Wiesenfeld as Painter

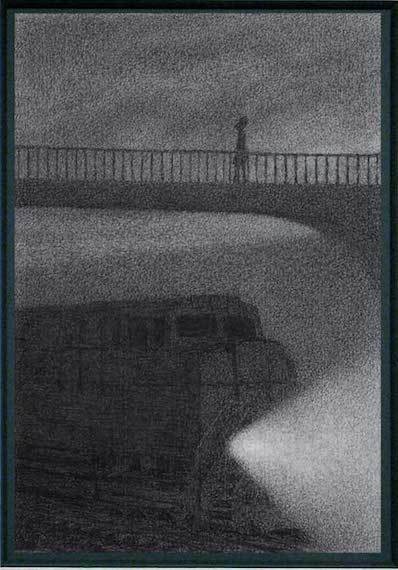

This is The Return, a painting included in Aron Wiesenfeld's show "Solstice" at Arcadia Contemporary.

Let's look at how it's painted. Seen at a distance, or on a computer screen, it produces a nearly dazzling sense of the unification of complex elements. The dull snow under gloomy skies, the transition from snow to slush to pavement, the trees and deep shadows of the woods, the diffuse light on the girl -- all of them read vivid and true.

In person and up close, a jarring second quality emerges in the painting: the edges of the trees are quite sharp, the tire tracks are indicated with bare crude swipes of paint.

Two other instances of this set of painterly quirks leap instantly to my mind. The first is the genre of heroic mid-19th-century American landscape painting. In our conversation, we will let Frederic Edwin Church stand in for all.

This painting, which is on display at the Met, is enormous - nearly ten feet across. It produces a unified impression on a glance, like the Wiesenfeld, and similarly dissolves into totally unconcealed procedural marks when studied up close.

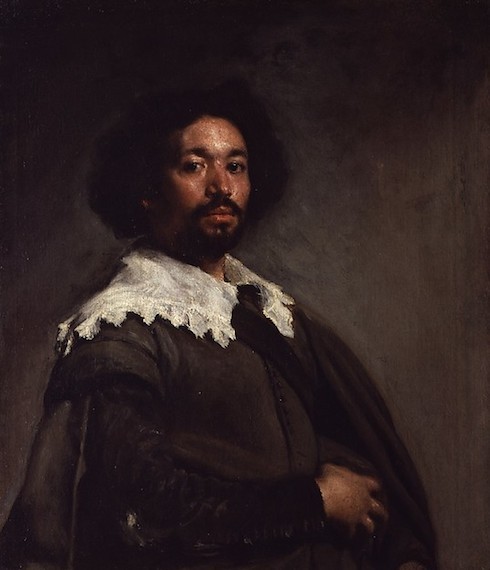

Let's say for a second you're not a painter. What am I talking about here? Well, let's look at a Velázquez.

This painting is intimate in scale, and depicts a single thing - a person. It focuses on the person as a presence in space, and conforms with the optical qualities of a nearby object. The nature of edges is meticulously thought-through over the entire composition. Most are soft, as in the fade of hair to background or shadows on the face; only the edges on the white lace and the black cuff are truly hard. Each brushstroke follows from observation in this painting.

In the Church and the Wiesenfeld, contrarily, the brushstrokes follow from certain formulaic rules of representation. This is not a knock on their procedures. Every priority in painting carries its own costs. Epic panoramas of coordinated color and value require the brushwork we see in Church and Wiesenfeld. Without it, they would take unutterably long to paint, and even if done, the close attention to narrow regions would undercut the overall impression of air, light, and distance.

The other instance of this painterly quirk which leaps to mind is our old friend René Magritte.

Magritte, especially early in his career, stuck a hard edge on every single object he painted. One thinks ordinarily about his images, but when looking closely at the paintings as actual technically constructed works, they are startlingly simple in their execution - paint swiped on with little or no modulation, edges hard, fields of color blank, matte, flat.

Magritte's simple paint application is distantly related to that of Church. For Church, the sensual dimension of brushwork is subsumed and eclipsed in the demands of representing a vision of landscape. For Magritte, the image-idea is so much more important than its execution that he sprints through each painting, trying to finish before any pictures slip from the burgeoning stack he clasps to his chest.

I bring up Church and Magritte because the shocking quality of the edges in Wiesenfeld gives us a key clue to his program. The edges tell us that he did not come here to make a picture. He came here to make a picture of. He is not out to discover his work in the painting. He knows what his work is before he starts; the painting comes afterward. His brushstrokes are not the cause of a picture that emerges on the canvas. They are the effect of a picture that exists in his mind.

Wiesenfeld as Artist

Let's look at another Wiesenfeld.

I have known Wiesenfeld's work for a few years now, and it almost always features elongated, waif-like girls drifting across landscapes that are slightly off - gloomy, or menacing, or displaced in some subtle way.

Just what kind of art is this anyway? To my eye, it descends indirectly from another surrealist - Paul Delvaux.

Like Delvaux, Wiesenfeld peoples strange landscapes with highly stylized women, whom he paints not as psychological individuals, but as repetitive icons of a personal vision of the feminine. There is an unnerving and silent quality to the work of each artist, and each hovers at the very edge, sometimes this side and sometimes that, of good taste.

In fact, Wiesenfeld for me is one of the best artists working in what I think of as the third pole of contemporary art. I divide contemporary Anglosphere art as follows: there is the cool, which includes conceptual art and abstract art. There is the uncool, which includes classical figurative and representational painting. And there is the third pole - a roiling alt universe which includes graffiti, tattoo, and certain hypertechnical outsider genres of fetish, erotic, or horror-oriented painting, drawing, and sculpture. You can find cool art in Artforum, Art in America, and Artnews. You can find uncool art in American Artist, Fine Art Connoisseur, and International Artist. For the third pole, you'll want Juxtapoz and Hi-Fructose (to assert the non-disparagingness of my terminology here, I confess gladly to being primarily a practitioner of the uncool, and proudly to having been in magazines in all three categories).

Mainstream academic art criticism only recognizes the legitimacy of cool art. However, a critical discourse marks uncool art as well - it phrases itself in terms of the long sweep of the art canon, and understands itself as a continuation of millennia of art, with corresponding intellectual and aesthetic responsibilities to bear.

The third pole, however, exists, as much as possible, apart from analytic criticism. It rises from an alienated grass roots, from an unschooled and democratic demand for art. Because it answers to a viewership that does not know or care about theories of unskill, its artists default to that ancient and natural rule of art technique: first be awesome at it. Without awesomeness, a third pole artwork isn't recognizable as third pole. Art nouveau was like this. There is no clumsy, clunky art nouveau, because if it was clumsy or clunky, it wasn't art nouveau.

"Dazzle and enthrall me, be so fantastic as to delight me and so convincing as to turn me on" are the first precepts of the third pole, and, sadly, often its last. It is the pictures painted on the canvas of circus tents. It is pulp paperbacks before English departments get their claws in them. The genre markers it adopts, in order to chase away the dreary critics, choke most of it at an infantile level of unadulterated effect. Like much of surrealism, it is art for teenagers.

And yet it is undeniably awesome.

Additionally, like all of us, it is getting older, and because it is getting older, it is maturing. It is starting to generate artists for whom genre is not the goal, but serves as a scaffold of genre transcendence. I see Wiesenfeld as such a practitioner.

On the one hand, Wiesenfeld partakes of classic third pole shapes in the sky-reflecting patches of water in the muddy foreground road: spiky, nearly fractal, finicky and detailed. And on the other hand, his reduplicated drifting girls become here a haunting crowd of refugees, an endless trickle right to left across a chilly landscape. The tropes of the third pole merge here with abiding human themes, breaking the bounds of their genre provincialism without leaving it behind.

Now, what is third pole art of this sort, that is becoming recognizable to a non-enthusiast as art just as much as it is genre work? Well, it has certain qualities: a very high level of technical proficiency, and an image-driven approach to addressing the human condition. These qualities, however, are identical with the core qualities of uncool art.

The two sectors increasingly speak to one another, as branches of art rooted in representation and humanism. One descends from an unbroken chain of tradition, and the other arises by populist instinct, but they wind up partly converging. At this point, the role of Arcadia comes to the fore. Until recently, Arcadia Fine Arts showed only uncool art: extremely proficient figurative work, primarily in the American neo-Impressionist school which has carried on several techniques linked to John Singer Sargent. Now suddenly they're called Arcadia Contemporary and they're showing Aron Wiesenfeld too.

This change represents a shift in emphasis. Arcadia's curation obviously craves that awesome-at-it quality we have been discussing. Previously, it saw this quality as a function of uncoolness. Now it sees it as a free-standing quality which inhabits various schools of art. I like this change very much. Wiesenfeld has a rare and wonderful imagination, and he creates tantalizing, richly-realized universes full of whimsy, menace, and loneliness. I like that Arcadia has expanded to make room for him.

---

Aron Weisenfeld, "Solstice"

until October 3rd

Arcadia Contemporary, 51 Greene Street, New York, NY 10013

IMAGE SOURCES:

Weisenfeld: Arcadia Contemporary

Church, Velazquez, Delvaux: metmuseum.org

Magritte: moma.org