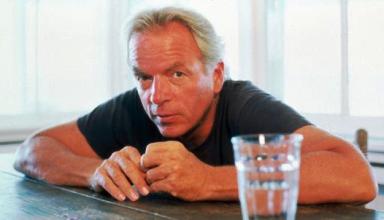

New England WASP Spalding Gray and Jewish New Yorker Woody Allen are cerebral comedians of the highest order. Their content personal, warped yet brilliant, with a skeptical view of the world, both make us laugh and squirm at the same time. But Woody could never commit suicide.

For a year, I'd been keenly anticipating And Everything Is Going Fine. The heavy buzz said the documentary would be the definitive cinematic statement on Spalding Gray. The director, Steven Soderbergh--Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Erin Brockovich, Traffic, Ocean's Eleven, Che--is certainly no lightweight.

Two months ago, at the Sundance Film Festival, my enthusiasm was given a nasty kick. I had also been panting to see Howl, which turned out to be a disaster, a cinematic crime against human intelligence. Howl smothered the word, Allen Ginsberg's famous poem "Howl." With imagery ripping and zipping, and animation flying across the screen and sounds reverberating, the directors Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman did a superb job of swamping content with style (if you want to call it that).

I understand this is the age when imagery dominates: newspapers are closing, the Internet is embracing video, the word as main conveyor of concept and meaning is in heavy retreat. But come on. That the medium can stomp the stuffings out of the word does not mean it should. There are times when the word taking second fiddle screws up the cinematic music.

What filmmakers need to strive for, according to each film, dictated by each film's music, is that perfect union of the word and the image. It's stunning how often Film 101 is forgotten.

After watching Howl devour "Howl," I wondered what would happen to Spalding Gray's train-long monologues. Would his genius be nuked by the flashing of endless quick-pics exploding on the screen? Would the beauty of Spalding's words die an obscene death on a screen of ripping horrors?

After Sundance, I pushed north to the Big Sky Documentary Film Festival in Montana where, to my utter delight, the word came roaring back to prominence -- not Allen Ginsberg's, but Jack Kerouac's in One Fast Move or I'm Gone: Kerouac's Big Sur. Insightful with mad words, lyrical and crude words, words fueled by lucidity and alcoholism, the words stopped my mind from reeling and made my brain focus. That's what words should do. Stop the racing and make you think.

Sure, Curt Worden's film has weaknesses -- inserting popular and sexy talking heads to broaden the audience appeal, a campfire scene resembling Boy Scouts more than the hard-charging Beats -- but the word, the glorious word, pregnant with meaning, was at the center of his film. There was speech without the morbid distraction of flashing imagery. There was Kerouac's voice mostly unfiltered, and seldom overpowered. And in Montana I thought, maybe, just maybe, Spalding does have a chance.

From Big Sky I road-ripped through Wyoming and Nebraska and slid into Columbus, Ohio, for the True/False Film Festival. Whereas Sundance was intensity jacked to the stratosphere with stardom everywhere, and Big Sky had a cozy, relaxed atmosphere with serious documentaries, True/False was collegiate and drunk -- at night, anyway. But I was there for more than drunkenness. I'm no Jack Kerouac.

A few minutes past noon in the Big Ragtime Theater, dark and packed and silent, Spalding Gray, dressed in a conservative suit and sitting behind a wooden desk, appears larger than life. Spalding begins to talk. And for 89 riveting minutes, Spalding does not stop talking.

For five years, director Steven Soderbergh and editor Susan Littenburgh sifted through 120 hours of Spalding Gray film footage, and the product is a mesmerizing hour and half of the master monologist conversing about sex, family, death, and the metaphysics of chaos.

And Everything Is Going Fine reminded me, in a strange way, of Neil Young Trunk Show -- I saw that one at the Woodstock Film Festival (these film festivals are addicting). Filmmakers Steven Soderbergh and Jonathan Demme both understood their films' treasures: Spalding Gray's monologues and Neil Young's music. And both placed their treasures at the forefront. Organize precisely, but keep the end product simple. Let the unmolested, undistracted voices -- the spoken word and the pure music -- capture the audience.

Yet if the word is garbled, moronic, fueled by intoxication, then forget the word. Please! The word has power only when the word is powerful. The same goes for music. Tom DiCillo's When You're Strange: A Film About The Doors made the fatal mistake of giving us the endless ramblings of a stoned and drunk Jim Morrison. Instead of the slurred and shallow, why not present the great music of the Doors and just stay there?

The young Spalding was a troubled boy -- his mother was mentally ill and committed suicide -- and eventually he drifted into experimental theater. From there he moved on to his true calling. Although self-absorbed, his adult monologues are seldom about only himself. They are about Spalding moving through and making contact with others in the world. Although personal, his voice resonates with the public. Spalding's public performances touch us personally. This is because his particular observations are actually about universal experiences.

Spalding called his monologues "poetic journalism." They are poetic, and they are journalism, diving into the confusing human condition and reporting with accuracy and insight. His monologues can also be called performance journalism. At the heart of Spalding's monologues is a meshing of the writer's voice and the artist's voice. It is William Shakespeare and Richard Pryor.

The world is moving on -- Allen Ginsberg is dead, Jack Kerouac is dead, Jim Morrison is dead, Spalding Gray is dead, Neil Young and Woody Allen are old -- but when the word is dead, then filmmaking is too. Yet when you least expect it, the word is alive. In the dark of the Big Ragtime Theater with the bright light of Spalding Gray illuminating the audience, many of them University of Missouri college students, there is laughing and squirming at the same time.