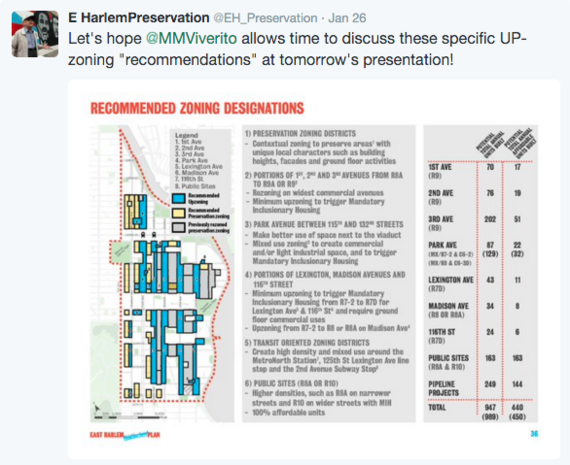

Earlier this month New York city council speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito co-hosted her final community meeting for residents of Spanish Harlem concerned about the city's housing plans. On its face, the meeting, the last in a series that began less than a year ago, would add resident input to the city's hotly-contested affordable housing plan. For months, anger over plans by the city to allow developers to build more lucrative luxury housing in exchange for 'affordable' (a definition itself often contested) units has led to near-unanimous opposition from community boards--including CB11 in Spanish Harlem.

Viverito's meeting, said to engage "hundreds" of residents with snacks and break out groups, produced an "East Harlem Plan" (in just 6 public meetings) that would "inform the final neighborhood rezoning" that will be approved by the Department of City Planning. Facilitated by long-time social justice organization Community Voices Heard (who have otherwise protested de Blasio's public housing proposals), those meetings ultimately embraced the controversial upzonings being pushed by the mayor.

Andrew J. Padilla, a lifelong Spanish Harlem resident and creator of "El Barrio Tours", a documentary project profiling gentrification and displacement in America, has doubts about the process:

"Residents were never asked if they wanted to be upzoned in the first place and told what that would practically mean. They were just told that if they wanted better schools, open space, parks, jobs and affordable housing, that a rezoning was the way they'd get those things.

Rezoning has been described by "East Harlem Plan" facilitators in public meetings as 'neutral'. Upzonings are not neutral."

Padilla points to other city neighborhoods that have been upzoned, like Williamsburg or Central Harlem, which "saw huge swaths of their working class communities of color displaced as property value, tax and rents skyrocketed."

A few days after Viverito's meeting in Spanish Harlem, local immigrant-led group Movimiento Por Justicia En El Barrio hosted dozens of grassroots housing groups and small business owners who came together in their opposition to the city's plans. Speakers called on residents to aggressively reject and resist the city's plan, which Movimiento has described as a "luxury housing plan" that would fuel gentrification and displacement.

Imani Henry helped organize the Brooklyn Anti-gentrification Network, a coalition of grassroots activists and tenants that highlight the intersection of gentrification and policing. Henry says much of the public discourse around public safety in the city, especially as it relates to quality-of-life policing like Broken Windows, is predicated on "what's 'safe' in the minds of gentrifiers." The drastic changes Brooklyn has seen has fueled economic and cultural changes that translate to increased police harassment for people of color.

Parts of Brooklyn now hosting concerts with headliners like Ringo Starr and Josh Grobin are emblematic of a borough transformed. "Now cops are patrolling there," Henry points out. "You live there, shop there but you're being racially profiled because the neighborhood is now catering to white people." Summonsing, an "extra tax on poor people", and ticketing, often directed at dollar cabs (the unsanctioned transportation lifeblood of many of the city's neighborhoods of color), creates an atmosphere of police intimidation that only compounds the stress of rising rents for residents, Henry adds.

Groups like Movimiento and BAN are doing some of the most effective pushing on the ground, scrutinizing the administration and organizing tenants. With rejection of two of de Blasio's key housing proposals, Zoning for Quality and Affordability and Mandatory Inclusionary Housing , community boards would seem to be channeling much of New Yorker's cynicism towards City Hall, too. The mayor dismissed community boards, accusing them of NIMBY-ism and reminding everyone that their votes were only advisory. His plan was above their democratic power, Bloomb--err, de Blasio concluded.

However, community boards, whose members are largely hand-picked by the borough presidents, aren't reliable, Henry says. He describes the community board process, regardless of the opposition to the mayor at the present moment, as a "shitshow". "These people aren't beholden to us," he says. "The community boards are here to deliver the borough to developers... They're doing the bidding of [Eric] Adams." Adams is the Brooklyn borough president and a former police officer who, like the mayor and many city politicians, has taken plenty of money from the real estate lobby.

Alicia Boyd, a Crown Heights resident and the founder of the Movement to Protect the People (MTOPP) has filed lawsuits against Adams and has gone toe to toe with her local community board, confronting board members at public meetings and exposing voting "miscounts". CB9 has responded by calling the cops on Boyd and her supporters, with police escorting Boyd out of a meeting or two. One frustrated CB9 board member has taken to incessantly blogging about her activism.

"There is a lack of accountability and transparency at community boards," Boyd says. Much of the gentrification that's already happened in Brooklyn was blessed by the community boards, she explains. "By the time the community found out about a lot of these deals, the community board has passed it and moved on." Part of the reason Boyd believes that the community boards broke with City Hall on the housing plan is because "so many people are feeling the crunch, they're seeing their neighbors be displaced and they know the culprit is development and politicians." She described the role of the community boards as largely an appendage to "the current political structure" which itself works hand-in-glove with developers.

Clearly there's a danger in letting community boards, politicians and nonprofits (many of whom are funded by the city) assume the mantle of opposition. Having someone like Adams or Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz, who denies gentrification occurs in the Bronx but voted no to zoning changes, steer the conversation is obviously a dead end. Additionally, whatever concessions can be negotiated with the administration (more affordable units, union jobs, etc) wouldn't deviate from the plan's ultimate effects. Meanwhile, housing advocates aren't only fighting the plan but the 'progressive' brand that de Blasio and his allies put forward.

Padilla believes de Blasio is strategically trying make the impression that working-class communities of color are leading the zoning process (i.e. Viverito's meeting), in contrast to the famously autocratic style of former mayor Mike Bloomberg. Peddling a 'progressive' brand (which the mayor promotes nationally) means using buzzwords like ''community plan', 'robust', 'community-driven' and 'affordable housing', Padilla says. This veneer, he explains, "is crucial not only to the passage of these upzonings but to de Blasio and the speaker's credibility as progressive standard bearers beyond this term, beyond this city."

"These upzonings would have a hard time passing if they looked like what they were: the real estate lobby (land owners) forcing working class communities of color to make room for wealthier tenants, raising their property value while displacing our people."

Movimiento por Justicia en El Barrio (photo: Lyssy Pastrana)

Movimiento por Justicia en El Barrio (photo: Lyssy Pastrana)

A speaker talks about gentrification and harassment of Bronx youth (photo: Lyssy Pastrana)

A speaker talks about gentrification and harassment of Bronx youth (photo: Lyssy Pastrana) Boyd and MTOPP at a public hearing in Brooklyn (photo: DNAinfo)

Boyd and MTOPP at a public hearing in Brooklyn (photo: DNAinfo)