growing population of women, especially mothers, in prison and the need for programs that are more positive than punitive.

Logan reflects this dramatic rise of women in prison, a population that is largely low-income black and Latino inmates, according to a comprehensive report by the Vera Institute of Justice and the Safety and Justice Challenge released this year.

And nearly 80 percent of incarcerated women are mothers.

Yet the budget for programs like the Reunification Ride is slim; in Illinois, a state budget impasse decimated programs that support families caught up in the justice system. The donor-funded Reunification Ride can schedule visits only as funds allow. For now, women’s prisons are the priority because they typically get fewer family visitors than do men’s prisons, where visits are often organized by female relatives, according to Cabrini Green Legal Aid.

And with the paring down of state programs alongside the steadily growing female prisoner population, demand for bus seats is always greater than availability.

At the same time, corrections officials increasingly recognize the value of fostering such family and community contact. Advocates like Moon note the visits help to promote the kind of healthy behaviors and patterns that the women will need to continue outside of prison.

The pre-Christmas visit to Logan is the final one of the year and comes at a time many of the women say they’re reminded most of what they’ve lost and what they hope to regain when they’re released.

John Baldwin, director of the Illinois Department of Corrections, has been encouraged by the Reunification Rides to Logan, especially in the context of the evolving correctional approach to women prisoners.

“Women who have children go back to society in a different way,” Baldwin said. “We’re starting to be in the business of starting to teach life skills and reentry skills to all of our offenders.”

Understanding that women in prison, particularly mothers, have different needs comes amid a broader shift from the one-size-fits-all approach that has failed female prisoners. The corrections system is designed around men, who comprise more than 90 percent of the U.S. prison population.

Georgia Lerner, the executive director of the Women’s Prison Association, a nonprofit advocacy group, said something as innate as the way women communicate can work against them in prison.

“Women tend to ask a lot of questions, which isn’t always valued in the carceral environment,” Lerner said. In men’s prisons, asking questions may signal defiance rather than a need for understanding.

Baldwin noted that this tendency to ask “Why?” is reflected in a higher rate of women being punished more for minor offenses while behind bars.

“For years, the prison system treated everyone exactly alike,” Baldwin said. “We [couldn’t] figure out why we were having uneven success.”

“Women are, in prison terms at least, phenomenally more relational than men. That’s one of the key things the American Correctional Association has noticed in the past 20 years,” Baldwin added. “Women serve time differently than men. A lot of that has do with relationships and family structure and how they came to prison.”

Men and women share several common risk factors for becoming imprisoned, including mental illness, family dysfunction and substance abuse. But even among parents, the factor of what Lerner calls “parental stress” primarily affects women.

“Feeling stressed out that [mothers] can’t care for children’s economic needs, social needs and not feeling competent ― it’s not a criminogenic risk for men the way it is for women,” she said.

“It’s important that we work with those women after their kids leave [the visits] and say, ‘What went right and what went wrong?’” Baldwin said. “We need to strengthen the ways to bring kids to this institution so they can have a positive interaction.”

The women at Logan are sharply aware of how being a mother doubles the stigma they face. While men’s crimes are typically viewed independently of their status as a parent, society views women not only as criminals but also as bad moms.

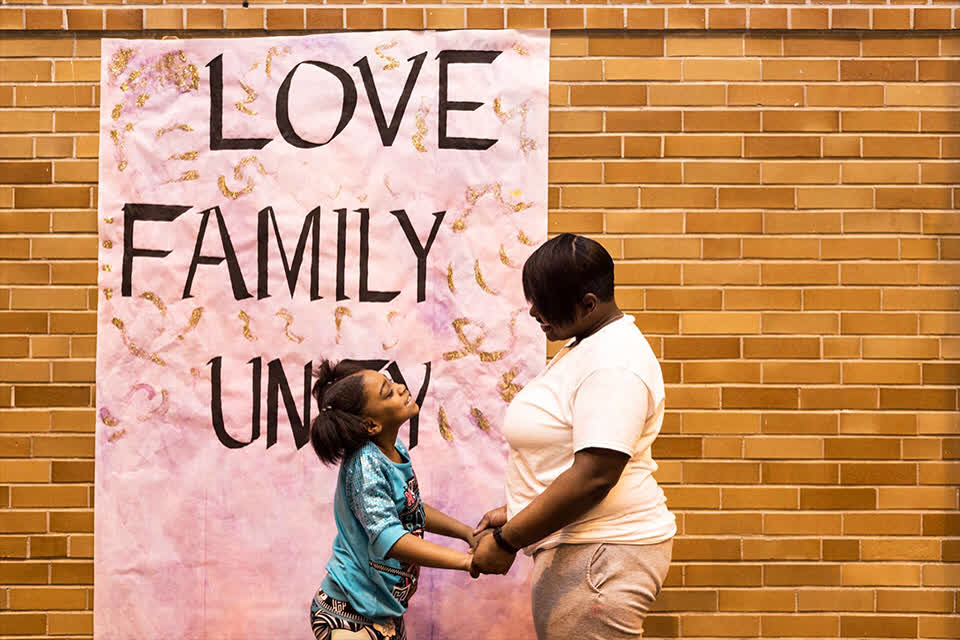

The moms attending the reunion appeared intent on fighting that negative perception.

“When I’m here, it reminds me of what I need to focus on and what I have to go home to,” said Limari Siberon, who was visited by her young son and mother.

As she watched her son color, Siberon held back tears thinking about the time she is missing with her son. “There’s no greater punishment than to be away from your child.”

The December visit to Logan is the closest thing to a family Christmas that the families will have. They’ll pose for pictures with “Auntie Claus,” share a meal, decorate cookies and play games. The moms can’t seem to give enough hugs and kisses as they fuss with their child’s hair or marvel at new braces and extra inches in height.

The children are just as eager for their mom’s affection: Toddlers cling to their mothers and bury faces away from the noisy gymnasium while other children wiggle under their mom’s arm to be closer.

Moon’s visit was a welcome surprise to the women who knew her from her time in Logan.

With her freedom, Moon works to help women who face the same long odds she does. She’s also earning her college degree and raising awareness about the ways communities can help women after prison ― who often struggle with housing, employment and health care because of their incarceration ― make good on their second chance.

She opened her arms to embrace her friends and the children who were visiting from the Reunification Ride. She said seeing her friends both motivated her to keep making good decisions and to keep advocating on their behalf.

She held out her arms to her friend Mishunda Davis, who is still serving her sentence, and called Davis one of her biggest inspirations.

“Just because I’m here and incarcerated [doesn’t] mean that I’m nothing,” Davis said. “I can still teach. I can still encourage. I can still uplift, I can still do positive things getting ready to be released and help others out.”