Renaissance art stripped Jesus, his family and close followers of their Jewish identity. That fact can be easily verified by a tour of any Renaissance art gallery, exhibit, or by examining books that display religious paintings from the Renaissance. You will be greeted in these experiences by images of dedicated first-century orthodox Jews (as clearly described in the Gospels) transformed into Renaissance-era Christians by physical appearance, settings and artifacts. A graphic example is Pietro Perugino's fifteenth-century painting, Baptism of Christ.

The fact that John the Baptist is holding a crucifix as he baptizes Jesus tells the viewer that this is a Christian conversion. The anachronistic presence of other later-day Christian figures emphasizes this baptism as a Christian event. But this image is a falsification of biblical history. It was not a Christian event. Not only was there no Christianity at the time, or even the hint of a new religion, the cross itself was a hated symbol of Roman savagery; it would be another three hundred years before the crucifix would become a devotional Christian object.

Although Christianity did eventually emerge as a separate religion, similar falsifications of biblical history are rampant in collections of Renaissance art spanning hundreds of years. These distortions were not harmless. They imposed a dangerous division between Christians and Jews that lingers today.

Yet, as I learned when I researched my book (Jesus, Jews, and Anti-Semitism in Art: How Renaissance Art Erased Jesus' Jewish Identity and How Today's Artists Are Restoring It) most art historians casually dismiss the idea that ideology was behind the Christianization of Jewish Gospel figures in artworks. In my conversations with several noted experts, they insisted that Renaissance art was driven primarily by technical features and advances in art -- particularly the advent of naturalism and realism and the revival of Greek idealism.

One prominent art historian was adamant that "artists are not interested in history or ideology -- they are only interested in art." I was speechless. What immediately came to mind was Picasso's Guernica, which dramatically represents the horror of war and Diego Rivera's paintings, which expose the exploitation and oppression of workers and the poor. Of course there are many more.

And now, persuasive evidence has emerged that we should put to rest the notion that Renaissance art was not driven by ideology. In her important new book, Dark Mirror: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Jewish Iconography, historian Sara Lipton draws on extensive scholarly research to reveal that pictorial representations of Jews in Christian art, from Medieval times to the Renaissance era, are steeped in ideology. And ideology, she contends, pertains not only to Jews in the anti-Semitic Jewish themes in artworks, but to the general population of Christians as well. For example, she introduces the theme of "watching" -- that in the Inquisitional society everyone is being watched for propriety and piety of behavior.

Lipton illustrates anti-Jewish iconography in her detailed examination of a trove of Medieval and early Renaissance artworks, many of which have slipped into obscurity and were not previously fully understood. In resurrecting these paintings and providing an astute analysis of their ideological content -- political, social and theological -- Lipton provides a valuable missing link that illuminates the emergence of anti-Semitism in artworks. Her book is a must read for anyone who seeks to understand the overlooked ideological underpinnings of anti-Semitism in Jewish iconography in Medieval and Renaissance art.

For the first thousand years after the crucifixion, Lipton notes, Western art showed Old Testament prophets, kings and other Jews, as well as New Testament figures, but no stereotyped physical markers separated Jews and Christians. Then, when Christian artworks proliferated after 1000 CE, images began to distinguish Jews from Christians. Notably, the "Jewish hat," distinguished by a point, appeared, and Jews were also sometimes identified by the presence of a beard.

Professor Lipton asks why Jews were included at all in Christian artworks. The answer, she explains, stems from the close historic connection between Judaism and Christianity. From the outset Christianity had a stormy love-hate relationship with Judaism. Christianity professed its authenticity by claiming it fulfilled numerous Old Testament (Torah) prophesies. Given this close tie to Judaism, Christianity faced a dilemma. How could it separate from its Jewish origins as a distinctly new religion while establishing not only difference from but superiority over Judaism?

A deft sleight of hand accomplished the task, from the Christian perspective. Church leaders proclaimed that Jews were blind to the prophesies of their own scriptures, which, according to Christians, had forecast again and again the coming of the Messiah Jesus. That's why, Lipton says, Jews were included in Christian art "as witnesses" to show their blindness to the divinity of Jesus. The appearance of these Jewish witnesses also confirmed the superiority of Christianity by displaying the defeated lowly status of the scattered and "pathetic" Diaspora Jews -- who were forced to scatter as God's punishment for their blindness. Lipton cites St. Paul, [who many believe was the true founder of Christianity] as introducing the principle of "blindness." She writes that Paul

" ...lamented that his recalcitrant coreligionists clung to the letter rather than the spirit of the law, that the Jews were linked to the material visible world and assumed to possess a purely carnal form of understanding. Their flesh bound thinking, their need for concrete signs rendered them blind to spiritual truths. Even when God himself appeared before their very eyes they could not look beyond the humble body of a crucified convict and see the divine glory enshrined within. Paul blamed this failure on the Jews' overreliance on external symbols and tangible proofs.... He contrasted the Jews' sensory-driven approach to God with the pure faith of Christians."

In the fourth century, Christian theologian St. Augustine picked up Paul's theme, giving it the added twist that the presence of Jews was necessary as witnesses to reinforce the superiority and victory of Christianity. Lipton states St. Augustine's view that:

"the Jews' primary function -- and the reason they should be allowed to remain in Christian lands -- was to serve both as 'witness to' and as 'living signs of' Christian truth and triumph. The Jews did this in several ways. In preserving the ancient Hebrew text of Scripture Jews confirmed the authenticity of biblical prophecies about Christ (although they were blind to their true meaning). The Jews' very bodies...were living proof of the historicity of the crucifixion and their own people's criminal role in it. The Jews' defeat at the hands of the Romans and subsequent dispersal among the 'nations' testified to their own error and to Christian triumph."

The Jewish pointed hat, Lipton notes, was introduced in Medieval paintings, although there is no evidence that Jews wore such hats prior to the thirteenth century, when they were first mandated to wear distinctive hats and patches. Similarly, Jews in eleventh- and early twelfth-century paintings were often pictured with beards, which was also not common among Medieval European Jews.

Both the pointed hat and the beard were artistic inventions for identifying Jews in artworks. Lipton informs us that headwear was commonly used in Medieval paintings to indicate rank or station in life. Popes were pictured with tiaras, kings with crowns and soldiers with helmets. Since Jews had no distinctive headwear to identify them, artists invented the Jewish hat.

Apart from Jews "witnessing" in these paintings, there was no anti-Semitism or demonization of Jews in eleventh and early twelfth century Medieval Christian artworks, Lipton confirms. But that took a sharp turn by mid-twelfth century (1150 CE), when Jews began to be demonized as enemies of Christianity. That was the beginning of Jews becoming, in Lipton's words, "the most powerful and poisonous symbol in all of Christian art."

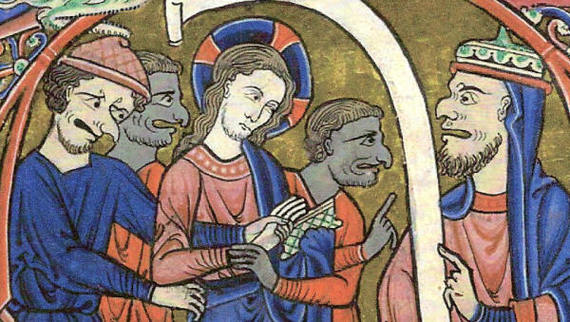

One popular theme showed Jews mocking the crucified Jesus [despite the fact that Jews were the sole followers of Jesus]. In Peter Lombard's 1166 CE Commentary on the Psalms Jews can be identified by hats and noses. The Jewish figure to the left of Jesus is spearing him.

Other depictions, which eventually became stereotypes for Jews, included:

clothing with assigned colors associated in Christian thought with evil, red and yellow in particular, always striped indicative of extravagance. Jewish avarice was indicated by such straightforard signs as coins or bags full of money; or more oblique signs such as ravens or crows, which were thought to hoard shiny objects; or frogs, whose swollen form mimicked the usurer, bloating with greed; or by depicting Jews worshiping idols...The Jews affiliation with the devil might be signaled by placing him in hell, perching a demon on his shoulder, giving him subtly beast-like features, wrapping a snake around his eyes,...and depicting him with a goatee, tail, and/or horns.

And one of the most iconic stereotypes surfaced and took root: the bulbous and hooked nose -- a feature that was not common to actual Medieval European Jews.

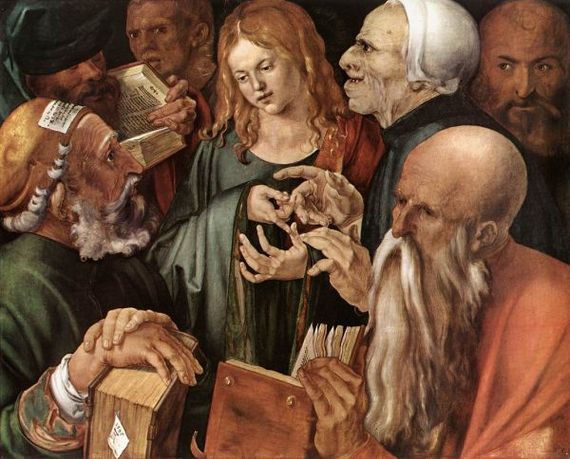

In the high and late Renaissance, as I've noted, the connection between Jesus and Judaism virtually vanishes from artworks. When Jews do appear, as in Albrecht Durer's Christ Among the Doctors, they defy what art historians call the "Renaissance style" of contemporizing figures; in contrast to the "Christian" Jesus, the Jewish scholars (the others) are dark, menacing and ugly.

Explicit anti-Semitic art made a strong resurgence in the eighteenth, nineteen and twentieth centuries, especially in posters and other publications that could be inexpensively produced by printing presses. The Nazi propaganda machine excelled in mass-produced anti-Semitic iconography and literature.

A 2012 exhibit at the Wolfson Museum of Jewish Art in Israel displayed over three hundred pieces of explicit anti-Semitic art -- mostly post-Renaissance to modern times -- from Judaica dealer Peter Ehrenthal's six hundred piece collection. Ehrenthal, a holocaust survivor, was motivated to collect anti-Semitic art to confirm that the anti-Semitic roots of the Holocaust were firmly planted centuries before Hitler's rise to power.

Putting all the pieces together, we can now draw a comprehensive sketch of the evolution of anti-Semitism in art.

Summary of the five stages of anti-Semitism in art from Medieval to modern times:

1-Early Medieval art up to the twelfth-century: no visual distinction between Christians and Jews.

2- 1100-1150: Jews are introduced in Christian art to represent the "blindness" and failure of Judaism and to serve as "witnesses" to the superiority of Christianity.

3- 1150 -- early Renaissance: Demonization, physical distinction of Jews and other stereotypes begin.

4. High and late Renaissance through the seventeenth century: The virtual ethnic cleansing of Judaism in Christian art. Depictions of Jesus, his family, followers and Christianity show no connection to Judaism.

5. Eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries: The resurgence of explicit anti-Semitic art, mostly in the form of printed images and other visual propaganda.

Now that we have overwhelming evidence that iconography in Medieval and Renaissance art was ideologically driven, isn't it time for art historians, curators, teachers and critics to note in their analyses and commentaries the glaring falsifications of biblical history? That might redress long-standing omissions and contribute to healing the historic divide between Christians and Jews by restoring the common ground and heritage of the two faiths.

Bernard Starr, PhD, is Professor Emeritus at the City University of New York (Brooklyn College). His latest book is "Jesus, Jews, and Anti-Semitism in Art: How Renaissance Art Erased Jesus' Jewish Identity and How Today's Artists Are Restoring It." He is also organizer of the art exhibit "Putting Judaism Back in the Picture: Toward Healing the Christian/Jewish Divide."